Natural Gas Outlook

Strengthening Prices, Improving Fundamentals In Store For Natural Gas Market

Although the past decade has been largely about tight oil, the first several chapters of the U.S. shale story were written at the turn of the century in dry gas plays such as the Barnett and Fayetteville, gradually expanding to the Marcellus/Utica, Haynesville and dry gas windows of others. With the global oil market situation, some domestic producers already are pivoting back to natural gas.

To get an expert perspective on the state of the U.S. gas market, AOGR met with Andy Weissman on April 27. Weissman is chief executive officer of EBW Analytics Group LLC in Washington, which provides energy market analytical services. Weissman has provided strategic advice to industry-leading energy firms for more than three decades and has played a key role in developing innovative structures for major energy transactions, and transforming state and federal energy and environmental policy. He is a graduate of Harvard Law School.

Q: The economic decimation related to COVID-19 is unlike anything the world has ever seen. For natural gas, the overriding concern is collapsing demand. In oil markets, demand destruction is only part of the story. In early March, Saudi Arabia and Russia launched an ill-timed price war that further undercut prices. When some sort of normalcy returns, what will the net effect have been on U.S. oil and gas markets?

WEISSMAN: I believe the events of today will dramatically reshape the gas market. The explosion in tight oil development during the past decade has resulted in huge increases in essentially “free” associated gas production. This has had major structural effects on the market, which tended to be oversupplied because so much incremental gas production was coming from tight oil plays. Even when gas prices declined, associated gas from oil plays continued to grow rapidly, exacerbating the supply glut. Going forward, we see chronic oversupply changing in a profound way.

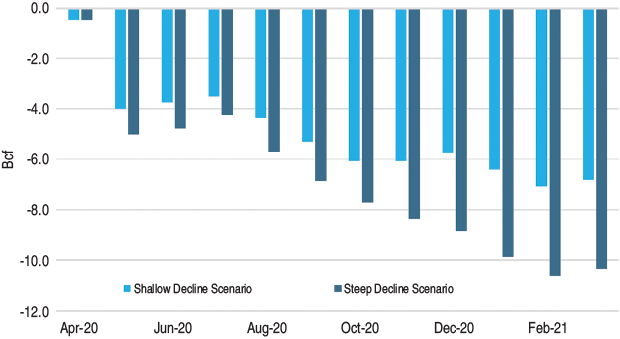

FIGURE 1

Projected Shallow and Steep Decline Scenarios

Of U.S. Associated Dry Natural Gas Production

(April 2020-March 2021)

Source: EBW Analytics

While oil prices will recover, it may take quite a while before total U.S. oil production gets back to where it was at the start of 2020. As a result, at least for the next few years, production of associated gas is likely going to be much lower. Oil-driven associated dry gas accounts for roughly 18 billion cubic feet a day of U.S. supply. We see a potential decline of as much as 9 Bcf/d by the end of this year, or half of the total supply (Figure 1). To put that into perspective, the potential decline is roughly equivalent to current U.S. liquified natural gas exports.

In this context, we should see natural gas prices strengthen considerably by next winter. As always, a lot will depend on weather, but assuming normal winter temperatures, we expect the natural gas market to tighten a great deal during the winter months and remain relatively tight into 2022. We also would expect that, in that circumstance, the question of the extent to which production can increase in Appalachia, the Haynesville, and to some degree, the gassier portions of the Eagle Ford, will become a fairly central issue. With higher prices anticipated, there will be substantial growth opportunities in those dry gas plays.

There are many implications of such a large loss of associated gas production, but the new normal going forward will be a return to the days when an increase in gas demand required a corresponding increase in dry gas production. Since associated gas is a byproduct of tight oil development, it grew rapidly even when gas prices were low. Looking forward, gas production will be much more responsive to price signals. This will help support higher prices and lead to dedicated gas drilling activity levels not seen in years.

Q: How quickly do you see associated gas output falling? How will that influence prices heading into the end of the year and the start of the winter heating season?

WEISSMAN: I suspect we are going to hit the wall very soon in terms of running out of storage capacity for oil and finished products. U.S. oil production may need to be cut by as much as 3.0 million-4.0 million barrels a day in a very short time. We already are seeing the biggest falloff in well completion activity in history. Unfortunately, cuts of that severity are necessary. Negative pricing does not leave one much of a choice. The rapid decline in oil production will lead to an abrupt and proportionally large decline in associated gas production. Our modeling indicates that associated gas supply will decline by 4.0 Bcf/d-5.0 Bcf/d in the three months from April 1 to June 30.

With this kind of sudden monumental supply shock, we expect lots of price volatility. The forward curve for natural gas can jump quite a bit when oil production drops abruptly. Later this year, we see additional production cuts coming that may stun both the oil and gas markets. For natural gas, the supply shock may come sooner and will lead to significantly stronger average prices in 2021-22 and perhaps beyond.

