Tuscaloosa Marine Shale

Early Days Show Promise for the Tuscaloosa Marine Shale

By Gregory DL Morris, Special Correspondent

What pleases independent producers about the Tuscaloosa Marine Shale (TMS) in southeastern Louisiana and the southwestern edge of Mississippi is not so much what the formation is, but rather what it is not. Most importantly, they say, it is not the next Haynesville. Neither is it the next Bakken or Marcellus.

What the TMS is, according to participants in the basin, is a promising oil play where only a few rigs are working–fewer than 20 wells had been drilled in the play by August–and lease rates still were in the low three figures.

To be sure, participants acknowledge, the TMS is in its very early days and there is still a great deal to be learned about stratigraphy, geochemistry and completion techniques. But even the most ardent boosters say they are pleased with a quiet little play they can develop at a comfortable, economical, and technically robust pace.

“We have only three or four rigs running in the TMS today,” reflected Louisiana Oil & Gas Association President Donald Briggs in early August. “When a few people started developing the play, other folks started thinking it was the next Haynesville. Some people still might, but the TMS has very different geology.”

The play is spread over several Louisiana parishes and spills over the state line into a few Mississippi counties. A couple producers are concentrating their efforts on the Magnolia State side of the border, but the bulk of the acreage and activity has been in the Bayou State, Briggs reports.

He says that is good for his state as well as LOGA, but it also has meant some complications. “We have had a bit of trouble with parishes trying to create their own ordinances for different aspects of development,” Briggs says, adding that strikes him, as well as many of his colleagues, as unnecessary on either a practical or regulatory level.

“We have had only 18 wells drilled into the TMS–not per year, but in total,” Briggs says. “Of those, 10 are in production, and we are seeing only about two new wells per parish.”

He contends that is far too few for local officials to be fussing over. Besides, Briggs adds, Louisiana has been a top producing state for close to a century, and has some of the most detailed and extensive development regulations of any state. That means that with the possible exception of highly localized road or quality of life questions, parish regulations usually are unnecessary.

The Big Revelation

Briggs says the Tuscaloosa Marine Shale could be considered Louisiana’s Eagle Ford. In one similarity to that marquee Texas development, he notes that when leasing started in earnest in the TMS about a year ago, it did not take long for 3 million acres to be snapped up.

That is where the similarity ends, however, because lease bonuses were–and continue to be–less than $400 an acre, he says. And even with 3 million acres leased, Briggs noted in early August, “There have been only eight, 640-acre units formed so far in South Louisiana.”

Nevertheless, the flurry of leasing activity drew the attention of legislators and regulators. “People started talking about the TMS, and all of a sudden, (state lawmakers in) Baton Rouge started looking into it, too,” Briggs recalls. “The officials were concerned about congestion and degradation on rural roads, pipeline construction and so forth. But also, everyone in the state knows someone from North Louisiana who became a millionaire from the Haynesville. It was like gold fever.”

Part of the TMS’s slower pace of development, Briggs explains, is because the most prospective parts of the Tuscaloosa are 15,000 feet deep, and the big rigs needed to drill it are expensive and slower to move.

But regardless of depth, early days for a play are just that. “We are still finding the best landing zones and the best cocktails for fracture fluids,” Briggs says. “The first wells have made 300 to 500 barrels a day, but we don’t know how long that will last. Producers still are trying to define the type curve.”

Still, Briggs remains sanguine that the TMS will be a solid play. “People are still leasing, and people are still drilling,” he points out. “Those are the most important things.”

