Managing Associated Gas

Expanding Infrastructure, Improved Facility Designs Grow Multiphase Production

By Colter Cookson

With oil prices climbing to the mid-$60s, drilling and completion activity is accelerating. While U.S. rig counts are staying remarkably consistent with 80 percent of active rigs targeting oil, the production of oil in most of the nation’s horizontal resource plays comes with huge quantities of associated gas. This is one reason the U.S. Energy Information Administration predicts that dry gas production will set a record in 2018 at an average of 80.4 billion cubic feet a day, a 9 percent increase over 2017.

North Dakota’s portion of the Williston Basin offers a microcosm of the U.S. trend. According to the state’s Pipeline Authority, higher oil prices have increased the amount of acreage with economic drilling locations by 44 percent compared with 2017, putting the state on track to achieve record oil production in 2018. But there is a catch: Associated gas production is climbing with the increased oil output.

Enough natural gas accompanies the oil in the Bakken that the increased activity has led to tremendous growth in liquids-rich natural gas production. The same challenge that faces operators in other resource plays–figuring out how to best utilize the gas accompanying the oil in multiphase production streams–is compounded by the reality that local gas infrastructure and take-away capacity are insufficient to support that growth.

In response, says Ron Ness, president of the North Dakota Petroleum Council, the industry has doubled down on efforts both to use natural gas on site and to build the infrastructure needed to get it to market.

While flaring sometimes is necessary, Ness stresses that it is a last resort. “Natural gas is a critical economic resource,” he says. “From operators and mineral or royalty owners, to the state and the tribes, every stakeholder wants to see as many molecules of natural gas as possible captured rather than flared.”

Ness points out that the state’s Department of Mineral Resources requires operators to capture at least 85 percent of the gas they produce until November, when the mandatory capture percentage will increase to 88 percent. He says meeting that new goal will mean building gathering systems, processing plants and transmission pipelines.

“As an industry, we are forming a gas capture infrastructure task force, which will bring together producers and midstream companies to analyze aggregate gas production growth region by region and determine where more pipelines and processing plants will be needed,” he says. “The task force also will look at transmission lines for residual gas exports.”

According to Ness, the task force approach has a track record of success. “It is a tremendous tool for identifying challenges and bringing forth solutions,” he praises. “By aggregating production data, it provides a big-picture view of demand that allows midstream companies to invest in new infrastructure where it is needed.”

Midstream Investments

Lynn D. Helms, director of the North Dakota Department of Mineral Resources, reports that midstream companies already are stepping up to meet anticipated production increases. As an example, he cites a joint venture between Hess Midstream and Targa Resources Corp. to construct a natural gas processing plant capable of handling 200 million cubic feet a day. The Missouri Four Plant will be built at Targa’s Little Missouri facility, south of the Missouri River in McKenzie County, N.D.

Helms mentions that the facility is near the Fort Berthold Reservation, the area he says has had the most difficulty meeting the state’s gas capture goals. He attributes the area’s struggles largely to the lengthy process for getting pipeline rights of way on the reservation.

“Getting a right of way requires three separate approvals by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, three separate approvals by tribal officials and the consent of 51 percent of the Native American allottees on every tract it crosses,” he outlines. “It is an enormous, time-consuming process that could be streamlined without compromising its integrity.”

To promote such streamlining, Helms says the state Department of Mineral Resources is meeting with tribal officials.

The Missouri Four and three other gas plants scheduled to come on line in 2018 will boost regional processing capacity by 615 MMcf/d, says Justin J. Kringstad, director of the North Dakota Pipeline Authority, a nonregulatory agency that analyzes and forecasts production to help midstream companies make sound investments.

