LNG Exports

Diverse And Abundant U.S. Natural Gas Supplies To Feed LNG Export Facilities

By E. Russell “Rusty” Braziel

HOUSTON–Natural gas demand is increasing in the power generation, industrial and residential/commercial space heating sectors, but few factors will have a greater effect on future U.S. natural gas production–or pricing–levels than the degree to which U.S. liquefied natural gas exporters can successfully penetrate Asian, European and other global gas markets.

In 2014, the equivalent of more than 30 billion cubic feet a day of natural gas was shipped in the form of 240 million metric tons of LNG per annum (MTPA) from liquefaction centers in countries such as Qatar, Malaysia and Australia to importing nations led by Japan, South Korea, China and India. Once expected to join the list of largest LNG importers, the United States instead is poised to become one of the top three exporters over the next three to five years, and may emerge as the world’s top LNG exporter by 2025.

The first four LNG export terminals scheduled to commence operations are Cheniere Energy’s six-train Sabine Pass plant in Cameron Parish, La., the Cameron three-train project at Hackberry, La., Freeport LNG’s two-train facility at Freeport, Tx., and Dominion’s single-train Cove Point project at Lusby, Md. Cheniere is expected to start up the first train at Sabine Pass later this year, with the other 11 liquefaction trains coming online between 2018 and 2020.

Together, the 12 trains at these four export terminals will have the capacity to supercool up to 7 Bcf/d of gas into LNG and export up to 54 million MTPA (equal to 22.5 percent of the total amount of LNG shipped around the world in 2014).

All four of these multibillion-dollar liquefaction/export terminals previously were LNG import facilities developed before the shale era. Consequently, most of the dock facilities and other infrastructure is already in place, providing a capital-cost edge that enables the projects to offer attractively low liquefaction tolling fees and to reach long-term deals with international off-takers.

All four also have solid financial foundations. Most of the LNG buyers are obligated under the terms of take-or-pay contracts to compensate project developers for the capacities they hold under contract, even if buyers do not use those capacities. The degree to which liquefaction/export capacities are used will depend, in part, on provisions in the export contracts and on how competitive U.S.-sourced LNG will be on the international market.

In addition to the four projects converted from previous LNG landing facilities, even more “green field” LNG export capacity is in various stages of construction and permitting. For example, Cheniere Energy’s Corpus Christi, Tx., facility is scheduled for startup by early 2019. With five planned trains, Corpus Christi ultimately will require 3.2 Bcf/d of gas supply (22.5 MTPA total capacity). The six planned liquefaction trains at Cheniere’s Sabine Pass will demand nearly 4.0 Bcf/d (27 MTPA total capacity), beginning with 650 million cubic feet a day for the first train. When operating at full capacity, these two plants alone represent a demand load equal to roughly 10 percent of current daily U.S. gas production.

Despite a pullback in drilling activity and lower prices in recent years, lower-48 U.S. gas production (after extraction of natural gas liquids) is averaging about 73 Bcf/d–45 percent higher than 10 years ago–and there is no reason production could not continue to grow to supply LNG export facilities.

International LNG Market

The international LNG market has experienced dramatic change in recent years. LNG demand spiked in Japan, already the world’s largest LNG consumer, in the aftermath of the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster. By early 2014, Japanese and other Asian buyers were paying more than $18 an MMBtu for LNG, partly because long-term supply deals were indexed to then-high crude oil prices and partly because LNG demand was outstripping supply.

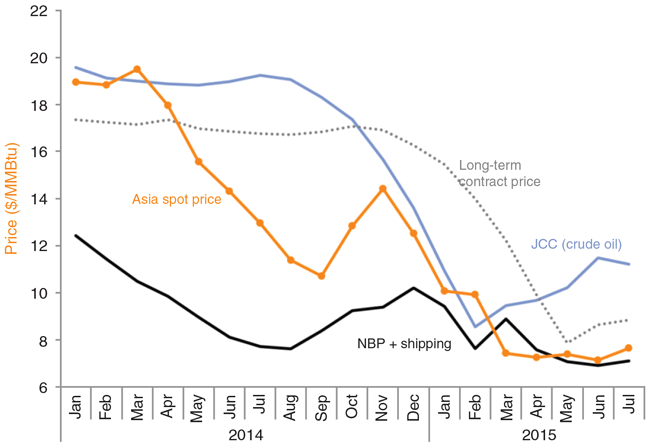

However, Asian demand began to sag in late 2014 as a result of high LNG prices, mild weather, Korean nuclear unit startups, declining oil prices, and new supply from the startup of new liquefaction export projects in Papau New Guinea and Australia (Figure 1). Suddenly, it became a buyer’s market, with spot prices dropping to less than $8/MMBtu.

