U.S. Methanol On The Comeback

By Gregory DL Morris, Special Correspondent

As independent producers of natural gas seek to foster markets for their molecules, the bulk of the attention has been focused in only a few areas such as power generation, transportation and possible exports. Petrochemical demand has been on the radar, but primarily as a market for natural gas liquids.

Direct petrochemical demand for methane has been small, but that picture is likely to change soon. North American methanol production is expected to increase 26 percent by 2020, part of a worldwide expansion that is expected to make it a meaningful market for natural gas.

That was established publicly in January when Chesapeake Energy Corp. and Methanex Corporation, the largest supplier of methanol in the world, signed a 10-year contract under which Chesapeake will supply gas to a methanol complex that Methanex is relocating near Geismar, La. The contract has components that link the price of gas to the price of methanol.

“We are excited to support the ongoing revitalization of the U.S. manufacturing sector through our long-term gas supply arrangement with Methanex,” said James C. Johnson, Chesapeake’s senior vice president of marketing, in announcing the agreement. “The unique structure of this transaction provides return certainty and price diversification for Chesapeake, while providing margin protection and price stability for Methanex. Furthermore, Methanex’s investment and plant relocation to Louisiana demonstrates the compounding economic and employment benefits to be derived from the shale gas revolution. We believe this is truly a ‘win/win’ arrangement for both companies.”

Another developer has moved even further upstream in its natural gas feedstock strategy. Houston-based G2X Energy is constructing a methanol plant in Pampa, Tx., northeast of Amarillo, and is evaluating a methanol-to-gasoline plant at Lake Charles, La. Timothy Vail, president and chief executive officer, says the Pampa plant will be supplied by a nearby Kinder Morgan pipeline, and that feedstock likely will be sourced through G2X ownership of natural gas production.

Downstream Collaboration

Taken together, industry analysts and consultants say the Chesapeake-Methanex contract, and the gas well stake taken by G2X, represent savvy and effective new ways for gas producers to collaborate with a growing downstream market.

"Gas-intensive consumers have said they are going to spend $85 billion-$90 billion developing new facilities over the next three to five years. There is a funding gap on the horizon for drilling, so it all comes back to the buyers of the commodity.”

TERI VISWANATH

Director of Commodity Strategy, BNP Paribas Corporate & Investment Banking

“If you look at the deal Chesapeake made with Methanex, and also the $1.02-billion deal in the Mississippian Lime that Chesapeake announced in late February to sell Sinopec at 50 percent interest in its 850,000-acre leasehold in northern Oklahoma, the story becomes very compelling,” says Teri Viswanath, director of commodity strategy at BNP Paribas Corporate & Investment Banking.

“Large independent natural gas producers have been good at using the first-mover advantage get capital to support their development in return for acres,” she explains. “That is how they have been able to support their drilling over the past five years. But the integrated majors have bought their way back into North America, and several national oil companies also have established operations, so those deals are not available as much anymore. If there is not a lot of joint venture capital out there for independents, how are they going to fund their operations? Clearly, they are looking downstream to the consumers of their commodity. That also means the consumer has a different role at the table.”

At the strategic level, Viswanath says, there has been a general reluctance toward vertical integration by corporate boards of directors. But in cases where commodity companies can benefit from such integration to manage their own price or supply risks, “virtual integration” through strategic business partnerships that align financial goals can achieve similar ends. She notes that both the Chesapeake-Methanex contract and the G2X stakes in gas wells are prime examples of that.

“Chesapeake has taken on some of Methanex’s price risk, but with strong rising global demand for methanol, that seems like a good swap,” assesses Viswanath. “Deals like this will be more likely down the road as gas suppliers seek to monetize their resources and also seek development capital. Large, gas-intensive consumers have said they are going to spend $85 billion-$90 billion on developing facilities over the next three to five years. There is a funding gap on the horizon for drilling, so it all comes back to the buyers of the commodity.”

New Cost Curves

The deal with Chesapeake was an easy decision, observes John Floren, president and chief executive officer of Methanex. “We have had methanol production in North America going back 25 years,” he reveals. “In the late 1990s and through most of the 2000s, given the price and supply outlook for domestic natural gas, it no longer made sense to manufacture methanol in North America. We, along with most other producers, idled a large percentage of our U.S. methanol capacity. But as the shale phenomenon took off, we took a new look at the cost curves.”

