Dallas Fed Report: Don’t Blame Industry For High Gasoline Prices

WASHINGTON–U.S. oil producers cannot arbitrarily choose to lower gasoline prices, argue economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

In analysis the Dallas Fed published in May, Garrett Golding, a senior business economist in the Dallas Fed’s research department, and Lutz Killan, a senior economic policy adviser in the same department, cite the size of the global oil market and the influence of world events in driving consumer energy prices. They also warn that piling new regulatory requirements on oil companies is unlikely to help the situation.

The report notes that historically high U.S. retail gasoline prices are triggering debate about whether U.S. oil companies are doing enough to rein in prices and whether these companies should be held accountable for not increasing crude oil production. After considering the premises underlying this debate, the report concludes, “even though the price of oil makes up over half of the retail price of gasoline, oil companies play an extremely limited role in how retail gasoline prices are set.”

U.S. retail gasoline prices have remained stubbornly high throughout the country since March, but this situation reflects frictions in the retail gasoline market rather than the supply or price of oil, the report assesses. Noting that many regions’ pump prices have not fallen as quickly as oil prices, a trend some industry critics cite as evidence of price gouging, the Dallas Fed piece explains why such asymmetry is not necessarily an indication of price gouging.

The analysis also examines the obstacles to substantially increasing U.S. oil production, and makes the case that even under the most favorable circumstances, higher production growth is unlikely to materially lower global oil prices–and, thus, U.S. retail gasoline prices–in the near term.

A Complex Supply Chain

“Before a gallon of gasoline is pumped into a car’s tank, it has traveled through a complex supply chain,” the Dallas Fed observes. “Independent oil and gas companies–those without refining assets–are responsible for 83% of U.S. oil production and about half of the oil consumed in this country. Oil is sold in competitive markets at prices reflecting global supply and demand. It is refined into gasoline, diesel and other fuels whose prices are similarly set in competitive markets.”

From there, the report describes, fuels are sent to more than 400 U.S. distribution facilities, where they are sold and delivered to retailers and end-users at another price depending on local conditions. “Gas station operators set retail prices based on their expected acquisition cost for the next delivery of fuel from the local distributor, federal and state tax rates, and a markup that covers operating expenses, such as rent, delivery charges and credit card fees,” it explains. “Since only 1% of service stations in the United States are owned by companies that also produce oil, U.S. oil producers are in no position to control retail gasoline prices.”

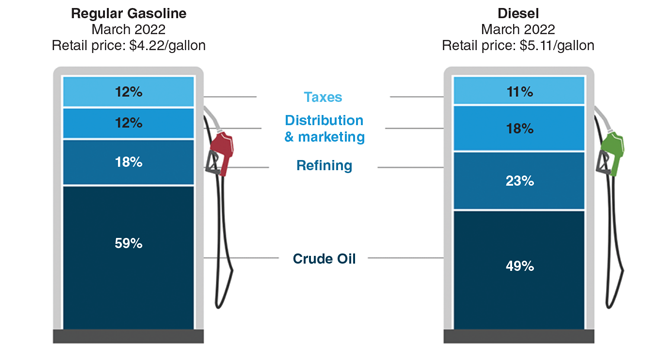

To convey the relationship between oil price shocks and retail gasoline prices, the Dallas Fed cites data from the Energy Information Administration that breaks down the average proportional costs associated with a gallon of gasoline and diesel fuel (Figure 1). The report acknowledges that much has been made of the fact that gasoline prices rose much quicker following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine but did not subsequently drop at the same rate as crude prices.

FIGURE 1

Proportional Costs In a Gallon of Fuel

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, Gasoline and Diesel Fuel Update

“Given that crude oil accounts for 59% of the cost of gasoline, a 34% increase in the price of oil should imply a 20% increase in the retail gas price,” the report considers. “Likewise, a 22% decline in the price of oil should translate to a 13% decline in the pump price. However, that did not happen at the national level.”

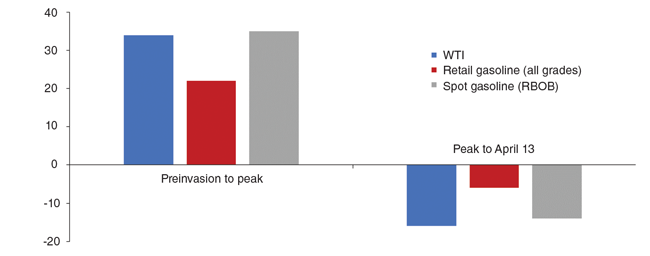

As Figure 2 shows, the spot price of gasoline (the price of gasoline at the refinery gate), as proxied by the prompt contract for New York Mercantile Exchange RBOB gasoline, generally rose and fell with the price of West Texas Intermediate crude oil, the analysis notes. “However, the response of U.S. pump prices has been highly asymmetric,” it observes. “While the price of retail gasoline cumulatively rose about as much as expected following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, recent national retail gasoline prices dropped only 6% from the March peak, far less than the expected 13%.”