Good Early Results

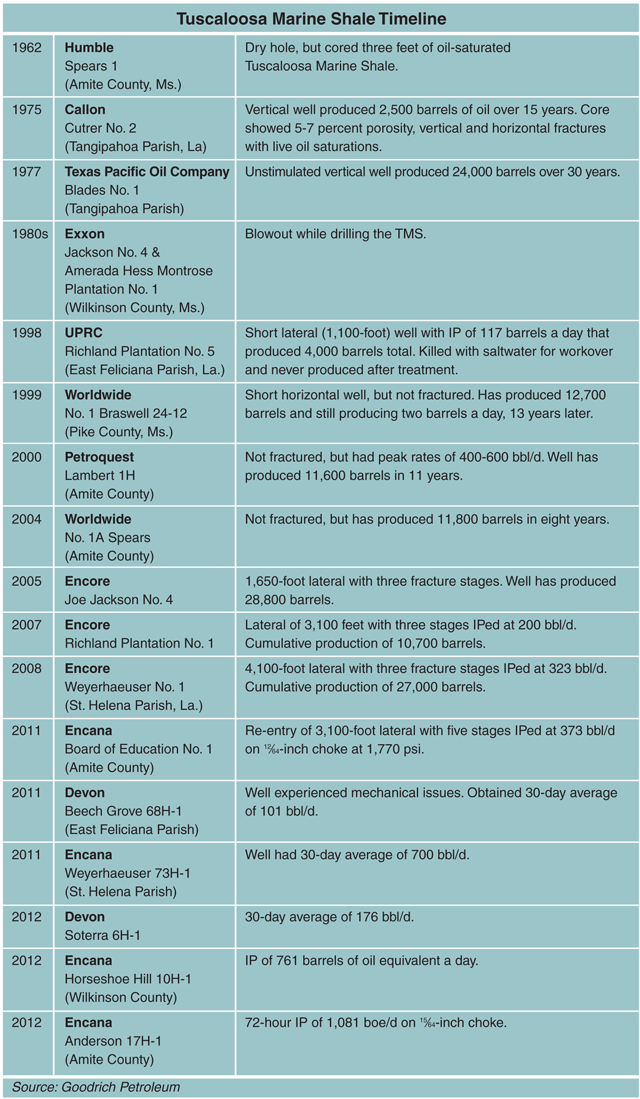

According to Robert Turnham, president of Houston-based Goodrich Petroleum, a signal well for the Tuscaloosa Marine Shale could be the Anderson 17H-1 in Amite County, Ms. The well is being operated by Encana Corporation, and Goodrich has a 5 percent interest. Not only was the initial production more than 1,000 barrels a day, the 30-day average held at slightly less than the IP rate, Turnham says.

He acknowledges that the low leasing rates are at least partially a result of the play’s youth, but he says there also are many unknowns. “There are some negative perceptions about the play,” Turnham states. “It is deeper than most other shale plays, and that means it is more expensive to drill and complete. Also, the initial concern was that the clay content was high, although we no longer are concerned with that. If it is too high in places, proppant can become imbedded.”

More broadly, Turnham adds, “There is a lot we still don’t know, and without a lot of wells drilled, in some cases we are having to rely on old core data. The TMS has something of a checkered past because proper completion techniques were not used. But once this play is proved up, you are going to see things move fast.”

For all its variables, Turnham says the TMS is not without analogies. “We have learned some important lessons from the Haynesville nearby, and from the Eagle Ford, where we have extensive operations,” he says. “Values of the wells and of the acreage are not great now, but in time, you will see those rise.”

And that, in essence, is Goodrich’s value proposition. “We typically move early on plays such as the TMS,” says Turnham. “We take the risk to prove the play. That is exactly what we did in the Haynesville. We came in early and acquired a strong position at only $200 an acre, then we sold a portion of our block to Chesapeake Energy Corp. for $17,500 an acre. If the same thing can happen in the Tuscaloosa, operators who want to get in later are going to have to bid up the value.”

The next steps are being taken already, Turnham reports. “Beyond the first movers taking acreage positions, we are seeing the service companies spreading out. Those are the people who will help us learn how to drill this formation, understand and clearly delineate it. They are the ones who will gain the experience with bits and muds,” he reasons.