“In the late 1990s and through most of the 2000s, given the price and supply outlook for domestic natural gas, it no longer made sense to manufacture methanol in North America. We, along with most other producers, idled a large percentage of our U.S. methanol capacity. But as the shale phenomenon took off, we took a new look at the cost curves."

JOHN FLOREN

President and CEO, Methanex

Methanex is not building a “green field plant,” but is dismantling a production train in Chile and reassembling it near Geismar, which is located in Ascension Parish, La., about 60 miles north of New Orleans. Floren says the all-in cost of the project is $550 million, versus $800 million for a new facility.

Preparation at the southern Louisiana site is already under way, and reassembly is slated to begin in August, according to Floren. At the same time, he says, the company expects to make a final decision soon on potentially relocating a second plant from Chile to Geismar. The first unit will make 1 million metric tons a year of methanol when it comes on stream in late 2014. If the decision to relocate is made, the second train could be in service in early 2016.

Underscoring the new role that big customers have at the table, Floren says, “We canvassed the natural gas market, looking at many potential suppliers to the Geismar plant over many months. In the end, we selected Chesapeake. It is the second-largest producer in North America, so our consumption will represent only about 5 percent of its overall volume. That means security of supply for us. Chesapeake saw us as a way to get closer to an oil-based price for its natural gas production.”

Methanex also has a plant producing 500,000 metric tons a year at Medicine Hat, Alberta, which Floren says will be expanded by 100,000 metric tons a year by the third quarter of this year. He says the methane supply for that plant will be bought on a spot basis.

“The United States still imports some gas from Canada, but we expect that will go to zero in the next few years as more domestic production comes on, so we feel the Canadian market will become even more stranded. We will buy spot and forward strips, ” he comments.

While traditional derivatives such as acetic acid and formaldehyde account for about two-thirds of total methanol demand, energy is what is driving global growth, according to Floren.

“There are six ways to get methanol into the energy market,” he states. “The first is as methyl tertiary-butyl ether, which was a major octane booster in the United States until regulations changed. The United States is still the world’s major MTBE producer, but it is all for export.

“Methanol also can be blended directly into gasoline, and that is growing worldwide,” Floren continues. “About 15 percent of biodiesel is already methanol. A fourth way is as dimethyl ether, which is a clean and economical replacement for propane.

“Two of the newest markets for methanol are as a replacement for naphtha in the olefins value chain, and there are just starting to be some ships built in the Baltic that will be able to use methanol or bunker fuel,” he adds.

Natural Gas Conversion

Houston-based Southern Chemical Corp. is another major methanol player. It has production of its own, and sells the output of several outside companies. It is majority owned by the Proman Group headquartered in Switzerland, which is also a significant investor in G2X. Southern Chemical will market the methanol from Pampa, and Tim Vail, president and chief executive of G2X, says the production is completely sold.

“We are fully funded, have all permits in hand, and construction started in February,” Vail reports. “The plant will come on stream late in the second quarter of next year. We chose to build in the Texas Panhandle because Southern already had methanol demand there.”

Vail explains that while the Pampa plant will be an important regional supplier of methanol, strategically, his company is in the natural gas “conversion” business.

“At Pampa, the end product is methanol. Lake Charles will be a larger facility converting natural gas to gasoline, by way of methanol. We are building right off the main ship channel. The plant will make 12,500 barrels a day of gasoline using proven technology to synthesize methanol, then an ExxonMobil process to convert methanol to gasoline,” he relates. “The fuel will be delivered by barge, ship and pipeline to domestic and international customers.”

With the gas supplies secured for Pampa, Vail notes that his firm still is working on methane supply for Lake Charles. “We are working with several natural gas producers. They see this as an opportunity to create new demand for natural gas,” he remarks.

He says he believes the divergence of natural gas and oil prices is durable. “Gas producers are looking for opportunities to move their gas into markets linked to oil. That is why we selected the ExxonMobil technology. It is highly selective to the production of gasoline. We will be getting about 90 percent gasoline that is an 87-octane automotive fuel that can be dropped into the supply chain,” he details.

