Oil and Gas Hedging

LINN Energy LLC Hedging Strategies Maximize Cash Flow, Fuel Organic Growth

By Colter Cookson

HOUSTON–When Mike Linn formed LINN Energy in 2003, it had a small staff, one office, and a handful of operated natural gas wells in the Appalachian Basin. Today, LINN Energy LLC is worth approximately $9.5 billion. With 2.7 trillion cubic feet equivalent in proven reserves, 700 employees located at more than two dozen offices, and 11,000 producing wells in multiple core operating areas, the Houston-headquartered company is among the top 20 domestic independent exploration, drilling and production companies.

LINN Energy has a simple strategy: Acquire and optimize producing assets with predictable returns and long reserve lives. This strategy is nothing new. According to President and Chief Executive Officer Mark Ellis, the company owes its success to a combination of hard work, luck and determination. “We try to be creative in the way we grow,” he adds.

To illustrate, Ellis points to the company’s $2.05 billion acquisition of Dominion’s Mid-Continent oil and natural gas properties in 2007. “We bought an asset that was larger than us,” he says. “We were like a dog chasing a car, but unlike the dog, we caught the car and knew what to do with it.”

Chief Financial Officer Kolja Rockov says that year was pivotal for the company. “We started the year with an acquisition that doubled the company’s size, waited a few months, and made a larger acquisition that doubled the size again,” he recalls. “Then we did the Dominion transaction and more than doubled the company’s size again.”

Before it acquired Dominion’s Mid-Continent assets, LINN Energy made another gutsy move: In 2006, it became the first publicly traded limited liability company to focus on oil and natural gas development. Ellis says the new corporate structure makes it easier for the company to raise capital.

“We use a limited liability structure, which utilizes elements of a master limited partnership, and a C-corp,” Ellis notes. “Like a master limited partnership, we pay a significant portion of the cash we generate to our unit holders in the form of a quarterly distribution. Our quarterly distribution is a healthy 66 cents per unit. or $2.64 on an annualized basis, which represents a yield of about 6.6 percent.

“Unit holders receive benefits for investing in oil and natural gas, including tax-advantaged distributions,” Ellis continues. “Coupled with our low-risk growth strategy, our structure’s tax benefits make us an appealing buy for investors seeking a steady income.”

The low-risk strategy and tax benefits have a profound effect on investors’ expectations, Ellis says. “Our investors are looking for current income, which they find in our distribution. Our overall strategy gives us a lower cost of capital, which provides us with a competitive advantage relative to the publicly traded C-corps.”

Ellis offers another way to explain the MLP/LLC capital cost advantage: trade multiples. “Our shares trade at more than seven times our earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization when C-corps trade at five to six times EBITDA,” he reports. “We can buy assets at six to seven times EBITDA, and they will be accretive to us when they would not be for a C-corp.”

Rockov says he sees the MLP/LLC structure as a great fit for LINN’s acquire-and-optimize strategy. “Our cost of capital typically is significantly lower than a C-corp, which allows us to be more competitive in buying assets,” he explains. “That is really what makes our model go.”

Acquisition Strategy

Ellis says LINN Energy’s acquisition strategy has one goal: providing low-risk, long-term cash flow increases. “At its root, our strategy is about acquiring a cash flow stream, then hedging to eliminate the financial risk associated with generating that stream,” he elaborates. “That cash flow can come in the form of a natural gas asset, an oil asset, or a liquids-rich natural gas asset. All of those work for us, as long as the property has a high margin.”

In addition to a long life and high margins, Ellis says potential acquisitions must meet several other criteria. “The assets need to have investment opportunities that will generate returns high enough to compete for capital within our portfolio. They also need to be located in areas where we feel comfortable operating and can hedge the production,” he details.

If an acquisition passes those hurdles, the company will conduct a cash flow analysis. “When we look at an asset, we are interested in how much extra cash flow we get by buying the asset,” Rockov says. “We consider upside potential, but given our low-risk strategy, every deal we do has to be immediately accretive to our unit holders.”

The emphasis on immediate, low-risk and long-term gains pleases LINN’s unit holders, Rockov says. “With each acquisition boosting our long-term cash flow, we expect to not only maintain our distribution, but have the potential to increase it,” he explains. “That is what gets our investors excited.”

Since it went public in 2006, LINN has completed 45 acquisitions worth a total of $6 billion. “Coupled with organic growth, these acquisitions have enabled us to increase our quarterly distributions from $0.40 to $0.66 a share, or 60 percent,” Rockov reports.

