New Capacity Bolstering Gas Demand

By Gregory DL Morris, Special Correspondent

When Technip announced in January it had been awarded a contract for a new ammonia plant in Louisiana, owned and operated by Mosaic Company, the drumbeat of new plants announced in the past year as a result of the shale gas boom grew louder.

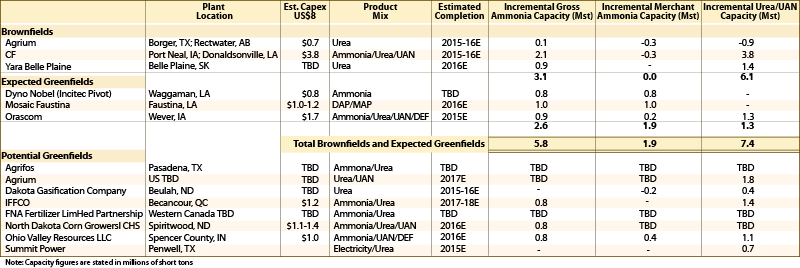

According to BMO Capital Markets, close to 6 million tons of gross ammonia production capacity is slated to be added in the United States over the next three years (Table 1). Another 5 million-6 million tons has been proposed, but BMO says it considers those projects speculative and lacking financial commitments.

An industry overview from The Fertilizer Institute (TFI) trade association states that the U.S. nitrogen fertilizer industry is both energy intensive and trade exposed, with 70-90 percent of the cost of production being attributable to natural gas, which is used as the principal feedstock and also as an energy source. “Farmers in the United States rely on domestically produced nitrogen fertilizer for a significant portion of their fertilizer supply, but must compete with farmers around the world for the remainder of this critical input,” TFI states.

That evaluation is corroborated by industry analysts. “The United States is structurally short of ammonia, which is the primary feedstock for producing nitrogen fertilizers such as urea and urea ammonium nitrate (UAN), and also serves as a raw input for phosphate fertilizers,” says Joel Jackson, lead fertilizer analyst with BMO Capital Nesbit Burns in Toronto. “The country imports 7 million-8 million tons of ammonia every year, as well as 5 million-6 million tons of urea and 2 million-3 million tons of UAN. The United States had not seen a new ammonia plant built in 30 years.”

Because ammonia historically has been a low-margin business, he notes that it has tended to be extremely sensitive to feedstock and energy prices. Fertilizer companies were among the first to seek offshore production when U.S. energy prices rose in the early 2000s, so the new and expanded plants are a seminal indication of the domestic manufacturing renaissance wrought by affordable and plentiful long-term natural gas supplies, Jackson affirms.

Crediting the domestic oil and gas sector for changing the economics of the fertilizer market, TFI states, “A reliable supply of U.S.-produced natural gas is boosting the domestic industry’s employment footprint by stimulating investment in nitrogen production facilities. This is in stark contrast to 1999-2007, when nearly half of U.S. nitrogen fertilizer production capacity and employment was lost to plant closures related to, among other things, high relative natural gas costs. The U.S. fertilizer industry is experiencing a renaissance, evidenced by announcements of restarting existing facilities and constructing new plants that could potentially double capacity and add billions of dollars to the U.S. economy. Each new facility brings jobs to construction workers and permanent, high-paying jobs to individuals who will work in those plants.”

Jackson explains that the United States is unique among major agricultural nations in that many farmers apply anhydrous ammonia directly in crop fields. The United States also applies a significant amount of urea and UAN, the predominant nitrogen fertilizers.

Strong Market, Solid Margins

The majority of urea and UAN imports come from Canada, says Jackson. “Specifically, they have come from Alberta and Saskatchewan production plants, where natural gas has been available at relatively low prices. China, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Eastern Europe also are suppliers,” he remarks. “Eastern Europe, most notably the Ukraine, using gas bought from Russia, is the highest-cost producer and the exporter that is likely to be displaced first as new capacity comes on stream.”

Anhydrous ammonia imports come primarily from Trinidad, which is also a huge world producer of methanol. “Two-thirds of U.S. ammonia imports come from Trinidad,” Jackson notes. “Canada and Russia supply most of the rest.”

Canada’s share of both anhydrous ammonia and derivatives exports to the United States will tick higher as the new plants come into service, but the calculus is a little complex, Jackson details. Some ammonia will be manufactured and used in the immediate area, and some will be used by the same company to produce derivatives.

