Production Automation

Strategic Approach Key To Implementing Effective Automation Solutions

By David Wray

THE WOODLANDS–The growth of unconventional resource plays is driving renewed demand for automation and monitoring technology in U.S. oil and gas production operations. Characteristics such as high initial productivities and rapid declines in individual well production curves, as well as operational drivers such as the number of wells and amount of equipment required to produce these assets, give oil and gas resource plays unique challenges that can be addressed through automation. When implemented properly, an effective field automation strategy optimizes production and minimizes downtime–whether an individual wellhead or multiwell pad, to a single tank battery or centralized facility.

However, while automation equipment can offer tremendous labor savings and additional revenue, many companies gain only a fraction of its benefits. Unlocking automation’s full potential requires planning and a framework that few companies realize are necessary when they make the transition from manual processes to automated ones. Fortunately, an efficient approach can result in significant monetary and manpower savings.

Consider a company that had spent $34 million on supervisory control and data acquisition equipment and software. The company had all the hardware it needed for automation, but because the hardware sent data to eight disparate systems, using that data to make better decisions required a monumental effort. As a result, the company only saw 15 percent of the return its equipment should have provided and would need decades to recoup its costs.

Fortunately, the company had an option. By standardizing and aggregating its data so employees only had to work with one or two systems (a process that would cost only $500,000-$600,000), the company recovered the cost of the equipment in only nine months.

It is not alone. For many companies, adopting an enterprisewide automation strategy can increase revenues significantly by reducing the amount of time employees spend on clerical work, such as inputting data or transferring them from one system to another. While the automation have-nots spend 35-50 percent of their time engaged in clerical work, those with an effective and well-executed automation strategy spend less than 10 percent, which means they have more time to optimize production and tackle other value-adding tasks.

So what is enterprise-style automation? The idea is simple: Data are available to everyone who needs them, both internally and externally, the moment they are captured. This means eliminating the all-too-common practice of gathering data in an unusable form and leaving them there until an extract, translate, and load program can pick them up and convert them.

The goal is to make sure everyone within an organization has access to the latest data. Once that happens, production engineers who used to spend an hour a day calling operators to get the latest data for a well will be able to access the latest data when needed.

With the right information technology security systems, relevant data can even be made available to service companies. For example, a water hauling contractor may be able to access tank levels so it can identify tanks that are ready to be emptied. This eliminates the need for the operator to micromanage the contractor and allows the contractor to use its vehicles more efficiently, creating a win-win situation that ultimately lowers operational costs and risks.

Next Steps

Standardizing and aggregating data creates opportunities for even greater gains. The most important is to manage wells by exception, not by routes. In other words, instead of visiting every well, operators can use software to automatically identify anomalies that suggest a well needs attention. By focusing on these, operators will spend less time behind the wheel, a boon for their efficiency and safety.

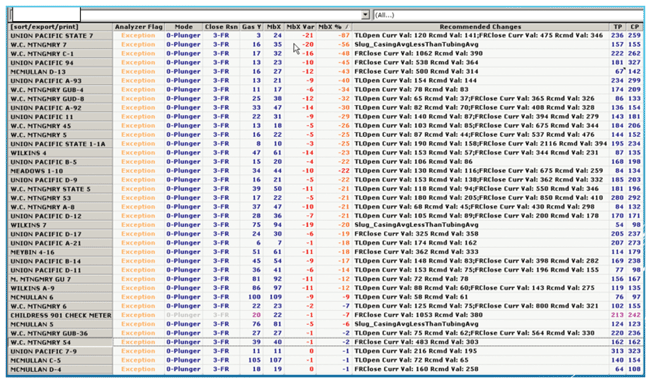

By sorting wells based on the difference between reported and expected values, management by exception software helps operators identify wells that need attention. Focusing on these wells rather than checking every well, ultimately leads to greater efficiency and higher production.

Furthermore, because operators only have to visit a handful of wells each day, they can take care of issues that previously would have to be referred to foremen or managers, such as leaking diaphragms and other simple maintenance. This saves the company money by reducing the number of times crews need to visit a given site.

Companies can gain even more from their automation equipment by creating centralized control and dispatch centers, where experts monitor wells, compressors and other assets to direct activity. Because they are no longer spending hours driving from site to site, a handful of experts can oversee 2,000-5,000 wells.

