Rejuvenated Appalachian Basin Provides Economic Boost To Northeastern United States

By Al Pickett, Special Correspondent

Sometimes it is nice to stop and smell the roses.

Within the span of a dozen years from the 2004 drilling of the Marcellus discovery well in Washington County, Pa., oil and gas operators ramped up natural gas production in the Keystone State to 5.1 trillion cubic feet. That record-high annual production total in 2016 represented a 65-fold increase over 2009, when Pennsylvania’s Marcellus output was 78.4 billion cubic feet, and placed it behind only Texas as the largest gas-producing state in the union.

George Stark, director of external affairs for Houston-based Cabot Oil & Gas Corporation, says it is important to pause occasionally and reflect on what the industry has accomplished in its remarkable development of the Marcellus and Utica shale plays that have rejuvenated the historical Appalachian Basin.

In an early summer update to community and elected officials in Montrose, Pa., Cabot announced several milestones from its previous decade of operations in northeastern Pennsylvania. The 10-year look-back included the announcement that Cabot had paid more than $1.0 billion in royalties to landowners in Susquehanna and Wyoming counties, and nearly $500,000 in signing bonuses since it commenced operations in 2006.

“We are living through history,” Stark attests. “The amount of gas there is mindboggling. We can see the economic development from the taxes paid to county governments and school districts, as well as to farmers who now have new equipment and can afford to send their kids to college. It is huge for Susquehanna County, which is where most of our operation has been. We lose sight of this sometimes when we get so busy working.”

Stark points out that Cabot has 200,000 mostly contiguous acres in the region and has drilled 525 wells, completed more than 10,000 fracture stages, and produced 3 trillion cubic feet of pipeline-quality dry natural gas from the Marcellus Shale during the last 10 years.

With daily production of nearly 2 billion cubic feet, he claims Cabot is producing 3 percent of the nation’s natural gas from Susquehanna County alone. He adds that although Susquehanna County is one of Pennsylvania’s largest geographically, its status as one of the state’s more rural counties–with a population of only 47,000–makes the $1 billion in royalty payments that much more impactful.

When Cabot drilled its first Marcellus well a decade ago, the company listed its estimated ultimate recovery at 8 billion cubic feet. Ten years later, Stark says Cabot’s Marcellus EURs average 28 Bcf, an increase he attributes to longer laterals, more frac stages spaced more closely, the ability to drill faster, a better understanding of the rock and the professionalism of Cabot’s employees.

He says Cabot plans to drill 60 wells this year with average lateral lengths of 8,000 feet and more than 50 frac stages.

Most of Cabot’s gas heads northeast to New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts and Connecticut. As new pipelines are built and others are reversed and retrofitted, Stark says he anticipates future production will be sent down the East Coast and ultimately to the Midwest.

He admits the industry often is a victim of its own success, noting that 2016 was Cabot’s worst year for realized natural gas prices. “But this rock is so predictable, it almost is like having gas storage in place,” Stark relates.

Diversified Portfolio

Like Cabot Oil & Gas, Southwestern Energy is active in northeastern Pennsylvania, but thanks to an acquisition, Southwestern has exploration, drilling and production operations in southwestern Pennsylvania and West Virginia as well.

Northeast Appalachian Division Leader David Dell’Osso says Southwestern holds roughly 250,000 net acres with historical concentration in Bradford and Susquehanna counties, Pa., although it has expanded into Pennsylvania’s Tioga and Wyoming counties as well.

“We have drilled more than 400 operated wells in northeastern Pennsylvania and have gross operated production of around 1.3 Bcf/d,” he reports. “Our first well went to production in July 2010.”

Cabot Oil & Gas Corporation has produced 3 trillion cubic feet of pipeline-quality dry natural gas from the Marcellus Shale over the last 10 years, and has paid more than $1.0 billion in royalties to landowners in Susquehanna and Wyoming counties, Pa., along with nearly $500,000 in signing bonuses since it commenced operations in 2006. With daily production of nearly 2 billion cubic feet a day, Cabot says it is producing 3 percent of the nation’s natural gas from Susquehanna County alone.

Dell’Osso says Southwestern tries to “get out of the way of the reservoir as much as possible” by utilizing bigger flowlines and larger separation vessels to enable higher gas production rates. He adds that its northeastern Pennsylvania gas is near pipeline quality when it comes out of the reservoir. “We dehydrate it and do little else to achieve pipeline specification, which is an advantage from a cost standpoint,” he reflects.