According to Vail, the domestic market for gasoline is 9 million barrels a day. And while it has been reported widely that motor gasoline demand has been flat or even declining slightly, it remains a large and lucrative market, especially given the price advantages of natural gas.

“We are at a transformative moment,” Vail declares. “We have vast amounts of natural gas in this country–more than we ever dreamed of. And even the boom we are seeing now is only the beginning. There are other zones and other depths, and better recovery. This is the time to be moving natural gas into the transportation sector. There are huge opportunities, and it has been great working with independent gas producers to bridge the gap between local natural gas markets and global liquid transportation fuels markets.”

Monetizing Methane

Global methanol market figures take a little parsing, says Marc Laughlin, associate director for syngas chemicals at IHS. “Worldwide demand in 2012 was 61 million metric tons, which is only 64 percent of nameplate installed capacity. But a significant portion of that nominal capacity is not actively in production,” he notes. “There is one tranche of capacity–mostly modern, larger plants–that operates close to 90 percent capacity, and another tranche of older and less-reliable units. There are also some swing plants that can make methanol or ammonia.”

By 2020, an additional 65.9 million metric tons a year of capacity is expected to be added, but again, the top-line number does not tell the whole story, according to Laughlin.

“A lot of that new capacity is coming in China, where it is being used as a precursor for olefins. There is a three-to-one ratio, so a world-scale ethylene plant producing 600,000 metric tons a year needs 1.8 million metric tons of methanol,” he comments.

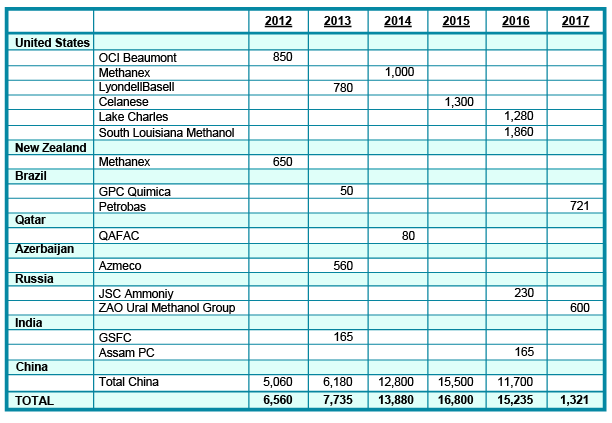

North American installed capacity is 1.8 million metric tons a year, and is slated to grow by nearly 1.0 million metric tons a year (26 percent) over the next seven years, with a total of 6.5 million metric tons of capacity expected to be on line by 2020, Laughlin details. “That is not a big share of global production, but it is a significant improvement from the low point of North American methanol production, which got as low as 1.0 million metric tons a year,” he points out.

Laughlin and his colleague, Mike Nash, global business director for syngas chemicals based in London, concur with other sources who say methanol is a good way to monetize natural gas. “Some of the expansions in North America are back integrations by companies with derivative business; the rest is monetization,” Nash remarks. “North America imports 5 million metric tons of methanol a year, and the new capacity is going to displace some of those volumes.”

Nash and Laughlin note that the North American market, where derivative demand is growing at only about 2 percent annually, must be seen in the wider global context. International methanol demand into the energy complex is growing at several times that rate. “There is demand for methanol, and the new capacity will stimulate more demand,” says Laughlin. “Natural gas producers are happy to supply the fuels market because the end product is priced not at raw material and manufacturing costs, but against oil. Methanol is a perfectly good blendstock.”

Looking at the Chesapeake contract with Methanex, Nash notes that Methanex has similar profit-sharing arrangements for its huge complex of plants in Trinidad. Southern Chemical also has Trinidadian production. “Yes, Chesapeake has taken on some methanol exposure, but if you look at methanol profitability over the long term, that is not a bad model,” he reasons. “It could be quite lucrative for Chesapeake. It is shared risk, but it is also shared gain.”

Laughlin adds, “Methanol is a global commodity that is relatively easy to handle and store. About 60 percent of global production ends up on a ship. The worldwide logistics are very efficient, and there is a strong demand pull on a global basis. We see an upward cycle for methanol for at least the next four to five years.”

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.