Generally, Turnham characterizes the TMS as 150-200 feet thick. “At the upper levels, it is black-gray shale. Lower, it is more brittle, like a layer cake with sand and limestone, along with vertical and horizontal fractures. In that sense, it is something like the Bakken,” he describes. “Technically, the Middle Bakken is not even shale, but a fractured limestone. But upper or lower, it is way too early to be able to differentiate acreage within the TMS.”

Preference For Partnerships

One interesting characteristic of the TMS development so far is that the relatively small number of developing companies report they are quite cooperative, working jointly on wells and sharing data.

As an example, Goodrich has 132,000 acres in the Tuscaloosa Marine Shale and is a partner with Encana on the Mississippi side of the state line. Encana operates the Joe Jackson well, in which it has a 75 percent interest to Goodrich’s 25 percent, Turnham notes. Other wells are different ratios, but Turnham says what really matters is that “we invest the best time and money in the science to get the drilling and completion right.”

He adds that beyond the four wells Goodrich and Encana plan to develop this year, there will be a handful more wells drilled by other companies over the next few months. That pace is expected to continue through at least this year and into 2013. “We and all the other operators are trying to put together plans and budgets,” Turnham says. “We already have some commercial production, but it is too early for us to make reserve estimates.”

Encana has released some information, saying its two Anderson wells hold 730,000 barrels of oil equivalent each. To some degree, the company indicates, the reserve estimates depend on what is found to be the optimum lateral length. Ideas at this point seem to favor 7,300-8,700 feet, as opposed to the 5,000-foot laterals that were used in early wells, Encana reports.

On the technical side, Turnham notes the few producing wells in the play thus far are mostly flowing up the casing. Goodrich and other operators say they prefer to shift that to flowing up tubing to better manage flow back and to allow wells to unload better because of higher pressures. Ultimately, all the wells are expected to go on pump, but when has yet to be determined.

He says the light, sweet TMS crude enjoys some price advantages. “We are getting Louisiana Light Sweet pricing, which is similar to Brent, which has been carrying a $15-$20 uplift over West Texas Intermediate with very little discount for transportation logistics,” Turnham reports.

“There is some infrastructure in the area to move crude north to St. Louis or south to the Gulf Coast, but gas infrastructure will need to be enhanced, once production begins in larger volumes,” he adds.

Another aspect of TMS production is the ratio of liquids. “We are seeing about 94 percent oil,” says Turnham. “That compares very favorably with the Eagle Ford, where we see about 85 percent oil. With prices for the two commodities where they are, the TMS carries a big advantage because of its high percentage of oil. However, it is good to have a little gas to help lift the oil.”

He also says that Tuscaloosa gas is rich, but that the production volumes so far have been too little for natural gas liquids markets to be interested. “It’s just not enough yet to matter,” Turnham notes.

That said, when production does begin to develop, Turnham calculates that producers can anticipate an auxiliary revenue stream from the liquids. But that is in the future. “For now, our goal is to retain 100 percent of our TMS position while we develop and delineate the play,” Turnham outlines. “Down the road, if we sell, it would be a minority interest or a financial partner.”

But the payoff could be huge. He calculates the entire TMS play, at $10,000 an acre, is worth $1.3 billion to Goodrich.

Valuable Position

Kirk Barrell, president of Amelia Resources in Houston, reports thinking along the same lines as Turnham. “We picked up a few leases in the TMS at $175 an acre,” he reveals. “If you look over to what is happening in the Texas Eagle Ford, which is the same formation, Chinese interests are paying $25,000 an acre.”

To this point, however, Barrell notes that Central Louisiana landowners have not reaped great riches. “People seem happy, at present, just to get a check,” he offers. “Typical terms in the TMS are three-years paid, plus a two-year extension. About 80 percent of the leases have a one-fifth royalty, but some of the very early leases have a quarter.”

Amelia was formed in 2003, specifically to develop the TMS in Florida Parish, La. The company acquired seismic and is still evaluating it, with no immediate drilling plans, Barrell says. The firm has leased 60,000 acres in conjunction with one partner and 58,000 acres in conjunction with another. With a third partner, Barrell says, Amelia has a smaller position of just 2,500 acres.