Historically, Dell’Osso says, Southwestern has drilled 5,000- to 5,500-foot laterals on average, but has expanded that over time and recently drilled some laterals beyond 10,000 feet. In the northeastern part of the state, he says, laterals tend to be limited less by equipment and surface leases than by subsurface faulting.

Dell’Osso says Southwestern is testing a variety of sand loadings in an effort to establish the point of diminishing economic returns, which will enable the company to optimize economics in a variety of commodity price and service cost combinations. It has shifted to a tighter stimulation design with around 2,000 pounds of sand per foot of completed lateral in a more intensive completion strategy, and he says the company expects to bring 67-75 wells to sale this year.

Jack Bergeron, Southwestern’s senior vice president of operations, revealed in the company’s first-quarter earnings report that the first 39 wells it placed to sales this year had cumulative production that outperformed offsets by approximately 130 percent in their first 150 days. As a result of completion and optimized flowback changes being implemented, he says the average EUR improved by more than 25 percent compared with historical well results in Susquehanna County.

Southwestern also placed seven delineation wells to sales in Tioga, Wyoming and Susquehanna counties in the first quarter. The two wells in Tioga County each had an average lateral length of 6,700 feet and an average 30-day rate of 13 MMcf/d. Bergeron says these wells are expected to improve as compression is added.

He says the two wells in the western part of Susquehanna County–on acreage acquired in 2015–are outperforming offsets by more than 100 percent and each had an average 30-day rate of 15 MMcf/d.

Thanks to the successful results in these areas, Bergeron says Southwestern has derisked approximately 40,000 net acres and plans to continue delineation efforts throughout this year.

Dell’Osso says Southwestern has access to multiple high-quality pricing locations through its low-cost, integrated firm transportation portfolio.

He acknowledges that Southwestern previously built its northeastern Pennsylvania operations to win in a $4 gas price environment, but says it has chased improvements to make its operations profitable at lower commodity prices. Dell’Osso says the company has restructured many of its gathering agreements, which in turn has lowered its cost structure.

He indicates Southwestern also has used a hedging program to manage and mitigate risk, and to buffer the company against price volatility.

Stacked Pays

Meanwhile, Southwestern’s operations in West Virginia and southwestern Pennsylvania target stacked pays that include the Marcellus, Utica and Upper Devonian formations.

“We have nothing west of the Ohio River,” remarked Derek Cutright, Southwest Appalachia division leader, in June. “The majority of our wells are in the Marcellus. We have more than 300 producing Marcellus wells and three Utica/Upper Point Pleasant wells.”

Southwestern acquired the assets in late 2014 and early 2015, and has approximately 321,000 net acres and plans to turn 52-60 wells to sales in 2017.

A Southwestern Energy rig is shown here drilling in the northern West Virginia Panhandle, where the company has Marcellus, Utica and Upper Devonian targets, thanks to a 2015 acquisition. Southwestern says its first Utica well was flowing at 17 million cubic feet a day in April, and has an estimated ultimate recovery of 2.5 billion-3.0 billion cubic feet per 1,000 feet of lateral.

“The majority of activity is in West Virginia’s northern panhandle, which is liquids rich,” Cutright continues. “The Marcellus has about 40 percent gas and 60 percent liquids. As you go south into Wetzel County, it is the reverse: about 60 percent gas and 40 percent liquids. Most of West Virginia is liquids rich. As you move east into Greene County, Pa., you are back into dry gas.”

The Utica formation, which lies below the Marcellus Shale, is dry gas, according to Cutright. He says Southwestern is in the delineation phase of its Utica exploration to determine what the Utica offers to compete with its Marcellus operations.

The company’s first Utica well, the OE Burge, was flowing at a flat rate of 17 MMcf/d in April with more than 8,500 psi of pressure. Early results indicate this well is top quartile for the region, with an EUR of 2.5 Bcf-3.0 Bcf per 1,000 feet of lateral. Bergeron claims this type of productivity shows the Utica’s potential in the company’s estimated 1,400 locations.

Cutright explains that Southwestern continues to look for ways to make improvements within its performance strategy of completion optimization, lateral placement and flowback techniques to maximize hydrocarbon recoveries.

