Long-Term Contracts Remain Elusive In Power Sector

By Gregory DL Morris, Special Correspondent

HOUSTON–Natural gas-fired plants are projected to account for about two-thirds of total U.S. electric generating capacity additions through 2040, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. The EIA’s forecast calls for gas demand in the power sector to grow at an average rate of 1.6 percent annually, expanding the market share for natural gas from 24 percent of total generation expanding in 2011 to 30 percent by 2040.

Relatively low capital costs and dramatically improved emissions profiles give natural gas major advantages over coal for building new generation capacity, and the power sector’s shift away from coal in favor of natural gas has been further driven by the economics of low commodity prices and abundant gas supplies. However, in its Short-Term Energy Outlook issued on Aug. 6, EIA points out that average spot natural gas prices increased 40-60 percent during the first half of 2013 compared to the same period in 2012. Despite price declines over the past couple months, EIA projects that prices will remain substantially above 2012 levels through the end of the year.

Producers, consumers, and industry analysts alike note that one notable factor is missing from this happy scenario of rising production and rising demand: long-term contracts. Earlier this year, when Chesapeake Energy signed a 10-year deal to supply Methanex Corp. gas for its massive new methanol complex near Geismar, La., analysts covering both publicly traded companies hailed the contract as a model. The exact terms were not disclosed, but the companies reported that a pricing mechanism had been crafted based on the costs of raw materials and delivery, as well as finished products.

With increasing spot prices (the spot price at the Algonquin city gate serving Boston rose to $8.09 an MMBtu on July 16, while on the same day natural gas futures were trading in the $3.70 range on the New York Mercantile Exchange), it would seem logical for power generators to begin seeking longer-term arrangements with gas suppliers. However, while there are some long-term supply contracts between producers or distributors and power generators, the majority of utilities continue to buy on spot or short-term arrangements.

What prevents public utilities from securing gas supplies by entering long-term contracts? The reasons vary from financial to regulatory, according to Joe Nipper, senior vice president of government relations at the American Public Power Association. There are about 2,000 public power utilities around the country owned by local governments or rate payers serving 47 million customers. While most utilities own generating capacity, almost all of them buy power on the commercial wholesale market, he notes. “They prefer long-term contracts for their power, and also prefer long-term contracts for their fuel,” Nipper states.

It would seem natural for the public power sector and gas suppliers to make common cause with long-term contracts, but Nipper explains there are several structural, financial and regulatory complications. Those include the utilities’ capitalization that may not support such arrangements, public utility commissions that may look with disfavor on financial obligations of that nature, and also the complex partial deregulation and restructuring of the national power market.

“We have had deregulation in areas of the country where electricity rates were high, such as the Northeast, Middle Atlantic, Midwest and California,” Nipper remarks. “In those regions, the independent system operators (ISOs), also known as regional transmission organizations (RTOs), operate the grid and buy power. In other parts of the country, there has been a wait-and-see attitude about restructuring. That bifurcation continues. About half the states have implemented retail competition or engaged in divestiture of generating capacity. Our members have opted out of that.”

Nipper encourages gas suppliers to engage with utilities, but to be flexible and realistic about working with a wide variety of companies in an evolving regulatory and financial landscape. “People at every level are grappling with this, from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to municipal officials. We will provide whatever level of service we have to. Our members are willing to do it,” he says.

Large Utility Perspective

For large commercial utilities, their gas suppliers are significantly less capitalized than they are, which means long-term contracts could leave too much operational and financial risk on their side of the table. That position was made clear by Thomas A. Fanning, chairman, president and chief executive officer of Southern Company, not only one of the largest utilities in the country, but also one of the most diversified in its fuel choices.

Fanning pointed out that more than 95 percent of new U.S. electricity generation built since 1995 has used natural gas as the primary fuel source. He said that the natural gas industry is in the midst of a revolution enabled by technology innovation. Over the past 6 years, Southern Company has increased its use of natural gas from 16 percent to 45 percent of total generation, becoming the third-largest consumer of natural gas in the United States and saving customers more than $1 billion in 2012 alone. However, Fanning said major utilities still harbor reservations about the stability of gas pricing and supply.

“The electric utility industry is one of the most capital-intensive industries in America. The normal economic horizons [for new generating capacity] are often 30 years or longer. While natural gas appears plentiful and inexpensive today, there are many variables that could influence its attractiveness over the long term. So while natural gas is a dominant solution, it is only one part of a diversified portfolio,” Fanning stated.