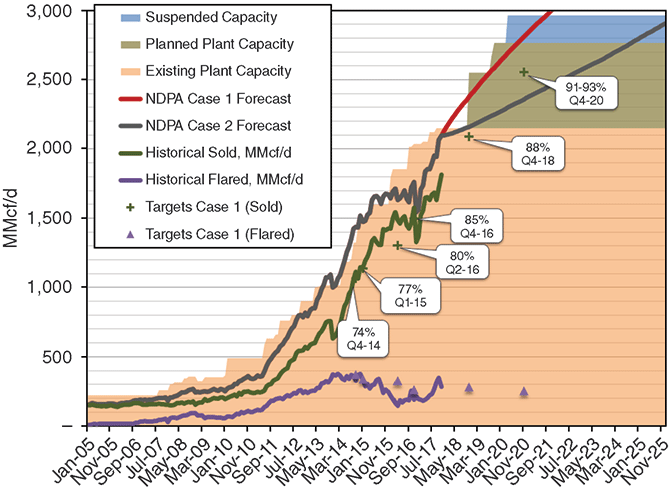

Until those plants begin coming on line later this year, Kringstad cautions that regional production will exceed processing capacity in the agency’s less conservative case (Case 1 in Figure 1), which he says January prices and activity levels support. “The industry is going to have to work hard to continue meeting gas capture goals, which likely will mean collaborating to move gas from systems that are at capacity to ones with spare capacity,” he warns.

By early 2020, Kringstad predicts, gas production again will exceed local processing capacity even with the four new plants. “There will need to be additional infrastructure investment that year and beyond for the industry to keep up with expected growth volumes,” he says.

Transmission Lines

In addition to new gas processing plants, Kringstad says the industry needs to invest in additional transmission lines. “One of the most immediate needs is more export pipelines for natural gas liquids,” he details. “NGL production already exceeds pipeline capacity, so companies are using regional trucks and long-haul trains to move NGLs to market. That works in the near term, but economics and expected long-term production growth support additional pipeline investment.”

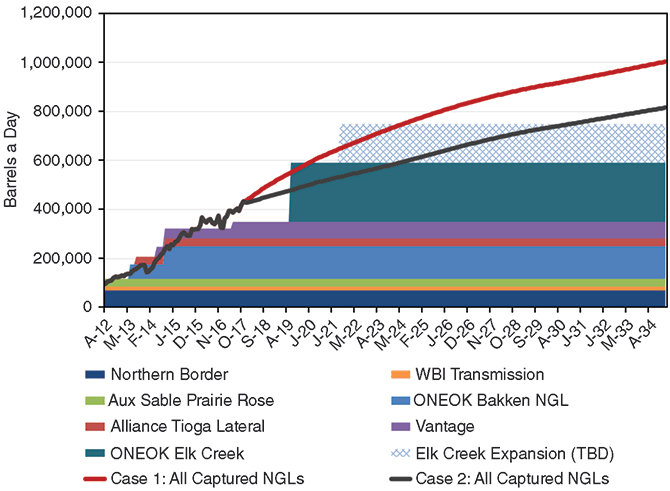

ONEOK announced in early January a project that should help alleviate NGL pipeline constraints. According to the company, the 900-mile Elk Creek system will take unfractionated NGLs from the Riverview terminal in eastern Montana to Bushton, Ks. The company says it expects the pipeline to enter service by the end of 2019.

Elk County will have a capacity of 240,000 barrels a day, Kringstad notes. He says that will be enough to meet industry demand until 2024, if production follows the agency’s more conservative production forecast. However, under its more optimistic projection, the pipeline would reach capacity in 2020 (Figure 2). ONEOK has the option to increase capacity to 400,000 bbl/d by adding additional pumps, an upgrade Kringstad predicts will be necessary under either forecast. In the more optimistic case, he estimates the expansion will meet demand only until 2024.

The industry will need additional dry gas transmission lines, Helms adds. “North Dakota has enough dry export transmission pipeline capacity to handle today’s demands, but within the next seven-10 years, our two export pipelines will be full,” he says. “In the best scenario, it takes three years to permit an interstate pipeline. With five-seven years being more common, now is the time to start talking to transmission companies about the next big project.”

The United States has abundant natural gas supplies, so Helms says future transmission lines may take North Dakota’s gas north to Canada, where it could be shipped to the coasts and converted to liquefied natural gas for export to Asian and European markets.

Alternative Uses

In areas without infrastructure, Helms says North Dakota’s operators are finding other ways to use natural gas and NGLs. “We have a robust industry of well-site NGL recovery units,” he illustrates. “These small, portable units are installed on multiwell pads, where they remove liquids to be trucked off site and sold. To the extent they can, operators use the remaining ethane and methane to fuel production equipment, heat hydraulic fracturing fluids and run electric generators.”