“We have moved our completion strategy from 1,700 pounds of sand per foot to 2,500 pounds per foot with positive results (about a 20 percent improvement in EUR),” he offers. “We are testing 2,500-3,500 pounds per foot in the liquids-rich wells. In fact, we have tested as high as 5,000 pounds per foot, although we have pulled back from that. We are in phase two of testing with a more intensive completion strategy, and we are seeing a 40 percent uplift.”

Southwestern placed five wells on line that tested tighter stage spacing and increased proppant loads. Four of them were completed utilizing 140-foot stage spacing and 3,500 pounds of proppant per foot, while the fifth well utilized as much as 5,000 pounds of proppant per foot. The company is continuing to monitor these five test wells to determine long-term performance enhancements, according to Cutright, but early indications are that all five will perform better than their closest offsets.

He says Southwestern continues to challenge its completions-optimization team to accomplish more with less cost.

A Shift To E&P

Much of CONSOL Energy’s 153-year history in the Appalachian Basin involved coal mining. But Brian Aiello, director of communications for CONSOL, says the company expects to complete splitting its coal mining and natural gas divisions by the end of the year. “That will free both entities,” he remarks. “They won’t be competing for capital.”

CONSOL has become a giant natural gas producer with 6.3 Tcf equivalent of proved reserves. Craig Neal, vice president of operations for the E&P Division, says CONSOL has reduced its leased acreage slightly from a peak of 1.4 million acres after a swap with Noble Energy. “But we picked up core acreage in West Virginia,” he says.

CONSOL is targeting both the Utica and Marcellus shale in southeastern Ohio, southwestern Pennsylvania and West Virginia.

“Through May, we had drilled 15 wells with two horizontal rigs,” he reports. “I am proud that we have been able to take a well to total depth about every 10 days.”

CONSOL Energy’s primary focus this year has been in Monroe County, Oh., drilling dry gas Utica wells. Neal says the company also has drilled two dry-gas Utica wells in Westmoreland County, Pa., which are offset from its successful Gaut pad.

“These are deeper wells,” Neal states. “The first well took 43 days to drill. We drilled the second well in 34 days. We expect to get that down to 25 days or fewer. We also have drilled a couple of Marcellus wells in Washington County, Pa.”

He says CONSOL Energy has a mix of Utica dry gas in southwestern Pennsylvania and Monroe County, Oh., and the more liquids-rich Marcellus in southwestern Pennsylvania and West Virginia. It also has some wet gas drilled-but-uncompleted wells in West Virginia that it acquired in the Noble transaction.

Improved Efficiency

CONSOL Energy increased its production guidance for 2017, according to Neal. In fact, it has doubled its Marcellus well EURs. He says it has been able to do that through a number of factors that improve efficiency. For example, by reducing drilling and completion cycle times, Neal says CONSOL has been able to bring the average pad on line 30 days sooner.

“That reduces the time from when we spend the first dollar to when the first dollars come in,” he imparts. “Another contributing factor is reducing our production downtime by 72 percent. We have been able to improve efficiency without sacrificing our core value of safety and compliance. We have kept our safety record intact.”

Neal says CONSOL Energy has increased it proppant loads to as much as 4,000 pounds per lateral foot. It has increased lateral stage spacing from 1,100 feet to 1,500 feet. He says the company also is targeting 11,000-foot-plus lateral lengths, when possible.

By switching from 5-inch to 5½-inch OD tubulars, Neal says CONSOL Energy has reduced friction pressure, allowing it to speed its drilling mud and clean the holes quicker, which enables it to employ larger cylinders in its pumps, which he notes is one more way CONSOL has improved efficiency and EURs.

CONSOL Energy’s average EUR is 2.8 Bcf per 1,000 feet of lateral in its Monroe County wells, according to Neal.

He adds that CONSOL also has been able to sign new contracts with pipeline carriers taking gas out of the Appalachian Basin, which resulted in better pricing from fourth quarter 2016 to the first quarter of this year.

“I recently passed four pipeline projects on my way to a rig site on Highway 558,” Neal comments, noting the continuous efforts to get the region’s abundant gas to multiple markets.