Even before that price decline, U.S. developers building the first round of lower-48 liquefaction/export facilities had already rattled the international LNG market. Among other things, they linked their LNG prices to relatively low-cost U.S. natural gas and not to global crude oil prices, as had been the LNG industry’s practice for decades. Moreover, in many cases, unlike most international LNG deals, U.S. exporters give buyers the “destination flexibility” to ship LNG anywhere they want, and not only to specific ports.

Thanks to the soon-to-be-expanded Panama Canal, the United States is well-positioned on the map to serve both Asia and Europe. Moreover, liquefaction fees at U.S. plants generally are less than other facilities around the world because of the projects’ lower development costs.

These factors would seem to give the United States a leg up in the competition for LNG, but other factors are at play. For one, at today’s oil prices, LNG prices indexed to oil are certainly more competitive with Henry Hub-indexed LNG prices. For another, the 2014-15 lull in LNG demand growth continues, even as a long list of mostly U.S. and Australian LNG export projects are poised to begin operation.

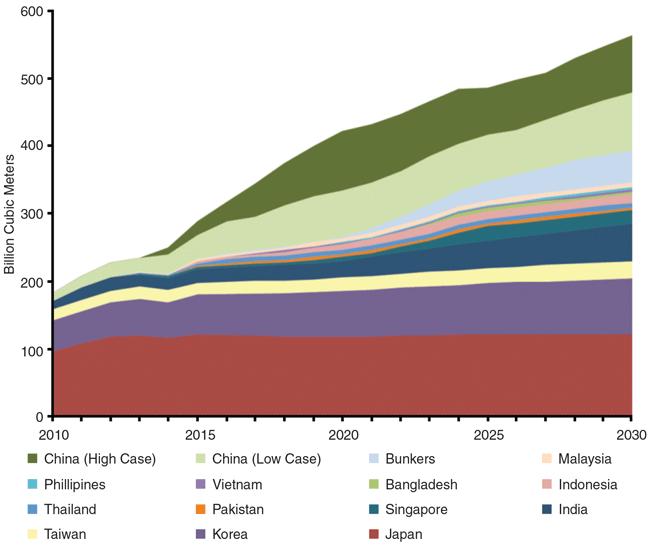

That said, however, long-term LNG demand is expected to rise at an annual rate of 5 percent or more, with most of the growth coming in Asia (Figure 2). In time, it is likely that growing demand will absorb all the new liquefaction export capacity coming on line over the next five years, and could lead to the development of additional North American projects (including some on the U.S. West Coast and in British Columbia).

Certainly, in an increasingly liquid, competitive and lower-margin market, that the most successful natural gas producers and LNG exporters will be those that offer ample gas supplies, low-cost gas production, supportive pipeline infrastructure, competitive liquefaction costs, easy access to multiple markets, and destination flexibility. The U.S. production and liquefaction/export sectors appear to offer these benefits, as well as the bonus of LNG prices tied to U.S. natural gas.

The prospects for U.S. gas producers/LNG exporters appear to stack up well against both Qatar (the biggest existing player in LNG supply) and Australia (which, along with the United States, is the other big up-and-comer). As always in a highly competitive market, success will depend to a significant degree on who is more savvy, responsive and innovative.

New Demand Epicenters

LNG export terminals could well become the epicenters of U.S. gas demand. But how will export facilities manage the challenges associated with securing and moving the huge volumes of gas required to supply the liquefaction trains already under construction?