With so many wells under their supervision, even the best and brightest will need help prioritizing. Fortunately, the same software used to identify exceptions can rank wells by priority. The more sophisticated programs analyze underperforming wells to diagnose problems and suggest solutions, then rank those wells by potential production gains. However, such high-end software is not necessary for big gains. Companies with more modest budgets can rank wells by the difference between expected and actual values (e.g., predicted production and actual production), or by the degree to which values fall outside average values.

To maximize the operational efficiency provided by automation equipment, companies should integrate the control and dispatch center with their human resource systems so dispatchers can send the closest people with the right certifications and skills to handle problems. For example, an operator would send only a Waukesha-certified mechanic to repair a compressor package with a Waukesha engine, or ensure that anyone who works near a hydrogen sulfide-prone well has completed proper H2S safety training. This approach can be defined as “purpose, proximity and skill.”

When the dispatcher sends technicians to a site, the control and dispatch center also should notify them of any open work orders or tickets they might be able to handle. Mechanics originally dispatched to bring a compressor back on line are more than capable of checking spill containment systems and handling other routine inspections. By having them do so, the company will save time and reduce traffic on the roads.

Benefits

Whether a company chooses to stick with managing wells by exception or progresses all the way to purpose, proximity and skill, enterprise-style automation offers numerous benefits. Because employees can identify problem wells remotely and make fixing them a priority, downtime decreases and production increases. Some issues even can be resolved remotely, making a trip down a rough, muddy lease road unnecessary.

Because employees spend less time driving from one place to another, they have more time to optimize wells, which increases production. In a test on 340 wells in South Texas, production increased 35 percent after implementing a well-planned automation strategy. That degree of improvement is rare, but even a more typical 1-3 percent production increase can contribute greatly to the bottom line, particularly for large-scale operations with high numbers of wells and associated facilities, such as resource plays.

As noted, automation also increases the number of wells each employee can handle. This secondary benefit can be significant for an industry facing what appears to be a chronic shortage of qualified and experienced personnel. The increased efficiency gained from automation not only enables companies to grow with fewer staff expansions, but also lets them redirect employees toward activities that contribute more to the bottom line.

At the corporate level, enterprise-style automation has another secondary benefit that sometimes is overlooked: It lets the chief financial officer see production reports more quickly. Because the data behind the reports are available instantly, a CFO no longer has to wait for someone to bring the data back to the office, input them, and prepare the report, which can take two or three days. Since CFOs use daily production reports to accrue money, eliminating that delay can add up to hundreds of thousands of dollars each year.

Because of its numerous benefits, adopting an enterprise-style approach to automation can pay off quickly, even on a relatively small scale. Take a single well recently analyzed. Installing the automation equipment would require a $12,000 upfront capital expenditure, with $75 a month in reoccurring costs for maintenance and communication. The well produces 100 barrels of oil and 300 Mcf of gas a day. If automation reduced downtime by only nine hours annually, or if it enabled the company to increase production by only 0.06 barrels and 1.75 Mcf a day, it would pay for itself, including both the initial and reoccurring costs, within two years.

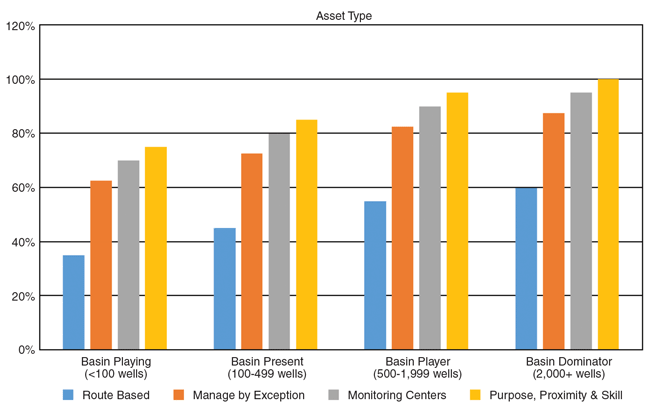

Large operations with well-developed, dense fields and larger economies of scale will gain more from automation than smaller operations. Only the largest companies will unlock automation’s full potential, and even they must use purpose, proximity and skill to do so. However, even much smaller companies can gain most of automation’s benefits as long as they manage their wells by exception, and they, too, unlock more by progressing to purpose, proximity, and skill (Figure 1).

The Barrier

If automation has so much to offer, why do some companies continue to use traditional approaches to checking wells? The first answer is that people naturally trust their own eyes more than a machine. They want to believe that someone who visits each well will identify more problems than an automation system that must rely on preprogrammed rules to do so.

That might be the case if an operator was stationed at each well site 24 hours a day, seven days a week. But in reality, an operator can only visit a well for a very short time, usually once a day, and only checks 10-12 variables on average at each well location.