But before higher prices are realized next winter, this summer and early autumn are going to be very challenging for gas producers. The most likely scenario is that the market experiences two phases. First, with large demand losses from COVID-19, there is a substantial possibility that supply will be on a trajectory during this year’s injection season to exceed the total amount of usable storage capacity. As a consequence, prices could fall to new lows in early fall. It is possible that prices temporarily could dip to below $1 an Mcf before firming at the start of the heating season. How low prices go will depends largely on the strength of U.S. LNG exports and the speed with which declines in associated gas supply occur.

The good news is that with anything resembling normal temperatures, prices should increase sharply this winter. We think it is possible that 2020-21 will be the best winter for natural gas since 2014, when NYMEX Henry Hub prices climbed to nearly $5 an Mcf. There is definitely a good chance prices will get to the $3.00-$3.50 range. Is it possible that prices can climb well above $4? Yes, I think so, if the start of winter is reasonably cold, partly because associated gas production is likely to continue to decline during the winter with oil producers completing so few new wells. I see that price strength continuing past next spring into the rest of the year.

Q: To put market fundamentals aside for one moment, do you foresee any potential aftershocks from the COVID-19 response that could alter natural gas supply and demand fundamentals even long after America gets back to business?

WEISSMAN: There will no doubt be surprises and unforeseen dislocations. I tend to focus on the LNG market, but my concerns there mainly regard the risk of larger-than-expected export curtailments. Another wildcard could be the November election. It is possible that there will be a change of administration in the midst of all this disruption, with the new administration having a very different attitude toward natural gas development.

Looking two or three years out, we are going to need a lot more drilling and development in gas shale plays. If there is a change in administration, there are likely to be continued difficulties in adding new pipeline infrastructure, notwithstanding the need for more supply. That could lead to steeper price increases than the industry wants to see, including regional price shocks.

Of course, there would be an equivalent impact on the oil side, with downside or upside price risk depending on how one wants to look at it. One downside risk is the likelihood that a new administration would lift U.S. sanctions on Iran. Should that occur in a severely oversupplied market, it would not only be terrible news for oil producers, but suggest that it could take much longer for tight oil (and associated gas) production to rebound to pre-coronavirus levels.

Q: You have identified U.S. LNG exports as a determining factor in the near-term outlook for natural gas. LNG pricing was weak even before the first case of COVID-19 in China. What is your outlook for U.S. export volumes? Looking globally, to what degree does the historical collapse in oil prices make crude a more formidable head-to-head competitor to LNG?

WEISSMAN: LNG exports are absolutely critical to the future prospects of natural gas producers in the United States. But again, we need to make a sharp differentiation between the short term through mid-fall, and the longer term after mid-fall. As noted, between now and November, we see considerable downside risk. It is as clear as it could possibly be that there is a near-term glut of LNG supply. LNG exports will be reasonably healthy in May because of the timing and the notification requirements under various contracts, but at a minimum, I anticipate several Bcf/d of lost LNG demand and much more supply than the world market can absorb from June through at least September.

There are two layers of issues. One is the supply glut that already existed before the COVID-19 shutdown, which has been made worse by the huge loss of demand during the past two months. The second is the impact of low oil prices on the ability of U.S. LNG suppliers to compete with suppliers around the world, including those in Australia, for example, where LNG prices are oil-based.

I am also concerned about the potential for direct oil-on-gas competition. The world is going to be looking desperately during the next few months for ways to use all the excess oil. In late April, West Texas Intermediate futures prices for June were trading at a level that made oil less expensive than LNG on a delivered basis. If very low oil pricing continues, it could change global market dynamics and seriously eat into LNG demand. It is not sustainable and I hope it doesn’t happen, but there is potential for a demand crisis in late summer with steep declines in U.S. LNG exports.

With natural gas, however, there are strict physical limits on how much can be stored. This may lead to any near-term glut–domestic or abroad–getting cleared much faster than in the oil market. The key for global LNG demand remains gas used for space-heating purposes, so once we get to winter, the utilization factor for U.S. LNG liquefaction plants should rebound strongly.

Q: To summarize, you expect U.S. natural gas storage to be brimming and global LNG markets to be oversupplied for the next several months, but with a quick turnabout that sees very low summertime prices rallying to above $3/Mcf as storage is drawn down come early winter. What does that mean for producer hedging strategies?

WEISSMAN: I would again break it down into two phases. While there is a fair amount of hedging locked in for the rest of 2020, the downside risks during the next few months are extreme, and come at a time when the financial positions of many producers are precarious. As oil storage runs out and production is cut sharply, we may see a jump in natural gas prices. I would encourage producers to not miss this opportunity to hedge as much as possible of their remaining unhedged production through this fall. The downside price risk is substantial and the name of the game is going to be to conserve capital to make it to next winter.

Once we get to November and the start of the heating season, the downside risk will shift to upside potential. We have no way of knowing what weather for the upcoming winter holds, but the difference between a very mild and a very cold winter is on the order of 1.8 trillion cubic feet. Therefore, even though we predict higher prices in 2021, we recommend that producers still hedge a significant portion of their production through the first and second quarters since prices could still decline if winter weather is as mild as the winter of 2019-20.