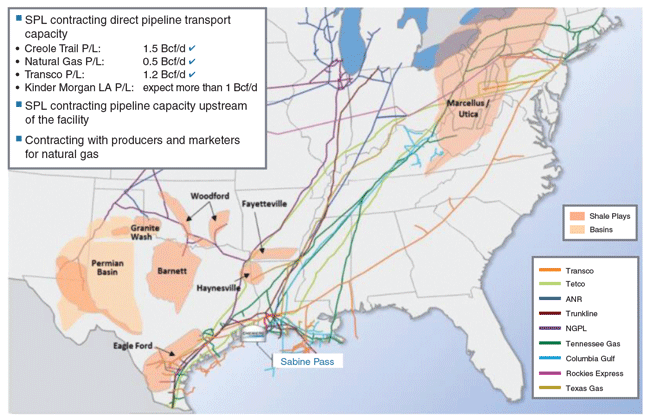

Consider, for example, Cheniere Energy’s Sabine Pass and Corpus Christi facilities. Securing a combined 7.2 Bcf/d and lining up all the interstate and intrastate pipeline capacity to transport that much gas is a monumental logistical task. A key aspect of the company’s supply strategy is diversifying gas sources to include basins hundreds of miles away from the LNG facilities, but that obviously further complicates transportation logistics.

For Sabine Pass, the plan is to source a considerable portion of supply from the Marcellus and Utica shale plays (Figure 3). That feat is made possible by making several big interstate pipelines between the Northeast/Midwest and the Gulf Coast “bi-directional” (these pipelines were designed to move gas from the Gulf Coast to the Northeast and Midwest, not vice versa), and by enhancing the local pipeline networks near the LNG terminals. Cheniere’s thinking, of course, is that getting the best gas price requires competition, and to ensure competition, pipeline capacity is needed to move gas to Sabine Pass and Corpus Christi from a range of sources.

Cheniere has identified several key upstream pipeline expansion projects that will enable delivery of most of the gas needed at Sabine Pass. They include Texas Gas Transmission (owned by Boardwalk Pipeline Partners), whose Ohio-Louisiana Access Project (OLAP) will add bi-directionality to the 690-mile section of the Texas Gas pipeline between southwestern Ohio (Lebanon) and southern Louisiana (CTPL Gillis at the northern end of the existing Creole Trail Pipeline), thereby allowing Marcellus and Utica gas to flow south.

Sabine Pass LNG itself is the anchor tenant on the project, with 300 MMcf/d of firm transportation for a term of 10 years. Marcellus/Utica producer Rex Energy has separately lined up 100 MMcf/d of firm capacity on OLAP for 20 years, also with LNG exports in mind, while Utica producer Gulfport Energy has lined up another 50 MMcf/d.

Four pipelines will move the Sabine Pass-bound gas the last few miles to the terminal: Cheniere’s newly bidirectional Creole Trail Pipeline, Kinder Morgan’s already bi-directional Natural Gas Pipeline, Williams’s planned Gulf Trace project (which is making its Transco mainline and Southwest Louisiana lateral pipeline bidirectional), and Kinder Morgan’s Louisiana Pipeline.

Supply Diversity

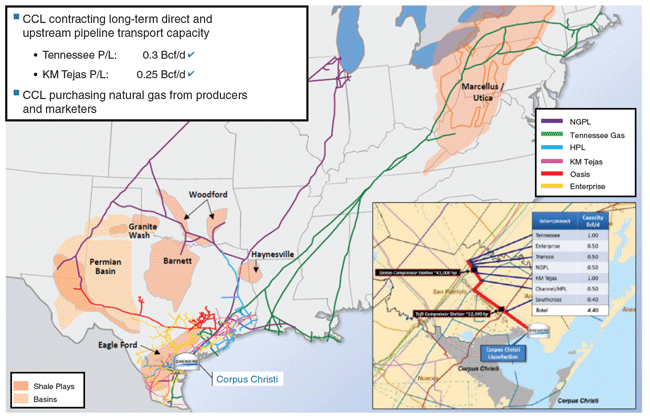

Although the Corpus Christi facility is only a short drive from the heart of the Eagle Ford Shale play, as with Sabine Pass, Cheniere is seeking to access gas from a wide variety of plays and basins–in some cases, moving gas long distances. Also, as it has done at Sabine Pass, Cheniere is looking for both supply-basin and supplier diversity, and plans to enter term supply contracts with producers ranging from one to seven years. The company expects to have initial gas contracts in place by 2016.