In contrast, automation systems often gather an average of 24 data points every second. It is hard for even the best operators to compete with 200,000 checks a day on more than twice the amount of data! They are much better off letting a reliable machine handle the data gathering so they can apply their human ingenuity and problem-solving skills to issues the machines cannot handle.

To make that possible, some companies install automation equipment by looking at each project individually, selecting whatever equipment and data management systems seem most appropriate at the time, rather than adopting a comprehensive enterprisewide automation strategy. This leads to a new problem: islands of automation that each store data from different areas and sources.

These islands are fine if a single area and group require the data. But to get the right data for larger projects, employees need to know how each system works and what it contains. Even after they have mastered all of the systems, gathering data from them can be tedious and error-prone.

Enterprise-style automation simplifies data access by insisting that the company use as few systems as possible to hold the data. At the same time, it enforces consistent data naming conventions across all systems and areas, which makes it easier for users to interact with the data. They no longer need to play phone tag with someone who knows the eccentricities of a specific system or tries to deduce what pressure “PR” refers to (if it refers to a pressure measurement at all).

Consistent naming conventions help warning signs stand out. If an engineer sees “-46” next to tubing pressure, he will know immediately that the -46 is an error and start figuring out what is wrong. But if he sees the number next to a poorly-named data element, such as “T,” he has to figure out whether that is a valid number, as may the case if it is a temperature on a chiller tower.

The conventions also make combing through the data with software easier, because the underlying code no longer has to be adjusted to accommodate for differences from system to system.

In its purest form, enterprise-style automation also involves adopting one or two brands for each type of equipment, and minimizing the number of configurations deployed to simplify training and maintenance. Coupled with consistent data naming conventions, this reduces long-term deployment and maintenance costs.

However, because enterprise-style automation requires planning and discipline, it has a higher upfront cost than the traditional “project by project” approach. As a result, many companies stick with that approach until the islands of automation become unmanageable. When they finally decide to switch, they have to wrestle with integrating legacy equipment and data into new systems and convince old hands to change long-established work habits.

Such change can be easy for executives and managers, whose jobs frequently involve looking at the bigger picture and the bottom line. But the frontline employees who will be responsible for implementing, maintaining and using the enterprise-style automation approach will be far more likely to balk at the changes it will require in their daily routine.

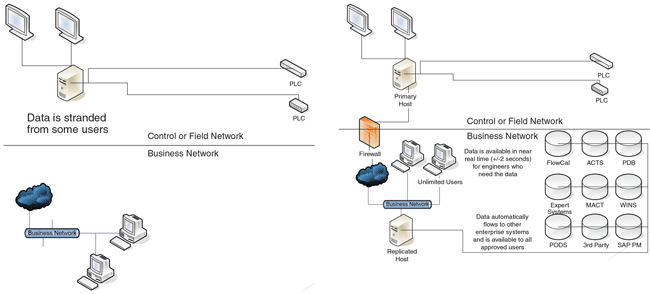

In the traditional approach to automation (left), data are held in separate systems or “islands of automation.” As a result, employees spend considerable time exchanging, translating and verifying data. In contrast, the enterprise automation approach (right) makes data available to all authorized users simultaneously and automatically exports data to key software programs. This enables employees to concentrate on analyzing data, making informed decisions, and increasing production.

An executive could ignore those employees’ reluctance and mandate a change, but the process will go much smoother if most of the people involved believe it is worthwhile, so it is usually wiser to get almost everyone onboard with the new approach. The executive could get that support by going from place to place and talking with employees in an attempt to gain consensus, but that would be so time-consuming the technology originally proposed would be outdated before enough support had been gathered.

Instead, an automation advocate should identify the internal and external stakeholders who will need to buy into enterprise-style automation for it to be successful, talk with each group to learn about problems they have every day, and solve those problems through automation. By doing so, the advocate will build a cadre of cheerleaders who can say from personal experience that the benefits of automation are worth enduring a little change.

With enough support and need, even large companies can switch to enterprise-style automation quickly. Implementation times range from two months to five years, with the exact time depending on the organization’s desire for change and the number of systems that need to be consolidated.

Software Selection

Although it is possible to make almost any data repository work for enterprise-style automation, it is simpler to implement and maintain if the company finds one that can enforce data naming conventions. This is vital to ensure that both humans and the anomaly-finding algorithms interpret the data correctly.

The software should also make it easy to share data throughout the organization and with select business partners. That means it needs to have enough security features and settings that the partners only see the data they need.