Jackson says that while Mosaic made the original announcement that it was considering a new plant on the U.S. Gulf Coast, he adds that it was unusual for the company to let its contractor, Technip, confirm the details of the project by announcing its contract. According to Technip’s release, it was awarded “front-end engineering and design, as well as preparation of the corresponding engineering, procurement and construction proposal, for an ammonia plant under consideration by Mosaic. Mosaic’s preference is to locate the proposed plant adjacent to the company’s Faustina fertilizer manufacturing operations in St. James Parish, La. It would have a capacity of 2,200 metric tons a day.”

Technip also stated, “Mosaic is the world’s largest producer of finished phosphate products, with annual production capacity greater than the next two largest producers combined. The company’s plan is to backward-integrate more fully into ammonia production by expanding its capacity at Faustina. The proposed design of the plant will feature the Haldor Topsøe proprietary ammonia process technology that Technip has engineered and constructed in numerous projects. Technip also will perform the preliminary design work for the plant off-sites, utilities, interconnections, and other supporting units for the facility.”

The new nitrogen production will be taken up immediately by the market, BMO’s Jackson predicts. “The new plants will be able to sell right away, and they will displace tons back into the global market, which at the moment is oversupplied, so prices could be lower,” he foresees.

Given that ammonia production is so highly sensitive to raw materials and energy costs, The Fertilizer Institute has staked out a position opposing U.S. liquefied natural gas exports. A study of LNG exports conducted by NERA Economic Consulting for the U.S. Department of Energy came down squarely in support of exports, but TFI is among those encouraging exporting value-added materials such as pellets of plastic or urea, instead of LNG.

However, Jackson says natural gas prices would have to increase many fold before the new plants were seriously threatened. “Using published numbers by several major fertilizer makers, the industry would need a price of $200 a ton for ammonia if gas prices were at $5 an Mcf. Ammonia was selling at $600 free on board (FOB) Tampa (at the beginning of the year),” he observes. “At that price, gas could get to $11 an Mcf before these new plants were not profitable.”

Similar arithmetic prevails for ammonia derivatives, Jackson continues. “At a $5 gas price, you need to have urea cash costs at $170 a ton. (As of January) it was selling at $400-$450 a ton FOB New Orleans. The gross margins are something like 50 percent, even at the low end.”

Meaningful Increase

At the upstream end, the resurgence of ammonia production in North America is definitely a significant factor in unconventional resource economics. “We completed a multiclient study on shale gas, and we definitely see that segment increasing consumption of methane on a meaningful level,” reports Mark Wegenka, director of chemical consulting for IHS.

That said, Wegenka adds that fertilizer production is not a massive user of natural gas. “An ammonia plant consumes 30 MMBtu-35 MMBtu of gas for each metric ton of ammonia. The newest plants are on the lower end of that range,” he outlines. “Downstream from there, it takes 0.57 tons of ammonia to make a ton of urea, plus another 3.0 MMBtu-3.5 MMBtu of gas, so each ton of urea consumes 20 MMBtu-22 MMBtu of gas, including the gas that went into the ammonia feedstock.”

With that stoichiometry fixed, the amount of gas that the fertilizer sector can be expected to consume in the North American market will depend on how much new capacity is added. “The ammonia projects we feel are going to get done in the next five or six years come to about 6.5 million tons. Most of that capacity will be added within the near three years,” Wegenka says. “In urea, we feel for sure there will be an additional 7 million tons of capacity in production by 2020, with much of it being further processed into UAN.”

He reiterates that all urea production uses ammonia as a feedstock, and that some planned ammonia capacity is being constructed upstream of existing urea manufacturing, while some integrated ammonia/urea/UAN complexes are being planned. “In the end, that will back out some ammonia imports and most or all urea imports into the United States, except those from Canada,” he projects.

Taking that logic to the next step, the possibility could exist for the United States to export urea or other ammonia derivatives, at least regionally. “Urea is easily traded and shipped,” says Wegenka. “It is a nonhazardous, global commodity that can be moved at about half the shipping cost of ammonia. Urea is the vehicle for ammonia production in low gas-cost areas to be moved to high gas-cost agricultural areas. Nearly 25 percent of global urea production is shipped internationally.”