One thing that makes Corpus Christi a great place for liquefying gas and exporting LNG is its proximity to several major gas pipelines. In fact, a single 23-mile, 48-inch diameter pipeline Cheniere is building to serve the plant’s first three liquefaction trains will connect with seven regional pipelines with a total capacity of 4.4 Bcf/d (Figure 4).

The 48-inch Corpus Christi pipeline (CCPL) will have the capacity to move up to 2.25 Bcf/d, and a parallel 42-inch-diameter, 1.5 Bcf/d pipeline is planned to supply the fourth and fifth trains. The CCPL will tie the facility into:

- Kinder Morgan’s Natural Gas pipeline (shown in purple in Figure 4), which will be able to deliver gas from the Marcellus and Utica through the increasingly bidirectional Rockies Express system, the Permian Basin, Granite Wash, Barnett Shale, Woodford Shale and Haynesville Shale;

- Kinder Morgan’s Tennessee pipeline (green in Figure 4), parts of which extend to the Marcellus and into the Gulf of Mexico;

- Kinder Morgan’s KM Tejas pipeline (pink), which moves gas produced in the Eagle Ford and the Gulf;

- Energy Transfer Partners’ Houston Pipeline System (blue), which gathers and transports gas produced in several parts of Texas and ties in with the company’s 52 Bcf Bammel gas storage facility near the Houston Ship Channel, as well as Energy Transfer Partners’ Oasis pipeline (red), which connects the Waha and Katy gas hubs;

- Enterprise Products Partners’ Texas pipeline;

- Williams’ Transcontinental (Transco) pipeline; and

- Southcross Energy’s South Texas system.

As of July, Cheniere had lined up 550 MMcf/d of long-term pipeline capacity to service the CCPL: 300 MMcf/d on the Tennessee Gas line and 250 MMcf/d on KM Tejas. That 550 MMcf/d accounts for much of what Cheniere will need to supply the first train (the terminal’s total need is represented by the orange line). The company has an option for another 250 MMcf/d of capacity on KM Tejas to meet the first train’s remaining needs, and is in discussions with the owners of two other pipelines for a total of 785 MMcf/d of capacity to supply the second and third trains.

The financial requirements for getting projects built appear to be easing, or at least becoming more flexible, which could be good news for the possible development of additional U.S. LNG export facilities. For Sabine Pass, Cheniere satisfied lenders with a plan to line up 20-year sales and purchase agreements (SPAs) totaling 21.25 MTPA (79 percent of the 27 MTPA total capacity). It already has signed SPAs totaling 19.8 MTPA. The 21 percent of capacity (5.75 MTPA) will be tied to shorter-term deals and spot market sales.

The Corpus Christi project is satisfying lenders by lining up 20-year SPAs for only 10.5 MTPA (47 percent of 22.5 MTPA total capacity). SPAs totaling 8.4 MTPA have been signed to date. The remaining 53 percent (12 MTPA) of capacity will target shorter-term and spot market deals.

Interestingly, of the seven entities that have entered 20-year SPAs for capacity at Corpus Christi at fixed liquefaction fees of $3.50 an MMBtu (LNG costs indexed at 115 percent of Henry Hub), five are European-based utilities/traders (Endesa, Iberdrola, Gas Natural Fenosa, Électricité de France, and EDP/Energia de Portugal). The others are Australia’s Woodside Energy Trading and Indonesia’s PT Pertamina. This illustrates that U.S. LNG exports can and will be sold into the worldwide market, and not just into Asia, which at one point was viewed as the primary destination for U.S.-sourced LNG shipments.

E. Russell “Rusty” Braziel is president and chief executive officer of RBN Energy LLC in Houston, an energy consultancy providing analysis and advisory services. He spent 20 years with Texaco (now Chevron), serving as vice president of natural gas marketing and trading, and manager of natural gas liquids supply. Subsequently, Braziel was vice president of business development for The Williams Companies, President of Altra Energy Technologies, and co-owner of Bentek Energy. He holds a B.B.A. and an M.B.A. in business and finance from Stephen F. Austin University.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.