Technologies, Trends Driving New Automation, ‘Intelligent’ Field Capabilities

By Fred Czubba

OTTAWA, ONTARIO–Imagine five decision makers sitting in a centralized operations center, leaning into real-time displays of field sensor data, predictive models and financial information. Operations personnel stand by for a coordinated response. A computer system provides expert guidance, representing the collective knowledge of reservoir engineers, production operators, automation engineers and optimization specialists. Multiple response scenarios are analyzed in the span of a few minutes with the aid of artificial intelligence and integrated data modeling. A decision is reached. Action is taken.

This is the future of the intelligent field.

The oil and gas industry is in a position to gain great advantage by applying intelligence throughout all operations. This process is already under way, with automation logic, communications networks and analytics being employed on some equipment to solve problems in the field. Multisensing smart sensors in the field provide additional levels of information. The next great move forward will come with the application of technology and human knowledge combined in expert systems. The opportunities will be tremendous for efficiency, production, safety, environmental protection and recruitment.

Of all the opportunities for automation, efficiency is usually where the conversation starts. Automation has been applied to reduce the number of workers required to run rigs or inspect wells. In tight oil and shale gas plays, it has helped remove redundancy in multiwell pad equipment control. Yet these gains only scratch the surface of the opportunities now available. Expert systems and artificial intelligence already are providing benefits to upstream operations and will become ubiquitous as the industry responds to significant operational and business pressures.

Two Major Issues

From a high-level perspective, there are two major issues facing the oil and gas industry. The first has to do with people. The second has to do with adapting to what may be the new normal of lower commodity prices. Automation and expert systems, in particular, can help solve both of these big challenges.

The people problem has been a long time coming. Way too much of the workforce is approaching retirement without replacements slotting in behind them. Transferring their wealth of experience to the next generation is a serious challenge that grows every day. No matter how many talented young people enter the oil and gas industry, decades of experience are at risk without a new approach.

Meanwhile, predictions are that the industry will require 30,000 new workers every year for the next five years. The industry simply is not on track to achieve that. A recent graduating class of process automation engineers illustrated the problem. These students were interested in working with electric cars, solar and advanced manufacturing. None of them, however, planned to enter the oil and gas industry. Not even the promise of six-figure incomes seemed to draw these bright, fresh minds. In fact, according to a recent Accenture report, only 2 percent of college graduates view the oil and gas industry as a viable employment option.

A dramatic shift is required to change perceptions of the industry. New workers of all kinds expect technology to be part of their everyday work experiences. They want to be socially responsible and have interesting jobs from the start of their careers. Using expert systems in everything from training to maintenance, reservoir engineering, geophysics, drilling operations, production and economic analysis presents a real opportunity to attract a new young talent pool.

As for the second issue, sustained lower commodity prices since late 2014 have forced oil and gas companies to reconsider the old strategy of “drilling their way to profitability.” Efficiency has become the watchword. And indeed there is some opportunity for quick cost-cutting. Operators are pursuing automation strategies that aggressively can eliminate nonproductive time and unnecessary costs from an increasingly lean system. These operators stand to save millions in each major facility, given that typically 4 percent of lost production is caused by equipment downtime.

Automation is the foundation for optimizing processes. The ultimate goal is to maintain the lowest lift price with the highest achievable efficiency. Huge investments have been made in measurement devices, communications infrastructure and control equipment to advance this goal. The result has been highly complicated systems that require significant care and feeding. An average field generates more than 1 petabyte of data every day. Expert systems can help codify rules for handling this information and enable faster decisions to shrink costs and risks while expanding production. They also can self-monitor and gather feedback from experts around the world.

Automation Requirements

All across the oil and gas fields of North America, there are trucks on the road. In fact, one company clocked more than 10 million miles last year in one large oil field alone. Deploying automation in producing fields can reduce windshield time, increase efficiency and improve safety. Together, advanced automation, wireless technology and digitalization can increase efficiency by 3-5 percent. That level of efficiency gain is within every operating company’s reach.

The dominance of horizontal tight oil and shale gas plays has changed the configuration and concentration of the typical upstream operation. Now, most wells are drilled on multiwell pads, which have dramatically improved drilling, well completion and production efficiencies. The close proximity of power, pumping, separation, storage, piping and communications on pad sites is an advantage for routine control and maintenance, but also can be problematic when things go wrong. The cost of an outage is very high when equipment is concentrated in a small area. Additional layers of automation and control must be considered to ensure trouble-free equipment “uptime,” operational safety and environmental protection.

Requirements for automation systems are clear. New technology must fit into existing infrastructures using standardized interfaces that enable compatibility. Reporting and even customization must be information technology-independent. Systems also must support mobile and offline work, presenting data in personalized dashboards for easy comprehension.

Similarly, the goals are clear for upstream operational improvement. Intervention must be exception-based, with no unnecessary pad or equipment site visits. Systems must focus on preventive measures and support a faster response to downtime. More acreage should be covered by the same staff size, with priorities set based on production levels. Overall, there should be greater visibility to the entire process and better information to guide decision making.