Some operators are experimenting with techniques that inject stranded gas to enhance oil recovery, Helms adds. “There are two natural gas injection pilots. One will inject the gas into vertical wells that are near horizontal wells, and then monitor the wells’ response. The other will apply a technique similar to one EOG Resources has been using in the Eagle Ford–a huff-and-puff process that involves injecting a set volume into a well, leaving it to soak for a period of time, and then producing it back.”

In the Eagle Ford, Helms says the huff-and-puff method has improved unconventional well production significantly. He references a 15-well field test that began in 2014. It increased each well’s production by 30-70 percent. “It will be at least a year before we know whether the process will work here,” he says. “However, we are excited. If it pans out, it should be applicable to most Bakken and Three Forks fields.

“In our efforts to relieve capacity constraints on export pipelines, we are leaving no stone unturned,” Helms concludes. He points out that the North Dakota Department of Commerce is talking with companies who may be able to use ethane to make plastics. In addition, one of the gas injection pilots is exploring whether injecting ethane improves recovery, a practice that could reduce the state’s export volumes by 20 percent.

Hydrocarbon Emissions

Even in areas with robust pipeline networks, operators must work to control hydrocarbon emissions, notes Mike Conder, a senior staff technical adviser at Bonanza Creek Energy. “In the Denver-Julesburg Basin, regulations are driving operators to eliminate as many volatile organic compounds as possible,” he says.

These regulations are part of a broader effort to meet the National Ambient Air Quality Standard for ozone, which forms when VOCs interact with nitrogen oxides in sunlight. Noting that the standard is difficult to meet, especially when much of the ozone blows in from other areas, Conder predicts the state gradually will ask the industry to meet even lower VOC limits.

“As Denver-Julesburg Basin operators have looked for ways to address VOC emissions, one of the biggest changes is a move away from putting oil tanks on individual wells,” Conder reports. “Instead, each well at each well site has a separator that breaks the production stream into oil, natural gas and water. These components are sent by pipeline to a central facility for storage.”

Those central facilities use a heater treater system to stabilize the oil as it comes in. Although stabilization reduces the amount of gas that flashes as the oil moves from high to low pressure, Conder says enough comes off that heater treater systems are equipped with intermediate-pressure vapor recovery units (VRUs).

The oil from the heater treater systems goes to a vapor recovery tower (VRT), which captures much of the flash gas. Finally, it is sent to storage tanks equipped with a vapor control system designed to capture any remaining gas vapors. Conder says these vapors can be sent to an emissions control device (ECD), which burns the gas in a way that minimizes emissions.

“Colorado requires that we design our storage tanks and vapor control systems in such a way as to eliminate leaks and minimize emissions outside of the ECD,” he says. “In other words, we have to design for the worst case of potential instantaneous flash gas production at the tanks.”

To handle those peak flash gas volumes, Conder says operators use robust ECDs and large pipe systems. To minimize the cost, he indicates that many operators are moving toward larger ECDs. “In the past, we might have put in a dozen 500-barrel tanks that were each hooked up to an ECD with a four-foot diameter,” he relates. “Today, operators are connecting multiple tanks to single ECDs with eight-, 12- and even 16-foot diameters, which reduces the footprint and could simplify maintenance.”

Conder adds that local operators are experimenting with improvements to their VRTs. “Paraffin forms as the oil cools in the towers, so periodically they may need to be taken off line for hot oiling. To slow the cooling and paraffin formation, operators are looking at insulating the towers.”

Operators also may be able to reduce paraffin formation by shortening residence times. In areas with multiple VRTs, Conder says operators may be able to achieve that goal by channeling all the oil into one unit. “The residence times are intended to break emulsions, but because the oil goes through a heater treater before it reaches the VRT, those rarely are a problem,” he comments.

In fact, Conder says it may be possible to eliminate VRTs altogether by running a heater treater at a low pressure, comparable to a VRT’s, such as two or three psi, and allowing the heater treater’s VRU to handle the gas that comes off. Then the now largely gas-free oil could be pumped into the tanks.

Tankless Designs

Because tanks offer several ways for emissions to escape to the atmosphere, Conder reports operators are looking for ways to bypass them by going directly from heater treaters to the sales line. In areas without pipeline infrastructure, he recommends installing lease automatic custody transfer (LACT) units.

“Almost all of our sites use LACTs for load-out,” he comments. “They improve safety by eliminating the need for someone to climb the tanks when there’s snow on the stairs, reduce emissions by eliminating the need to open thief hatches and cut the chance of a spill.”

