Methane Mitigation Goals Identify Best Strategies

By Erin Tullos

Over the last five years, the North American oil and gas industry has made a significant strategic shift toward embracing decarbonization. But to fully realize its potential as a source of affordable, cleaner volumes in the global fight against climate change, the industry must engage in a swift and coordinated effort to limit methane emissions.

Methane is 120 times as potent a greenhouse gas as carbon dioxide instantaneously (and 86 times as potent over a 20-year time horizon), but it only remains in the atmosphere a fraction of the time that CO2 does. That means, pound for pound, methane emissions have not only had an outsized impact on warming to date, but also that reducing methane emissions offers more immediate benefits. In fact, reductions today will be felt in as little as 10 years.

This increased awareness is precipitating key market changes across industry, its providers and investors, and in turn, elevating methane emissions questions to strategic ones that chief executive officers, chief financial officers and other executives must confront. The good news is that previously disparate regulatory streams and industry protocols are beginning to coalesce around industry-standard best practices that focus on increased measurement, which will drive more effective and affordable mitigation options.

Executives’ Concerns

With these industry standards only beginning to emerge, methane emissions are no longer exclusively the purview of localized operational teams, but rather, the basis of strategic questions keeping executives up at night.

While methane emissions have become relevant to a range of executives, the strategic focus varies between stakeholders and thus roles within an individual company. A CFO’s financial concerns differ from a regional executive’s evolving regulatory pressures, an investor relations director’s license-to-operate worries, or a marketing vice president’s questions about converting methane reductions into higher realized prices. But all these executives need good information to guide their decisions, as does a CEO looking across the range of methane emissions questions.

Even investors and policymakers grapple with decision fatigue as they encounter the numerous, and sometimes conflicting, options purporting to address methane emissions.

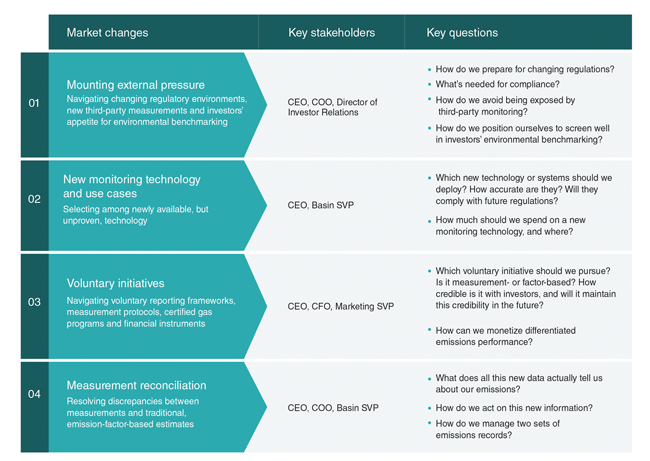

In our experience, operators typically progress through a series of strategic questions, detailed in Figure 1. Typically, their first concern is around mounting external pressure (01), both regulatory and nonregulatory, with first-party reporting requirements set to increase and third-party, outside-the-fence monitoring also ramping up.

As companies realize they will need to make public comments in response to this pressure, they typically purchase new monitoring technology (02), viewing this capital burden as modest relative to harder-to-abate emissions, such as the ones from combustion processes. However, methane emissions vary spatially and temporally, rendering this new source of data difficult to interpret with monitoring technology alone. We find that operators often end up frustrated with the return on their emissions monitoring investment and question what, if anything, they should do next.

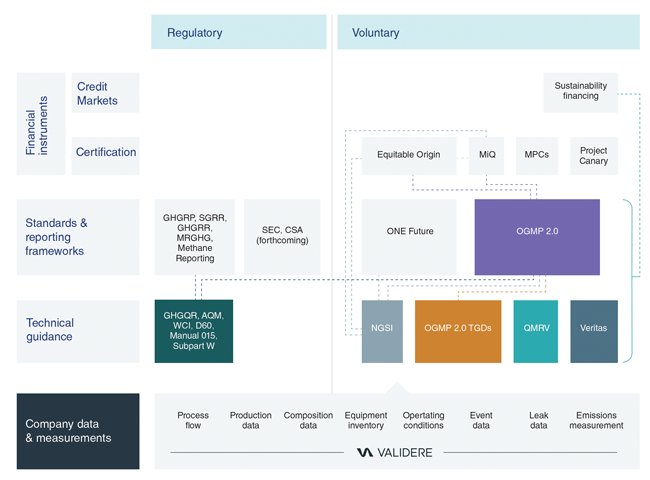

Next, their thinking often shifts to questions around voluntary initiatives (03), where they typically find an alphabet soup of programs (as seen in Figure 2). Operators are joining these programs in increasingly large numbers, with many participating in more than one as they struggle to decide between the programs or decode how these programs connect to their broader corporate goals, including their fiduciary obligation to increase shareholder value.