Fanning cited five important concerns in the gas supply equation from the perspective of a major utility. The first is that the gas bonanza is based on hydraulic fracturing and the need to “successfully resolve environmental concerns associated with fracturing.”

Fanning’s second reservation is that “we need to continue to develop America’s natural gas infrastructure, namely interstate pipelines and underground storage. The new sources of natural gas are not located in the same areas as the conventional resources to which we have grown accustomed over the years. Our existing pipeline capacity will have to be expanded. If you consider the fact that more than 50,000 megawatts of coal are expected to be retired or converted to natural gas by 2015, this process must be expedited.”

An equally important infrastructure concern for Fanning is the need for additional gas storage capacity. “Our storage capability is subject to geologic limitations, so capacity growth must keep pace with natural gas consumption,” he stated.

The third potential issue with natural gas, said Fanning, is concern about the pace and degree of exports in the form of liquefied natural gas. Fanning suggested that the net effect of exporting lower-priced U.S. LNG over time “could be to harmonize worldwide prices.”

Noting that current U.S. natural gas consumption is about 67 billion cubic feet a day, Fanning said, “If we export 13 Bcf/d, incremental demand grows by 10 Bcf/d to generate electricity, and another 12 Bcf/d is used for industrial processes and transportation, natural gas demand could rise to more than 100 Bcf/d by the end of the decade.”

In his last point, Fanning looked at the question of long-term supply agreements through the prism of financial risk. “Southern Company’s financial integrity ranks among the best in our industry. For the United States to take these important steps forward for natural gas, we need a similarly viable, financially strong natural gas industry so that suppliers and customers have the ability to manage supply, price and volatility effectively and efficiently over time,” he stated, noting that a risk mismatch inhibits utilities’ ability to enter into long-term price and volume contracts.

All of those five issues notwithstanding, Fanning remains “a huge believer in natural gas.” He concluded by noting, “Taken together and depending on the resolution of these variables, the price and volatility of natural gas could change dramatically. Once again, this underscores how vital it is that our energy portfolio be a diverse one; that we use every resource at our disposal, rather than excessively relying on any single one.”

Producer’s Viewpoint

Looking at it from the producer’s viewpoint, Teri Viswanath, director of commodity strategy at BNP Paribas, says it behooves independents to secure long-term contracts for their gas. “Producers have to care about this on a strategic level,” she states. “Who is going to fund the continued drilling and development? The cash flow is not there, the cheap interest rates will not last forever, and the open funding from joint ventures may dry up. The majors have paid their steep reentry fees to get in U.S. shale plays and most of the known plays are leased up. The industry still has a huge capital funding gap. That should come from gas consumers. They have benefited from the shale boom, and they have a vested interest in seeing it continue.”

Viswanath notes that nearly $100 billion worth of industrial expansions has been announced in the United States to date, with much of it based to one degree or another on plentiful and affordable natural gas supplies. On the surface, the logic seems clear. “They already have the physical gas exposure, why should they not try to lock in a price?” she posits.

To explain, Viswanath says, “Independent producers have lived through half a decade of low prices for natural gas, but the power sector has lived through a full decade of low prices for its product. In most areas of the country, generators are not getting paid for their capacity. Utilities are not signing up for firm pipeline capacity in many cases because they cannot, even if they want to.”

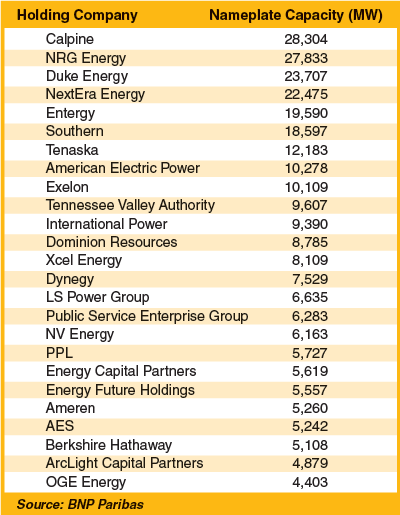

Viswanath relates that Southern Company’s position is certainly valid, but is limited to a few of the largest power groups. “It is true that the gas producing base is very fragmented and there are many small companies selling gas,” she states. “In some respects, the two industries are mirror images of each other, with a few very large companies and many small ones.”