Conder points out LACT units have economic benefits beyond improved safety. “Before LACT units, a hauler might spend 90 minutes on site, with half an hour spent hooking up and another 10-20 minutes spent testing the loads and occasionally grinding them to see if they contain water. The LACT unit handles all of that automatically, so the hauler can get in and out in less than an hour. As a result, he charges us less.”

Conder suggests using LACTs with Coriolis meters, explaining the devices offer greater accuracy. Because LACT units improve efficiency and safety, he says local trucking companies are fitting some of their trucks with LACT units to serve smaller pads that do not have their own.

Conder says Bonanza is benefiting from automation on tanks and other equipment. “With automated monitoring, our pumpers can focus on pads that need attention rather than checking every pad every day (though we do check them on a regular schedule). The reduced windshield time enables pumpers to concentrate on fixing problems and gives them time to cross-train and pick up new skills.”

Electric VRUs

Returning to vapor recovery, Conder reports that Bonanza is switching from gas-driven VRUs to units powered by electricity. “The electric VRUs reduce downtime from 10-15 percent down to 5 percent or less,” he says. “To get the downtime even lower, we may install backup units. Less downtime reduces VOC emissions, which means we can handle more oil at one of our centralized storage locations without passing emission thresholds that activate more complicated permitting regimes.”

Conder says the amount of oil each storage facility can process has gone up tremendously. “Four or five years ago, companies in the area pioneered central facilities that could handle 5,000-6,000 bbl/d, limited in part to VOC emission permits. Improvements that greatly reduce VOC emissions are supporting designs that can process much more, with fewer calculated emissions than earlier designs. This is a testament to the industry’s experience in operating these facilities and subsequent improvements in facility design.”

In addition to simplifying emissions control, Conder says sending production from multiple pads to a central facility makes gas lift more economic. “When I joined Bonanza Creek five years ago, I never would have imagined that we would have wells on gas lift for more than a year,” he recalls. “We have wells that have been on gas lift since before I came.

“The key is that we have changed from putting small, 200-horsepower compressors on each well to centralizing gas lift and using an 800 horsepower–or larger–compressor to serve several wells,” Conder says. “It is easier to maintain two or three high-horsepower compressors in one location than it is to keep 20 small, widely distributed compressors running, so our uptime has improved. The change has cut gas lift compression costs in half, allowing Bonanza to extend the gas lift window by injecting gas at higher pressures.”

Gas Lift’s Power

Gas lift can be one of the best ways to increase production from highly-deviated horizontal wells, says Cleon Dunham, the president, chief executive officer and secretary of the Artificial Lift Research and Development Council. “Horizontals often have gas slugs that are difficult for rod pumps to handle. In contrast, gas lift systems love gas and can handle it more easily,” he describes.

One of the advantages of gas lift in deviated wells is that it is straightforward to get valves into the curve with coiled tubing units or tractors, Dunham offers. “If it’s possible to place the valves where they need to be and if the well has access to a reliable source of dry gas, gas lift can be a great artificial lift method,” he assures.

The industry is experimenting with putting sucker rods into horizontal segments as well, Dunham notes. “The concerns there are tubing wear and rod drag,” he says. “To address those issues, operators are trying rolling rod guides that help the rods slide along the tubing without damaging it, as well as plastic tubing that is better at resisting rod wear.”

Above-the-curve ESPs can be used as well, Dunham points out, noting that companies are designing and proving new techniques for keeping gas out of the pump. However, he says gas lift often is the best choice for liquids-rich horizontal wells.

“When using gas lift, one of the primary goals is to optimize injection, ensuring that the ideal amount of gas is going into each well at all times,” he says. “In a field where compressors serve several wells, that means adjusting injection volumes if one of the compressors goes down. It often is more effective to reduce or stop injection into poor wells, to keep gas going to the best ones.”

An automated system that makes it easy to monitor pressure and injection rates is vital to that optimization, but installing it is not enough, Dunham stresses. “I have seen far too many companies invest in great equipment only to use it poorly and so have it provide little value,” he says. “An automation system is more than alarms. It’s a tool to monitor and optimize. But, for that to happen, employees need training that goes beyond the basics of using the system and highlights the ways it can improve production.”

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.