Wegenka stresses that he does not anticipate the United States or Canada becoming huge players in the global ammonia or urea markets–not with the huge producing regions in the Middle East between North America and the major agricultural markets of India and Asia–at least not in a pure merchant sense. However, he notes that some Asian agricultural interests are reaching out already.

“IFFCO (Indian Farmers Fertiliser Cooperative), the Indian fertilizer group, is involved in a joint venture in Quebec on the St. Lawrence Seaway,” Wegenka notes. “Its share of production is intended for export to India, but the project is still looking for financing. There is also talk of Fatima Fertilizer, the Pakistani company, building a plant in Indiana, but no formal announcement has been made. The Egyptian company OCI (Orascom Construction Industries) definitely is going ahead with its plant in Iowa, but that is for domestic markets.

“The global fertilizer market is very competitive, and there are other producers in low-cost areas that have existing customer bases,” he concludes. “I do not foresee the United States becoming a large global exporter, but perhaps a regional player.”

Securing Feedstocks

Rentech Nitrogen Partners is a publicly traded integrated ammonia and UAN producer based in East Dubuque, Il. It distributes the majority of its products under a long-term distribution agreement with Agrium Inc. It also sells urea-based diesel exhaust fluid (DEF) under contract to Yara International, the Norwegian company that is the largest global supplier of urea. DEF is a small, but specialized and profitable market, reports Rentech Nitrogen President John Diesch.

Early in January, as Technip was releasing details of its project for Mosaic, Rentech Nitrogen completed an upgrade and debottlenecking of its urea plant, adding 15 percent to its previous annual capacity of 168,000 tons. The next incremental expansion will be adding 70,000 tons a year of ammonia capacity to its existing 300,000 tons a year, Diesch announces. That project, which will include new storage capacity, is on schedule and due to be completed after the fall maintenance turn. The plant will be at its new production capacity by the end of the year, he says.

To secure raw materials, Diesch says Rentech Nitrogen deals directly with large natural gas suppliers. “We purchase at key trade point gateways, and pricing is done at a differential plus or minus to the New York Mercantile Exchange. In terms of the physical commodity, we receive the gas from our local distribution company, Nicor Gas, through the interstate carrier Northern Natural Gas Company,” he says, adding that Rentech Nitrogen pays the price at the interchange, plus transportation, which has been running $0.42 an Mcf.

Rentech has hedged both its raw materials and its finished materials, and is likely to do so again, but Diesch says the company is not running a big book on forward natural gas purchases. “When we get a prepaid contract for our products, we either have product inventory, gas strategically purchased in advance, or go buy the gas to put behind it. Sometimes we go a little long on gas, depending on the NYMEX curve,” Diesch details. “It is very tactical and has worked for us in these current market conditions.”

Strategically, Diesch says he is optimistic about the position his industry finds itself in. “The economics of fertilizer production in this country are very good, and that will continue, even if gas prices rise somewhat. We are expecting prices this year in the range of $3-$4 an Mcf. Over the next few years, we would not be surprised if gas prices rose to the $4-$5 an Mcf range, especially with an ultimate recovery of the U.S. economy.”

Diesch says he also is not overly concerned about overcapacity in the fertilizer building boom. “Historically, only about 30 percent of industrial projects that are planned or announced get built,” he points out. “It can be very difficult. New plants need siting and all kinds of environmental permits, while expansion projects often run into other types of constraints.”

That said, Diesch echoes industry analysts in saying he expects the proposed OCI plant in Iowa to be built. “OCI is a global player and is a construction company. Plus, it already has the permits in hand,” he remarks.

For fertilizer companies, expansion is a natural combination of strong demand, strong margins, and a secure feedstock position. “We are very bullish on demand for corn and all grains,” says Diesch. “The growth in corn is coming from food and feed, rather than ethanol. There is always a drought somewhere, so food and feed demand stays strong. Even when production is good worldwide, the increasing demand for protein in Asia means good demand.”

Diesch concludes by noting that Rentech Nitrogen is expanding its “natural hedges” by expanding its product lines in diesel exhaust fluid, and also in ammonium sulfate, which tends to go into different crops and other end-use markets from ammonia and urea. Rentech Nitrogen’s ammonium sulfate plant on the Houston Ship Channel in Pasadena, Tx., is the largest such facility in the country and consumes about half the amount of ammonia produced in East Dubuque, but purchases the ammonia from a different supplier and at a lower price than the ammonia sold from its East Dubuque plant.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.