“Even at $2.50 before taxes, these wells have a 90 percent rate of return,” he enthuses. “We are extremely happy with them. We have reduced our costs to $9 million a well.”

Pad Drilling

By June, CONSOL Energy had drilled its SWITZ 16 and SWITZ 5 Utica pads in Monroe County, Oh., and the PENS 2 Marcellus Shale pad in Ritchie County, W.V., according to Neal. The company also has drilled the SWITZ 28 and SWITZ 26 pads, and moved to the SWITZ 7 pad. Neal says he expects production from the SWITZ 28 in the third quarter and production from SWITZ 26 by early in the fourth quarter.

Neal says the company is drilling four wells a pad in Monroe County, and usually six-eight wells a pad in the Marcellus. “That seems to be the right mix for us,” he reflects. “If you drill too many wells on a pad, it delays the time to begin receiving income from those wells.”

CONSOL Energy is targeting both the Utica and Marcellus shales in southeastern Ohio, southwestern Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. Through May, the company had drilled 15 wells with two horizontal rigs. CONSOL says it is using as much as 4,000 pounds of proppant per lateral foot, and has increased lateral stage spacing from 1,100 to 1,500 feet.

He adds that CONSOL’s frac crew working on the SWITZ 28 pad was able to move to an adjacent pad 800 feet away and fracture eight wells without rigging down.

Frac design optimization and improved logistics resulted in CONSOL Energy fracturing an average of 1,245 feet a day, compared with 800 feet a day in 2016. At that pace, with pads drilled and ready to fracture, a crew can complete 46 Marcellus wells a year with an average lateral length of 8,000 feet, he says.

CONSOL Energy also set a record by drilling a 7,380-foot Marcellus lateral in Washington County, Pa., in only 23 hours.

“Our team is laser-focused,” Neal lauds, noting the company has employees with 20-30 years of experience. “I expect we will break that record this year.”

Neal points out that CONSOL’s guidance says it will drill 25 wells total in 2017 in the Pennsylvania dry gas window. “We are capable of doing more, but that may depend on the price,” he adds.

In January, CONSOL Energy finished completion activity on its ACAA 1 pad at the Pittsburgh International Airport in Allegheny County, Neal mentions. The ACAA 1 pad contains six Marcellus wells as well as one Burkett and one Rhinestreet well.

“We are testing the Burkett and Rhinestreet,” Neal explains. “Our results are very preliminary; we will have more to report later.”

Three of the Marcellus Shale wells were turned to sales in the first quarter with the remaining five carrying into the second quarter. Neal says all the wells on the airport lease are wet gas.

Longer Laterals

Dennis Degner, vice president for the Appalachia division of Range Resources, contends the future emphasis in the Marcellus and Utica plays will be on longer lateral completions. “I think the continual process to make longer laterals successful and repeatable for the strongest returns will be the strategy for the next couple years,” he predicts.

Range drilled three laterals in excess of 15,000 feet in the first five months of 2017, according to Degner, including the longest Marcellus lateral drilled to date. That well was in Washington County, Pa.

“Those three wells started producing in June,” he states, “so it is a little early, but we are encouraged by the results.”

Drilling longer laterals faster is the end result of a number of factors. Degner lists bit selection, improved rotary steerable tools and an improved mud program among the elements that have helped Range drill faster.

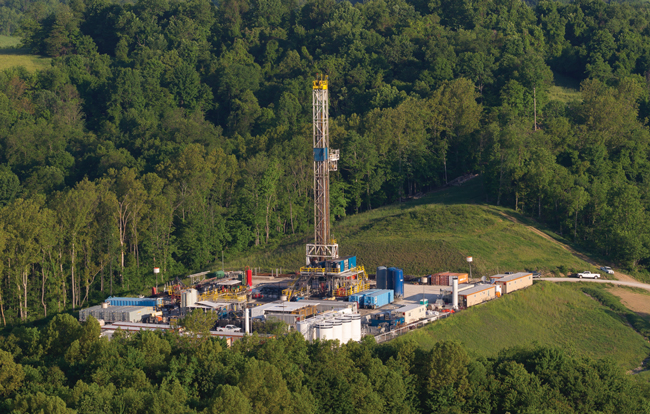

Range Resources, shown here at a location in southwestern Pennsylvania, drilled three laterals in excess of 15,000 feet during the first five months of 2017, including its longest Marcellus lateral to date in Washington County, Pa. According to Dennis Degner, vice president for Range’s Appalachia Division, bit selection, improved rotary steerable tools and an improved mud program have helped the company increase drilling rates.