Along with the usual weather risk factor, the other huge question is when the spread of the coronavirus will be under control to allow the economic recovery process to start. Will there be a “second wave?” Uncertainty is exceptionally high for winter 2020-21, since a second wave of COVID-19 infections is possible. But assuming the economy begins to reopen soon, triggering a rebound in demand, the supply/demand balance is likely to tighten significantly next winter. That means prices by the second quarter of 2021 could be the highest in five-plus years.

That said, my advice to producers is that it is essential to closely monitor the evolution of the coronavirus during the next few months. There is a real risk that the virus may break out again during next winter’s cold and flu season, and lead to an even more severe crisis requiring even more drastic measures than what we have seen this year. So even with the overall tightening of the market, COVID-19 may create renewed downside risk for natural gas futures next winter. Producers should be prepared to hedge farther out, say, through the first half of 2021, if it begins to look like the virus could return next winter.

Q: As the economy recovers, it is not hard to envision intense competition for investor dollars. Might capital availability become a barrier that puts a crimp on the natural gas market’s comeback?

WEISSMAN: That is an important part of the reason we think the market is going to become much tighter. I think it will take years for credit availability to return to anything close to the levels of a few months ago before the coronavirus shutdown. Even then, investors and lenders already were souring on oil and gas. The major banks that have heavy industry exposure are getting hit very hard. At the same time, there is a separate set of pressures from environmental watchdog groups trying to push banks to curtail lending to the oil and gas sector.

Put it all together, and both banks and private equity investors are likely to drastically cut back their exposures to the industry. I have advised some of the largest private equity funds, who already were increasingly hesitant to place capital in the oil and gas sector. But oil prices falling into negative territory was more than a wakeup call for them. Downside risks are demonstrably greater than previously assumed. Negative prices were something no one had even contemplated, and the fact that it happened only makes it more difficult for the industry to attract capital.

Producers are aware of that and want to be extremely cautious, which gets back to hedging. For some producers, it will be tough to find the capital to drill enough wells to provide the cashflow to work through their current indebtedness. Constrained capital availability also suggests that the gas market could remain relatively tight time for some time.

Q: The midstream sector has been an area of intense investment as onshore resource development has progressed. The pace has slowed, but several projects are still in various stages around the country. Do you see a continued build-out of pipelines and plants, particularly for moving gas south to export centers?

WEISSMAN: The long-term success of the domestic natural gas industry is tied closely to whether the United States can continue to expand LNG export capacity. There is still a tremendous opportunity to double or even triple our LNG exports during the course of the next 10 years, but it requires building a lot of new pipeline infrastructure.

Two issues are particularly critical. The first is what happens in regard to U.S. Supreme Court rulings on the Mountain Valley and Atlantic Coast pipelines expected to be issued in a few weeks. The second is the lack of adequate pipeline infrastructure to bring enough gas from Appalachia to Gulf Coast LNG terminals, especially if U.S. export capacity is to be expanded. Even when business conditions were a lot rosier, there was not enough new pipeline capacity being built to ship gas from Appalachia to the Gulf Coast. With the loss of associated gas supply from the Permian and elsewhere, this becomes a huge concern. Moreover, if there is a change in administration next November, the obstacles to building new capacity will be much greater.

Frankly, for the industry to prosper long-term, we need to do a much better job of explaining to the public the critical need for LNG exports to reduce carbon emissions in emerging market countries that rely heavily on coal use. We also need to make a stronger case regarding the need for new pipeline infrastructure to facilitate increased exports and protect customers in the Northeast against winter-month price spikes.

In this context, the Mountain Valley and Atlantic Coast projects are a crucial step toward building out the needed infrastructure. The Supreme Court is scheduled to issue a decision on Atlantic Coast by the end of June. The chances are good that the ruling will be good news for the industry and overturn a circuit court decision that blocked construction of both pipelines through national forests. If so, Mountain Valley could enter service this year, with Atlantic Coast following sometime afterward.

If the ruling is unfavorable and these two pipelines do not get built, the natural gas market could become extremely tight on a prolonged basis and it would dramatically limit opportunities to expand production and LNG exports. This litigation underscores the fact that there is a need for gas producers to present a comprehensive strategy to ensure that natural gas plays a central role in the United States’ energy future. We need to think boldly, because the world as we knew it before the coronavirus doesn’t exist anymore, and there will be a public policy debate regarding the future role of natural gas. The industry is facing a series of critical issues that require a comprehensive new agenda to define what the future of natural gas ought to be and determine how to get there.

Editor’s Note: The editors acknowledge Eli Rubin, research director at EBW Analytics Group, for his invaluable contributions to the discussion. Weissman and his team also have recently completed an in-depth report, “Impact of the coronavirus on the U.S. Natural Gas Market.” A free copy of the report's executive summary can be downloaded at https://ebwanalytics.com/pandemic-executive-summary.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.