Because operational datasets become quite large with time, the software should be capable of segmenting data. The engineers in the Permian Basin office, for instance, need to be able to download the subset of data that is relevant to them so they do not overload the company network making data requests or waste processor time combing through data from other regions.

Finally, the software should provide a clear and easy-to-use interface. Ideally, it should direct the user’s attention to problems or opportunities with minimal fuss. Because blinking lights and animation can be easy to ignore after only a short period, a minimalist interface often works best. Shadows, 3-D pictures, and other bells and whistles may look impressive during a demonstration, but remember, the software exists to inform, not to entertain.

When evaluating software, keep in mind that human evolution has given even the most highly trained and intelligent individuals a set of biases. For example, we often assume that size correlates with importance or threat potential, so if a diagram shows two tanks, we will subconsciously pay more attention to the larger one, even if it is within perfect operating parameters.

Size bias can show up in more subtle ways. For example, I have often seen companies use “off” to indicate that a pump is not running but “pump 7 is running” to indicate it is on line. Because the second message is so much longer, it will draw the eye more than the warning that a pump has gone off line, even though that is of greater concern.

If possible, the people who will be using an interface should evaluate it, because they might interpret it differently than a generalist. Consider the common practice of using red to highlight a problem, yellow to indicate a potential problem, and green to show that everything is fine. Because we are all familiar with traffic lights, it is easy to think these colors’ meaning will be clear to all.

Using management by exception software at control and dispatch centers enables operating companies’ experts to oversee 2,000-5,000 wells. To maximize efficiency, these centers should integrate with human resource systems so dispatchers can access certifications and other information that will allow them to send the best person for each job.

That is often, but not always, the case. For a processing plant engineer, green merely shows that a system is running within acceptable parameters. For an electrical engineer, green may indicate that the system is not energized and safe to work on, not that it is running. Those associations can be hard to ignore, so it is vital to have the technical experts choose an interface look and feel that makes sense to them, even if it seems less effective to outsiders. In this context, sometimes managers should be considered “outsiders!”

Hardware Selection

When selecting controllers, it is often tempting to buy the most flexible and powerful equipment. But for most applications, highly configurable, not programmable equipment will suffice. By using these controllers instead of their more complex brethren, operators can minimize installation, training and maintenance costs.

When deciding whether to use programmable logic controllers (PLCs) or remote terminal units (RTUs), the application must be kept in mind. If it demands a proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controller loop that is faster than 250 milliseconds, a safety integrity level, or 250 inputs and outputs, a PLC might be appropriate.

In applications that call for well control, an RTU usually works better. A modern RTU can have 24,000 plunger lift well control combinations already coded in it. A PLC could support the same combinations, but programming them would take considerable time. RTUs also have the advantage of being robust enough to survive without an environmentally controlled enclosure in most areas, and can rely on solar power.

When deciding whether to install redundant automation equipment, consider conducting a single point-of-failure survey, which involves listing all the equipment that does not have redundancy on a site and estimating how likely it is to fail. For example, many sites include generators that cause all the equipment to go down if they fail. If the generator accounts for 95 percent of the site’s downtime, the company would gain little from redundant RTUs or PLCs.

Companies should also estimate their “mean time to repair,” or how quickly they would respond to a given failure or event. They can do this by imagining what they would do if they learned that a piece of equipment had gone down at 3 p.m. If they would immediately dispatch someone to bring it back on line, the automation equipment needs to be more reliable and capable of communicating issues quickly. If the operators would instead wait until the next day to address the problem, the automation equipment can be less robust and only needs to communicate periodically.

These cost-versus-benefit analyses are more important than ever. Many fields call for multiwell pads, which require more complex infrastructure and a greater degree of well site automation than single-well sites. As a result, the cost for automating each pad site has risen.

As wells and pads become increasingly complex, the quantity of automation equipment on each site, the amount of data gathered, and the complexity of the analyses required to use those data will continue to trend sharply upward. Companies that take the time to develop enterprisewide automation strategies not only will increase their short-term productivities and profits, but also willprepare themselves to scale up as their footprints expand.

DAVID WRAY is the president of NuPath Consulting, an automation consulting specialist based in The Woodlands, Tx. During his 35-year career, he has developed expertise in automation strategies and equipment, SCADA assessments, project management, and big data. Before founding NuPath, he served as automation manager for Anadarko Petroleum Corp., and prior to that, as project management and SCADA manager for Burlington Resources. At both companies, Wray played a key role in developing and implementing automation strategies to increase efficiency and production.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.