A typical upstream operation now includes optimization, automation and higher-level control deployed at large numbers of well sites, production centers or centralized facilities, and oil and gas terminals. Virtually everything can be optimized, including well models, multiphase flow models, artificial lift, well tests, mass balancing, separation, movement, blending, planning and scheduling. Disparate devices can be connected through supervisory control and data acquisition integration and tracking, and allocations and analysis can be automated. Transaction processing, abnormal situation event management and process diagnoses are managed through high-level controllers.

Overall, key automation trends should not be surprising. Expect heavy and continuing adoption of intelligent devices, wireless technology, asset management, and remote monitoring, control, diagnostics and maintenance. These technologies provide a continuous flow of data from wells for real-time analyses to identify problems before they can occur and address them as needed, including by remotely shutting down wells if necessary. Wireless technology at the pad site enables real-time surveillance and control, complete with diagnostics, alarms, trip points, notifications, performance tracking and reporting.

Intelligent Oil Field

The digital oil field already exists. Now the ingredients for the intelligent oil field are available for oil and gas companies to put to work. Chief among these are big data, computing power, technical domain expertise and artificial intelligence.

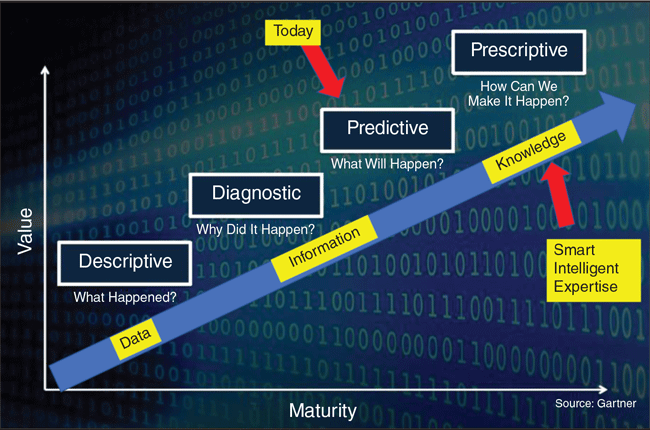

One way to look at the state of upstream data is from a maturity model perspective (Figure 1). Industry data’s value increases with maturity. At one time, data were simply descriptive, relating what had happened. Over time, data became more diagnostic, explaining why something happened. At that point, the data had become information. Next came the predictive stage, where information began to describe the probabilities of what could happen at some point in the future.

Finally, and in its most useful form, information becomes knowledge and its value is prescriptive, describing how to make something happen. This is where the intelligent enterprise emerges. The industry now is approaching this level of data maturity, and can leverage intelligent workflows with prescriptive outputs with the extraordinary computing power available today at low cost.

The intelligent oil field integrates data with work processes, expertise and technology to drive quicker and smarter decisions, efficiency gains, production optimization and improved risk management. It captures knowledge that otherwise is lost when people leave an organization for whatever reason. It leverages technical domain experts, including those with decades of experiences who have learned from previous successes and failures in specific fields, reservoirs or operations.

In considering the specific capabilities an expert system could bring to field operations, one practical example would be managing one of the industry’s longest-standing and costliest problems: produced water. One of the holy grails in oil and gas production long has been the ability to practically and affordably separate water down hole so that only hydrocarbons come to the surface. Expert systems could be the key to enable reliable downhole water separation, automatically adjusting to changing reservoir conditions to continually separate and reinject water into a nonproductive zone.

Production would be optimized and there would be less surface equipment, less corrosion, and less complicated piping, storage and transportation logistics. The reservoir even may benefit by experiencing less dramatic fluid volume changes. This scenario is realistic and likely in the future. It is a natural progression from today’s automation to tomorrow’s expert systems. It also is the kind of technological project that may help inspire a new generation of process engineers and computer scientists.

Expert System

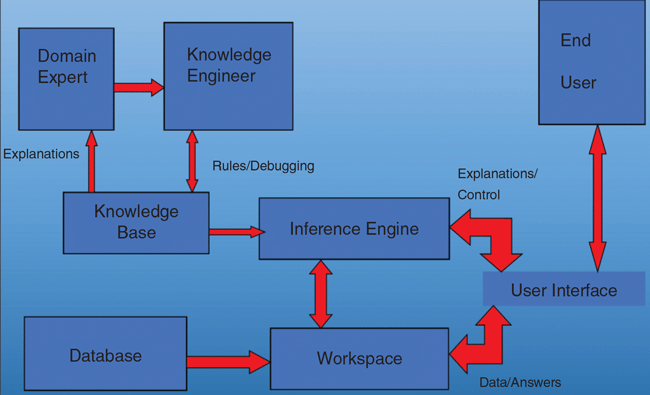

Building an expert system (Figure 2) begins with domain expertise that is painstakingly gathered and engineered into a knowledge base. Both the expertise and the engineering are critical to achieving a meaningful output.