Recent Acquisitions

LINN Energy has continued to snap up properties, Ellis says, noting that it already has signed agreements for $637 million in acquisitions in 2011. “So far, we have acquired reserves at an average cost of $19.15 for each barrel in the ground,” he reports. “That cost is almost twice what we achieved in 2009, but since we are selling the oil at close to $100 a barrel, we still get a great profit.”

The 2011 transactions include a $196 million entry into the Bakken Shale area of the Williston Basin, which the company closely followed with agreements for two bolt-on acquisitions for a combined contract price of $163 million. “The Bakken Shale is one of the premier oil plays in the United States,” Ellis notes. “Oil there has a lifting cost around $5 a barrel and a finding cost around $10 a barrel. Since we will be selling the production at $90-$100 a barrel, the area gives us a significant margin.”

By utilizing the low cost of capital that comes from its corporate structure, which combines aspects of a master limited partnership and a C-corp, LINN Energy has acquired low-risk, long-lived assets with attractive margins. Coupled with strong hedge positions and low-risk development drilling, these acquisitions have enabled LINN Energy to provide stability and growth.

The company also has expanded its stake in the Permian Basin. “We entered the Permian Basin through an acquisition in the summer of 2009,” Ellis relates. “We knew we wanted to grow the Permian into a core area for the company and establish a presence in the Wolfberry oil trend, so we started pursuing companies that were active there, expressing our interest in acquiring some of their assets. Today, after 10 additional completed transactions, the Permian Basin accounts for 20 percent of our corporate production.”

Ellis says he is pleased with this year’s closed and pending acquisitions in the Bakken Shale and Permian Basin. Together, they should provide 4,000 barrels of oil equivalent a day, with approximately 90 percent being oil or natural gas liquids, Ellis indicates. He adds that they offer great opportunities for development drilling, which the company plans to pursue.

“Aggressive development drilling is unusual for MLPs, which typically prefer to focus on acquisitions over organic growth,” Ellis observes. “A few years ago, we fit the typical MLP model, allocating less than 5 percent of our capital to organic growth. But over the years, because of the major transactions we have done and the size our company has reached, we have acquired a large inventory of high-return development drilling opportunities.”

These include 1,000 oil and NGL-rich locations in the Granite Wash, the Wolfberry and the Bakken Shale, Ellis reports. “To take advantage of those opportunities, we plan to increase our spending on drilling significantly,” he says. “We expect to drill 35 horizontal Granite Wash wells and more than 130 Wolfberry wells this year, and we anticipate an aggressive drilling program in the Bakken Shale as we expand our footprint there.”

These low-risk, high-return opportunities fit the LLC/MLP model, Ellis says. “When we drill them, we get our investment back quickly and gain an asset that will generate a cash flow stream for many years to come,” he states. “They offer an efficient way to grow cash flow.”

Although LINN is spending more on organic growth than it has in the past, Ellis says the company plans to continue focusing on acquisitions as well. “The acquisition market is full of opportunity right now,” he says. “And we have the dry powder to continue to be a very active acquirer. We have accessed the capital markets through a $649 million public equity offering that provided net proceeds of approximately $623 million. We also retired 81 percent of our highest-cost debt, which will reduce interest expense significantly.”

Most of the company’s acquisitions will expand its footprint in its existing operating areas, Ellis predicts. “We are involved in most of the basins we want to be in, especially now that we have established a position in the Williston,” he says.

Hedging

Whether LINN is increasing cash flow through acquisitions or organic growth, hedging will remain a key part of its strategy. “Hedging protects our profit margins, which allows us to have the predictable cash stream that drives our quarterly distribution,” Rockov remarks.

According to Ellis, the company hedges soon after it acquires a property. “We could try to wait until prices peak, but after 30 years in the oil and gas business, I still do not know anyone who can predict prices,” he says. “Instead of betting on our crystal ball, we hedge when we make a major acquisition. That locks in the economic bargain we negotiated.”

Rockov says hedging has been more beneficial during downturns than the company initially expected. “When prices go down, our production taxes and other expenses fall, but our revenue stays the same,” he explains. “The hedge not only protects our margin, but also allows us to have a higher cash-flow margin during periods of depressed commodity prices.”