“On the completion side, the big leaps came between 2011 and 2015,” he relates. “The increases in efficiency may come now from higher sand concentrations.”

Focus On Marcellus

Range has 1.5 million net acres of stacked pay potential across Pennsylvania. Although it has completed a couple dry gas wells in the northeastern region of the Keystone State, the company isn’t drilling in that area at present. Instead, it has seven rigs operating in southwestern Pennsylvania, which offers multiple horizons, including the Marcellus, Utica and Upper Devonian. The company refers to that area as “super-rich,” with at least 1,200-1,250 Btu gas. It also has as a wet gas area (1,050-1,200 Btu) and a dry gas area with pipeline-ready gas.

Degner says Range “remains focused on our Marcellus assets for production growth. Our consistent improvement in capital efficiency and well performance over the last decade has made the Marcellus well activity difficult to beat.”

Degner, who oversees Range’s entire Appalachia Division since the company combined its southern and northern Marcellus divisions earlier this year in an effort to streamline operations and reduce costs, says, “Since there is no NGL component in dry gas, it is not burdened with the cost of processing. The super-rich and wet gas offer additional revenue streams, but you have to pay for processing.”

During the past 12 months, Range has moved to what Degner calls “a place of big data,” which he says “allows us to look at the economics and move from one project to another (depending on commodity prices).”

The Btu diversity of Range’s assets requires the company to take different approaches to proppant loading, depending on whether the gas is dry or wet, Degner offers.

“We tend to use smaller amounts of proppant in dry gas wells, but we have tested larger jobs with encouraging results,” he adds. “It just depends on what delivers the most.”

He says Range is using two-and-a-half times more frac stages than it did in 2010, noting its average Marcellus lateral is approaching 9,000 feet and 45 frac stages.

During the first quarter, Range drilled and completed four super-rich wells from a pad located in a lightly drilled area near the planned Harmon Creek processing plant in northwestern Washington County, Pa. Because of their high initial production rates, only two of the wells were brought on line. Degner says those two wells produced a combined 62.8 MMcfe/d from an average lateral length of 10,772 feet with 54 frac stages. The remaining two wells on the pad will be brought on line when gathering capacity is available.

“MarkWest has a looped gathering system, so we can take our gas to two processing plants–the Houston plant near Canonsburg, Pa., and another at Majorsville near the Pennsylvania-West Virginia border,” he comments. “When the Harmon Creek plant comes on line sometime in 2018, it will allow us to expand our operations farther north.”

He notes that MarkWest has removed the original Houston plant to upgrade to a 200 MMcf/d cryogenic plant, increasing processing capacity by 170 MMcf/d.

Existing Pads

Degner says Range Resources plans to turn a total of 116 Marcellus wells to sales this year, consisting of 39 in its super-rich area, 45 in the wet gas area and 30 dry gas wells in southwestern Pennsylvania, in addition to the two dry gas wells recently completed in northeastern Pennsylvania.

In addition to drilling longer laterals, lowering costs and increasing recoveries in an effort to improve capital efficiency, he says Range also will drill approximately one-third of its 2017 wells from existing pads. “As the play unfolded, we started to think long-term,” Degner relates. “Initially, most of our pads had four-six wells, but we plan for the ability to put up to 20 wells on each pad.”

By being able to go back to a pad site, he says the company believes it will save $200,000-$500,000 a well.

The average EUR for Range’s wet gas wells is 2.5 Bcfe-3.0 Bcfe per 1,000 feet, according to Degner. “Some areas are stronger,” he adds. “Because Range was an early mover in the play, we have been ahead of some of the constraints. We have enough take-away, and we feel good about our projects.”

Range focused on infrastructure early on, he notes, trying to think creatively to get its natural gas liquids to premium markets. “We were the first to take our methane and ethane out of the basin,” he elaborates.

Degner says Range will remain dedicated to its recycling program, as well. He says the company is recycling 100 percent of its flowback water and has facilitated water agreements with other operators to take their produced water too. By doing that, he reports, Range has to use freshwater for less than 50 percent of its hydraulic fracturing operations.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.