Knowledge is input into expert systems as a series of rules or patterns that can be recognized. There may be hundreds of rules defined, derived from the input of hundreds of experts, from earth scientists to drilling engineers and production operators. Rules also can be driven from data and models, such as reservoir models and well production profiles.

Like humans, computers have the ability to reason. Humans usually reason using specific rules, categorization, heuristics, past experiences and expectations. Computers have no expectations. Instead they reason based on defined rules, frame concepts, cases, pattern recognition, neural networks or generic algorithms.

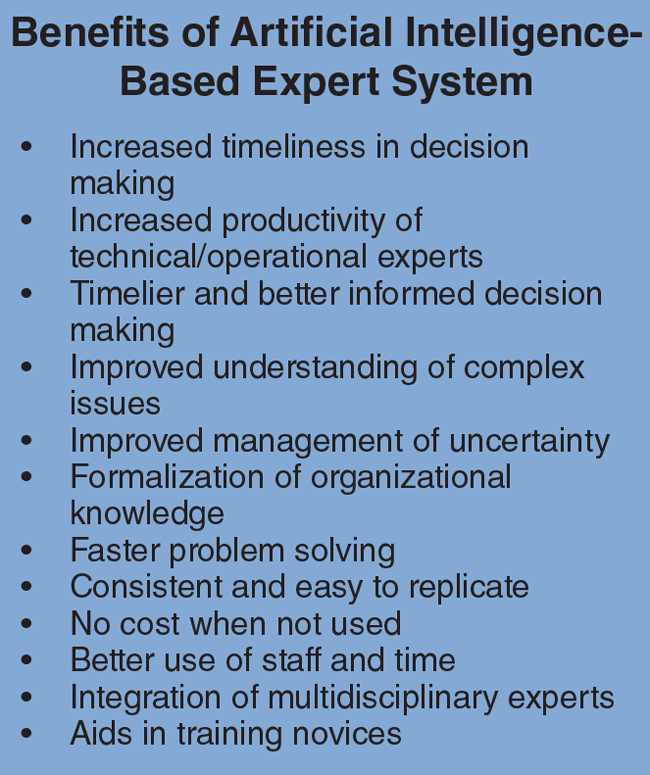

Consistency is one of the quickest benefits of expert systems, as they formalize knowledge. Some of the most mundane tasks can be transferred to expert systems, standardizing the work and freeing people for higher-value activities.

Technology is not the biggest hurdle in establishing expert systems, nor is budgeting. The biggest issue is extracting knowledge from experts. Expertise is difficult to capture. There is an art to gathering meaningful and complete answers, beginning with asking the right questions. It is also critical that knowledge gaps be identified and filled. Sometimes, the knowledge is simply not available.

Expert systems already have been deployed successfully in oil field applications, including fault diagnosis, process hazards review, emergency response, chemical spill response and maintenance scheduling. These applications illustrate the breadth of benefits that come from this next level of automation (Table 1).

The first and most obvious benefit is efficiency. Well-trained machines can make better, faster, more consistent decisions than humans. For example, in field maintenance, an expert system can monitor thousands of sensors and other input devices, look for patterns and identify potential problems before the pumper drinks his first cup of coffee. The pumper is then free to focus on those wells that truly need attention.

Similarly, expert systems can use data from the well, equipment manufacturers, other similar wells, global positioning systems and production operator rules to recommend the most efficient preventive maintenance schedule. Field personnel log less windshield time and spend less time waiting for parts. Just about everything and everyone can become more efficient with expert systems.

Interestingly, wells also can become more productive with expert systems. First, production can be increased by reducing or eliminating downtime. Second, fine-tuning every aspect of production operations can result in overall productivity increases. When expert systems are combined with four-dimensional virtual operation centers, they enable sharing and synergy of efforts. Decision makers in the center receive ultrafast expert recommendations and can run fast alternative scenarios. Operations people in the field can take immediate action, enabling optimal production.

Another great opportunity is in the area of safety. When expert systems enable remote monitoring and control, they reduce miles driven and the number of site visits, decreasing the risk of accidents or worksite incidents. Training is improved and maintenance can be streamlined. In addition, expert systems can detect and shut off leaks faster than possible with human intervention. They even can identify conditions that may lead to leaks and avert an environmental problem before it can happen.

Most remarkably, implementing the intelligent oil field presents the opportunity for renewing young workers’ interest in the industry. This recruitment tool should not be underestimated. Expert systems optimize, engineer, operate and control operations at an entirely new level. Coupled with a trend toward better environmental stewardship, these systems will play an important role in recruitment and retention in the years to come.

Fred Czubba is founder and president of Ottawa, Ontario-based AXE Consulting Ltd. He began his career in 1974 as a commissioning engineer at ABB Lummus, and worked for the company for 26 years in project management and senior business development positions. Czubba also previously served as a regional manager at Siemens and as senior business development manager of oil and gas, refining and petrochemicals at Phoenix Contact. He is a graduate of Lambton College of Applied Arts & Technology, Worcester Polytechnic, and the Thunderbird School of Oil & Gas Management.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.