Given the limits of physical assets and geography, it can be difficult for the same-sized companies in the two industries to work with each other on a relatively equal footing. “In terms of numbers of generating companies, most power producers do not have the balance sheets to sustain long-term contracts. Also many retail consumers have heard about the shale gas revolution and expect lower electricity rates because they know utilities are switching to gas.”

Because both the bases of sellers and the buyers are large and disaggregated, Viswanath points out that the risk mismatch that Southern Company’s Fanning cited cuts both ways. “The larger buyers have credit concerns about the smaller sellers. Fair enough. But we have already seen cases where small utilities have had to take write downs on underwater hedges. We have also seen a sequence of municipalities that got their hedging wrong,” she remarks.

Viswanath goes on to note that large gas marketers could serve as intermediaries, but some of those entities have had their own credit or operating challenges, and with partial deregulation, their relationships to power generators and retail utilities can be fraught.

It comes back to the big generators, Viswanath concludes. “Who is too big and who is too small? The largest installed power capacity is now gas. What is the best economical use of that asset? Gas producers need to identify the major buyers in each demand sector and assess the appetite for risk management among those big buyers.”

Table 1 lists the 25 largest holding companies for U.S. natural gas-fired electric generation capacity as ranked by BNP Paribas. This group operates 57 percent of all gas-fired units.

The Reliability Factor

While power generators have been switching their plants from coal to gas at a rapid rate, the switch in mindset is occurring more slowly after so many decades of coal dominating the electricity generation fuel mix. “Coal has some genuine advantages,” says Anthony Sweet, senior energy analyst at Bentek. “Most notably, the reliability of coal is unrivaled. Power company executives and plant managers can look out their windows at huge piles of coal and know they have 30-45 days of fuel right there on their property.”

In contrast, Sweet says gas interruptions can and do happen. “They are not common, but there have been a few,” he comments. “Gas-fired plants have not generally signed up for firm commitments on pipelines, so they bear some responsibility, but electrical utilities are in the reliability business. When the power goes out, everyone knows, so reliability is paramount.”

Supply reliability in the natural gas market is being addressed not only by the huge increase in production capacity from shale plays, but also by ongoing expansions in gas storage and transmission across the country. Could large consumers start building dedicated local storage facilities to stockpile gas in lieu of long-term contracts?

“One critical outstanding question for reliability is how much on-site storage in caverns or above-ground tanks there is now or could be made available to some of the big gas-burning plants,” says Sweet, adding that gas sellers would be wise not dismiss the strategic and philosophical importance of a huge coal stockpile on site to executives and supply-chain managers who have to face angry customers as well as public utility commissions should the grid go down.”

When gas producers think about utility customers, it is important to remember that the sector is highly varied, says Skip Horvath, president of the Natural Gas Supply Association. If one subset is hesitant about long-term contracts, another segment may be more amenable.

He reports that in 2010-11, many suppliers took the initiative to hold discussions with their major customers. “Many were very interested, but our vocabulary of contracts, terms and conditions was somewhat disconnected,” Horvath recalls. “Our vocabulary has evolved since then. We are now talking about indexes rather than fixed prices. We are still working with many of those customers to try to craft agreements, but one group in particular was most eager: the municipal power sector. They understood the benefits of having some protection for both sides.”

Horvath adds that an important part of educating big gas consumers is helping them understand that there are many tools to manage risk, from supply contracts to financial hedges. “All of that liquid market for gas developed since the 1990s. It took a while for our own industry to adapt and adopt, and now the utility sector is going through the same learning process. Part of the problem is that the public utility commissions do not understand the risk management tools. In many cases, it sounds like speculating to them.”

With shale gas being found all over the country, Horvath says utilities are certainly buying capacity in commercial storage facilities. “The question is, can they get away from the comfort factor of a pile of coal on their property? The power companies own those piles of coal. They bought them and paid for them to be delivered. Over time, utilities will understand how reliable natural gas supply is, and that owning gas in storage or under contact for deliverability provides that same comfort factor, but with all the advantages natural gas provides.”

In the end, Horvath concludes, utilities will come around to a new way of thinking about the security of fuel supply as natural gas continues to demonstrate unsurpassed economic, environmental and reliability value across the country. “Utilities are building large numbers of gas-fired plants, so they are very clearly saying they have already accepted gas as the core fuel for the future,” he states. “All our members are very enthusiastic, but we understand it is a long education process.”

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.