“We hope to have some drilling by the end of the year,” he forecasts. “So far, looking at the seismic, we like the depth and we like the rocks. And patience is a virtue. We may have to wait a bit for the drillers to work their way around to us.”

When Amelia does begin development, Barrell reckons the eastern portion of the Louisiana side of the formation will be the most prospective because that is where resistivity is higher. However, he is quick to underscore that the entire formation is oil-prone, and covers a large area at good thickness, so there is potential all around.

Once more oil starts to flow, Barrell concurs that existing infrastructure will be insufficient. “There are pipelines and roads, but they will be challenged because they are not up to industry standards,” he assesses.

Luckily, he adds, “Both Louisiana and Mississippi are friendly to the industry, so issues from permitting to transportation are likely to be resolved without too much difficulty.”

The only thing Barrell says he does not like about the Tuscaloosa Marine Shale is its name. “As a geologist, I can’t help but think it is terrible nomenclature. I wish I could rename it. Most shales are marine, but the term ‘marine shale’ has become common and accepted.”

Early Movers

Encana was a big, early mover in the TMS, and according to information provided by the company, has 355,000 net acres with an estimated 9.4 billion barrels of oil equivalent in place across 1,250 net well locations. The company says its plan is to establish commerciality through what it calls resource play hub efficiency. That involves optimizing completions and long laterals, as well as an effort to accelerate development through potential liquids joint venture opportunities.

To date, Encana says it has drilled and completed five wells, and notes that with “several industry peers actively delineating the play, data sharing agreements are in place.” The company is running two rigs and says it expects to drill and complete seven wells in the second half of 2012.

Operationally, Encana notes that it is flowing its wells under restricted rates, which maintains completion integrity. It has stated publicly that it has identified operational target zones, and already has eliminated one casing string, drilled and completed an 8,800-foot lateral, and claims to be “rapidly improving drilling performance.”

Figures that EnCana has released estimate costs for future development wells at $12.8 million, with estimated ultimate recoveries of 730,000 barrels equivalent on a 7,500-foot lateral and total vertical depth of 13,000 feet. Over time, EnCana says, it hopes to reduce well costs, drill longer laterals, enhance repeatability, and improve EURs through completion design.

Similarly, Devon Energy Corp. reports it has 190,000 net acres out of a total of 285,000 in its joint venture for the play. The company estimates unrisked reserves at 1.15 billion barrels equivalent for its own acreage, and 1.73 billion barrels for the joint venture. Capital contributions will be $44 million this year out of a total of $167 million allocated for the venture. Devon says it plans to have drilled 10 wells by the end of the year.

Devon says the TMS has several attractive attributes, including a proven capacity to flow oil out of a highly overpressured reservoir. Low-cost acreage, a well-established regulatory environment in both states, and existing infrastructure, also are enticements, according to Devon.

Geologically, Devon states, the TMS shows highly laminated lithology with brittle intervals of sand, siltstone and limestone, and a significant fracture system. The company also notes there are several historical oil pay zones throughout the stratigraphic section.

Devon reports that it has found a widespread shelf setting and low structural relief in a gross thickness of 100-250 feet. It confirms the high resistivity that other producers have noted, and marks the highly overpressured prevailing conditions at greater than 0.7 psi a foot. Samples have indicated fracture barriers above and below pay zones, with fractures present in both cores and image logs. Those fractures are reported to be a dominant component, very dense and closely spaced. They are likely to improve permeability, but will present “challenges for drilling,” according to Devon.

Target well economics for the company are to drill and complete at a cost of $12 million-$14 million in pursuit of per-well EURs of 400,000–600,000 barrels equivalent at 90 percent liquids. First-month IP targets are 1,000-1,200 bbl/d, Devon says. Royalties are reported at an average of 21 percent.

The keys going forward, Devon states, are optimizing drilling and completion techniques and costs, testing longer laterals with 25- to 30-stage hydraulic fractures, and establishing repeatable commercial rates.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.