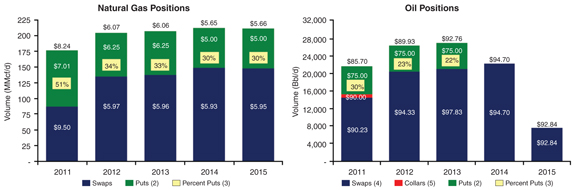

Although it hedges most of its production, the company also benefits when prices go up, Rockov continues. “On average, 20-30 percent of our hedge positions are puts, which establish a floor but have unlimited upside. There is not a good way to hedge NGL production as far as we would like, so our NGL production remains unhedged,” Rockov says. “That means when prices go up, we effectively get one-third of the benefit on oil and all of the benefit on NGLs.”

In addition to allowing upside, the puts mitigate the risk that swaps would pose during extreme price upswings. “In exchange for a payment equal to the price we want to lock in, swaps require us to pay the financial institution based on an indexed oil price,” Rockov notes. “Risks include the price of oil skyrocketing, or the company producing less volume than expected. Puts alleviate both risks because they allow us to benefit from high prices and are only options, not obligations.

“If puts were free, we would hedge all of our production using them and have all the upside,” Rockov muses. “They are not, so we need to balance their potential for upside with their cost and the risks associated with swaps. After 45 acquisitions and many cost/benefit analyses, we think we have perfected the art of buying and hedging. A ratio of 20-30 percent puts and 70-80 percent swaps almost always seems to emerge as the right choice.”

That ratio emerges partly because LINN prefers to limit its spending on hedging to 10 percent of an asset’s acquisition price. “If we buy an asset for $100 million, we are fine spending between $5 million and $10 million on hedging, which is essentially an insurance policy,” Rockov says. “That extra cost lets us buy puts covering 20-40 percent of the asset’s production, but it is not enough to affect our margin. If we go too far over 10 percent, the hedges start to get too expensive relative to our spending on real assets and the margin starts to decline.”

As the company’s initial hedges mature, it needs to add additional layers, Ellis notes. “Our goal is to have positions at least as far out as five years, with a strong position over the next three to four years,” he says.

Rockov says the company arrived at the five-year goal from experience. “Five years is long enough that the hedge will last at least one, and maybe two, cycles,” he says. “If we only hedged two or three years out and prices went down, we would not be able to renew the hedges at the same price, which would expose us to risk that we do not want to take.”

The five-year goal has a more interesting benefit: It leads to higher prices. “In almost any time period, the price curves for oil and gas are in contango, which means they slope upward,” Rockov says. “For example, the natural gas price is in the $4.50 range now, but the five-year average price is at $5.50. If we hedge over that period, we can get $5.50 now. So reaching out farther allows us to benefit from upward price predictions.”

According to Rockov, that can lead to higher returns than participating in actual upswings. “As a general rule, this business has a lot of optimism,” he says. “The market usually underperforms the forward price curve.”

When the price plummets, hedges enable the company to stay strong. As proof, Ellis points to LINN’s distributions during 2008 and 2009. “Despite the volatility in the credit and commodity-price markets, we were able to generate enough cash flow to keep our distribution at its 2007 level,” he says. “That was largely because of the strength of our long-term hedge positions.”

With the economy recovering, LINN managed to raise its distribution in 2010. “Our organic growth and acquisition activity is going well, so we anticipate we will be able to raise the distribution again this year,” Ellis adds.

Funding Acquisitions

LINN’s appeal to investors has enabled it to raise more than $7 billion in funds through the capital market, Rockov says. “I am proud to say that from the time we went public in 2006 to today, only one oil and gas independent and none of the other master limited partnerships have raised as much capital as we have,” he reports. “Given our size early on, that is quite a feat.”

Rockov says LINN has been so successful partly because its business model fits with the goals of most MLP investors. “Our unit holders appreciate that we buy low-risk assets, remove the commodity price risk, capture the margin between oil prices and acquisition costs, and send our excess cash flow back to unit holders through a quarterly distribution,” he says. “We have stability, so we trade at a significant cost-of-capital advantage.”

But when the company first went public, it faced an uphill battle convincing investors that an upstream MLP could work, according to Rockov. “Anyone who tries to pioneer a new concept as a small, unknown entity is going to face a tough sale,” he says. “We embraced that challenge. I think we were successful largely because our enthusiasm for the model came through. In the end, that enthusiasm and the logic behind the model overcame the skepticism.”