The ecosystem largely distills down to groups that attempt to solve for a few specific pain points. As they evaluate which initiatives to join, operators’ first step should be to clearly define their goals, such as reducing the cost of capital, managing investor pressure, improving realized prices or market access or quickly publicizing emissions reduction investments.

These overlapping certifications, programs and measurement protocols highlight the need for measurement reconciliation (04 in Figure 1), especially as operators must understand potential discrepancies between site-based measurements and the factor-based estimates often mandated by regulations. Operators fear future accusations of maintaining two sets of books with respect to emissions, particularly as emissions reporting becomes more embedded in financial disclosures and dictates audit standards.

External stakeholders are acutely attuned to the flaws associated with emissions estimates based on generic emissions factors. Instead, investors want to benchmark operators with measurement-based environmental performance. Investors see lower-emitting businesses as more sustainable, much as they see operators with longer inventory lives as more sustainable. Eventually, as improved measurement simplifies benchmarking, we expect better environmental performance to translate to higher EV/EBITDA multiples.

The Path Forward

As companies develop their methane management strategies, they find a range of challenges depending on their hydrocarbon mix, region and access to infrastructure, but also a range of cost-effective solutions.

What should operators do?

The first step is to identify emissions reduction goals. There is no one-size-fits-all solution to emissions monitoring and management, no tool so powerful and versatile it makes the other options irrelevant. In fact, the techniques for locating, quantifying and addressing methane emissions are evolving at a rapid pace. To select technologies that best suit their needs, operators must determine which problem or problems are most important to solve. For example, operators may want to:

- Reduce leak detection and repair costs, which will likely mean evaluating new technologies to verify that they are faster, cheaper or more precise than traditional cameras;

- Manage stakeholder critiques of emissions performance and benchmark well against peers;

- Find super emitters as quickly as possible;

- Move from emissions factor-based reporting to measurement-informed emissions reporting;

- Translate environmental performance into improved realized prices or market access;

- Cost-effectively achieve regulatory compliance and minimize tax obligations; or

- Increase operational efficiency

Establishing A Baseline

Once they have clarified their goals, operators’ next step likely will be creating baseline data so they understand where their emissions come from and can develop effective solutions. Data collection generally begins with:

- Identifying and listing emission sources;

- Performing a rapid survey to reveal any unexpected sources; and

- Revisiting the source list to prioritize the most material ones.

For long-term success, operators also need to:

- Evaluate existing—or straightforward to acquire—data sources for monitoring emissions;

- Select measurement technologies to perform discrete campaigns and/or ongoing surveys; and

- Perform site-level measurements to validate emissions inventories at least once a year.

Baseline characterizations can help all operators select the right technologies for their situations without overspending.

Before they invest heavily in new technologies, operators should figure out how much the operational data they already collect can help manage emissions. Environmentally relevant emissions are much smaller than engineering relevant quantities, so, for example, the difference in production meters at the wellhead versus at the inlet to a processing plant cannot be used to discern differences in parts-per-billion emissions. However, some signatures in operational data promptly can help identify areas of concern.

For example, a LiDAR flyover may detect abnormal tank emissions, which an operator can corroborate by looking at tank pressures in its SCADA system. But rather than relying on LiDAR to identify whether a tank was open and then retrospectively checking whether it has been resolved, an operator can flag potential abnormal tank emissions based on operational tank pressure data. Similarly, an operator should not need a flyover to determine whether a flare is lit; that too can come from SCADA data.

Selecting Technologies

Though it can be powerful, operational data is only one piece of an effective emissions measurement portfolio. A responsible operator must still select a range of technologies across its asset base, a particularly challenging task given the rapid changes to detection hardware, deployment methods and economics.

One challenge is that most operators do not understand the available measurement instruments’ strengths and limitations well enough to interpret the new emissions measurement data. Nor do most instrument vendors understand operations well enough to translate that data into actionable insights. Thus, as operators select measurement technologies, they must consider how to utilize and internalize the data so that it’s accessible and actionable.

Measuring and managing methane emissions is challenging, but the upside for operators, industry and the environment is massive, especially as the industry argues for long-term growth in North America’s natural gas production as a means of decarbonization. The specific technology portfolios operators deploy will vary depending on their mix of wells and facilities. However, all operators can benefit from improved measurement plans and systems. By augmenting these systems with existing operational data, they can shrink their emissions at a lower cost.

Editor's Note: Validere is exploring the questions and challenges this article discusses in a series on managing methane.

ERIN TULLOS is a senior adviser on carbon strategies at Validere. She has 16 years of experience in environmental research, regulatory advocacy and compliance. In addition to working as a senior adviser and uncertainty and reconciliation expert for the Oil & Gas Methane Partnership 2.0, part of the United Nations Environmental Program, Tullos is a visiting research fellow at the University of Texas at Austin, where she studies methane emissions and mitigation. She holds a Ph.D. in chemistry from Texas A&M University.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.