FIGURE 2

Cumulative Price Changes

Notes: Bars represent the cumulative percent change in the domestic spot market price for West Texas Intermediate crude oil, retail regular gasoline (all grades) and spot gasoline reformulated blendstock for oxygenate blending (RBOB). “Preinvasion” indicates the price on Feb. 23, 2022; “Peak” indicates the price on March 8, 2022, for WTI and wholesale gasoline and March 11, 2022, for retail gasoline as the two had different peak dates.

Sources: Energy Information Administration; Haver Analytics

The upshot, the Dallas Fed indicates, is that lingering high retail gasoline prices were not a product of an oil shortage or high oil prices. Instead, it says, elevated retail gasoline prices must be attributed to the U.S. retail gasoline market.

“Moreover, the asymmetry of the response of retail gasoline prices need not be evidence of price gouging,” the report maintains. “One potential explanation is that station operators are recapturing margins lost during the upswing, when gas stations were initially slow to increase pump prices. The reluctance to lower retail prices also likely reflects concerns that oil prices–and, hence, wholesale gasoline prices–may quickly rebound, eating into station profit margins.”

The asymmetry also may stem from consumers’ tendency to seek lower pump prices more intensely as gasoline prices rise than when they decline, the report adds. “This diminished search effort provides further pricing power to gas stations, causing prices to fall more slowly than they rose,” the analysis says. “This has prompted researchers to liken the response of gasoline prices to higher oil prices to a rocket–and the response to lower oil prices to a feather.”

One other potential explanation for such asymmetry, it suggests, is that seasonal demand tends to increase as the weather warms, supporting higher retail prices.

Regional Differences

Retail gasoline prices have not behaved uniformly across the country, the report observes, Dallas retail prices fell at a pace that indicated a symmetric price adjustment.

Phoenix prices, in contrast, remained virtually the same as they were during the March 10 national retail average peak.

“In the case of Phoenix, which is served by Southern California oil refineries, an unexpected refinery outage in early March prompted higher regional wholesale fuel prices just as prices elsewhere in the country started to fall,” the Dallas Fed points out. “This suggests that price-reduction policies that treat all regions of the country the same are unlikely to be effective at curing the root causes of the asymmetry in the aggregate retail price response.”

Obstacles To Output

“Consumers and policymakers often ask what domestic oil producers can do to raise output and lower gasoline prices, especially since producers’ profitability has greatly improved in 2022,” the Dallas Fed describes. “Because the price of crude oil is determined in global markets, increases in domestic oil production affect the retail price of gasoline only to the extent that they lower global oil prices.”

The analysis then examines a talking point frequently raised by policymakers and public voices: The industry has so many permits to drill on public lands that it cannot claim its hands are tied by constraints on public lands leasing and permitting. Such assertions do not hold up under scrutiny, it assesses.

“Many observers point out that oil companies currently hold nearly 9,000 permits to drill on federal lands. But holding 9,000 permits does not equate to 9,000 well locations that are worth drilling, nor would it be possible to churn through that much inventory in a reasonable time frame,” the Dallas Fed explains. “Data provider Enersection found that since 2015, an average of 1,560 wells have been drilled on federal lands annually, but only 47% of federal permits issued were actually utilized. This is because companies tend to acquire permits on the acreage they lease even if they are not certain whether the location is worth developing.”

According to the report, data from the most recent Dallas Fed Energy Survey suggests investors’ preference for capital discipline–which discourages expanding oil production–is publicly-traded companies’ primary restraint on new activity. “This is not simply a case of investors being selfish, but of investors who suffered persistent losses in years past wanting compensation for the risk they take,” the report says. “Depriving these investors of the returns they insist on, by whatever means, would likely be counterproductive because without these investors, the industry would lack the capital to maintain–never mind, increase–crude production going forward.”

Moreover, the Dallas Fed observes, producers and service companies have faced labor shortages, rising input costs and supply-chain bottlenecks for vital equipment such as well casing and coiled tubing. “An industry that lacks experienced staff and materials cannot on short notice substantially increase drilling and production,” it says. “Complicating matters, many shale producers are running low on top-quality drilling locations. Thus, it would be unreasonable to expect a noticeable increase in oil production before 2023 at the earliest, even if investors were to agree to higher production targets.”

If the challenges to expanding domestic production vanished and output rose, the effect on prices would be minor, the report argues.

“Even under the most optimistic view, U.S. production increases would likely add only a few hundred thousand barrels per day above current forecasts,” the Dallas Fed calculates. “This amounts to a proverbial drop in the bucket in the 100 million barrel a day global oil market, especially relative to a looming reduction in Russian oil exports due to war-related sanctions that could easily reach 3 MMbbl/d.

“Placing the responsibility to lower retail gasoline prices on shale oil producers is thus unlikely to work, and additional regulation of oil producers is unlikely to lower pump prices,” the report concludes.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.