The skeptics generally pointed out that upstream MLPs failed in the 1980s, Rockov recalls. “There are a whole bunch of reasons for that. They were not run the same; the modern MLP, like the ones pioneered in the 1990s, did not exist. Also, oil prices were $10 a barrel and interest rates were at 20 percent. No income-based security works under that kind of market,” he responds. “Midstream MLPs work because they do not have commodity price risk. We work because we hedge commodity prices to get around the risk.”

The other common objection held that an upstream MLP would fail because it would need to spend too much money compensating for its acquisitions’ production decline curves. “It is true that we have to spend more maintenance capital than a midstream MLP to keep our production flat,” Rockov acknowledges. “But most of the properties we buy have infill, low-risk development locations. We have to reserve more cash flow, but the margins between what we buy and what we trade allow for that.”

Ellis points out that in 2010, LINN replaced 321 percent of its reserves through drilling at an average finding cost of $0.79 an Mcfe. Including acquisitions, the company replaced more than 1,000 percent of its reserves at $1.69/Mcfe.

Today, Rockov says LINN has a much easier time raising capital. “We used to face a head wind,” he recalls. “With the success we have enjoyed, we now have a significant tail wind. There are still pockets of capital that have never heard of us, but there are also many people who are fans of LINN and have been for a long time.”

When the company needs to raise capital, Rockov says it tries to do so through 60 percent equity and 40 percent bonds. “Our bond investors are just as important to us as our equity investors, and they look at several metrics that the 60/40 ratio helps us maintain,” he explains. “The most important one is debt to EBITDA, or debt to operating cash flow, which we want to be three times or less. The ratio allows us to be right at that number, and as we acquire more assets, we can bring that number down. In other words, we are deleveraging the company as we grow.”

As the company has expanded and established its track record, it has been able to issue bonds at lower interest rates, Rockov reports. “Our credit rating used to be lower, so we issued bonds with interest rates from 9.875 to 11.75 percent,” he says. “Today, we can issue bonds at interest rates below 7.0 percent. To benefit from that rate, we have used proceeds from equity offerings to retire the high-cost bonds at par plus coupon. We also put a tender for our bonds at a price 3-4 percent higher than their trading price and got most bondholders to agree. We paid above the bonds’ value in both cases, but we expect that will let us reissue the bonds at lower interest rates. This will save us more than $40 million a year in interest expense.”

The Future

Ellis and Rockov express confidence in LINN’s future. “As the first upstream with an MLP-type structure, we have a front-runner advantage,” Ellis says. “Our enterprise value is about $9.5 billion, almost the size of all our competitors together. That size gives us the ability to access capital at lower costs. It also lets us raise the amounts needed for larger transactions, so we can grow in larger chunks.”

Ellis says the company has considerable room to grow. “The entire MLP space, including the midstream and upstream MLPs, has $340 billion in enterprise value,” he observes. “The upstream sector only accounts for $20 billion of that total. It is in the very early stages of growth, so the question becomes how much it can grow. I do not have the exact answer to that, but because the United States has a vast pool of long-life reserves we could potentially acquire, we have great potential to grow.”

Rockov concurs. “Our asset class is very, very large,” he says. “Our enterprise value is close to $10 billion, and we plan to grow. Large midstream MLPs are worth $40 billion-$50 billion.”

The challenge will be keeping ahead of the other companies that want a piece of the market, Rockov muses. “We think we will do well,” he says. “We are getting larger and more stable every day, so our cost of capital continues to go down. That allows us to pay more for the assets than our competitors, but get the same financial result.”

Another challenge is keeping the fast pace, Rockov says. “It takes effort to buy and assimilate assets at the pace we are going now,” he relates. “For example, last year, we screened 189 acquisitions, bid on 41 transactions for a total of $10.1 billion, and won 14 bids. That takes a lot of work.”

However, that work is easier now than it used to be, Rockov says. “When you are a small company, you have to do extraordinary things to buy assets and assimilate them while continuing to run your business,” he recalls. “What we tried to do, particularly in 2008 and 2009 when the market slowed, is build our acquisition teams. Today, we have teams that evaluate transactions efficiently and appropriately, as well as human resource, information technology, accounting, HSE, and engineering departments that can integrate acquisitions quickly. That makes the process much easier.”

Ellis says he is sure the company’s size and value will continue to grow. “We want to keep our front-runner’s advantage,” he stresses. “We will make sure that no matter how large we get, we continue to strive for growth and continue to be creative in the way we achieve it.”

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.