With NGVs Taking Off, U.S. Transportation Sector Accelerating Natural Gas Demand

By Richard Kolodziej

WASHINGTON–One of the biggest questions producers have with respect to correcting the natural gas market imbalance is whether America’s transportation market is moving to natural gas fast enough.

With today’s price differential between abundant natural gas and diesel and gasoline greater than ever, the interest in natural gas vehicles by policymakers, fleet owners and even consumers is growing at a record pace. From over-the-road truck fleets to city buses and airport shuttles, the number of NGVs in the United States is growing every day. Natural gas also is beginning to move into the consumer market as the global automobile manufacturing industry rolls out NGV designs ranging from sleek European luxury sedans to classic Detroit muscle cars.

Yes, the U.S. transportation market clearly is moving to natural gas. But the more important questions are, “How quickly can the NGV market grow and how big can it get?” The answer to these questions depends on the price gap between natural gas and diesel/gasoline, vehicle availability, the fueling infrastructure, and to an extent, government policy.

Natural gas as a vehicle fuel has always had inherent benefits. It displaces foreign oil, which has been a stated priority for every U.S. president since the Arab oil embargo in the early 1970s. It produces fewer greenhouse gases than gasoline or diesel fuel, and it helps reduce urban pollution. Some people find these public policy benefits compelling enough to make the switch to NGVs. However, for the majority of fleet owners and most consumers, it is all about economics.

NGVs cost more to buy than comparable gasoline or diesel vehicles. Technology improvements, mass production, economies of scale and competition are bringing down that first-cost premium. However, there probably will always be some added first cost, if only because compressed and liquefied natural gas tanks are far more sophisticated (and costly) technologies than gasoline and diesel tanks. That said, this greater capital cost can be offset by lower–much lower in many cases–operating cost. In June, natural gas was selling at the pump for $1.50-$2.00 less per gallon equivalent than gasoline or diesel. So the more fuel a vehicle uses, the faster that first-cost premium can be recovered.

Attractive Payback

A rule of thumb is that fleets are willing to pay more, provided that they can recoup that investment in three years or less. So, for example, a natural gas trash truck that consumes 9,000 gallons of fuel a year would have an annual fuel savings of $13,500-$18,000. With a $30,000 incremental price, the payback is around two years. Small wonder that last year, almost 40 percent of all trash trucks purchased in the United States were NGVs, and in 2012, 50 percent are expected to be powered by natural gas engines.

But the vehicle does not have to be a big truck to see an attractive payback. A courier (such as a medical courier driving all over town to pick up medical test materials from doctors’ offices) driving a natural gas Honda Civic™ sedan easily could consume 1,500 gallons of fuel annually. If that Civic has a first-cost premium of $6,500, the payback is within the three-year target.

The operating savings are impressive today. But the big question being asked by many fleets thinking about switching to NGVs is what about tomorrow? Will natural gas keep its price advantage into the future? After all, crude oil prices fell below $80 a barrel in June. Obviously, the future oil price is unknowable. However, the consensus is that once the world economy starts to improve, oil prices will climb again. Meanwhile, many argue that natural gas in the $2.00 a Mcf range is unsustainable. They may very well be correct, but industry experts appear to agree that the U.S. supply of natural gas at a cost of $4.00-$6.00 an Mcf would more than meet demand.

So consider this. Natural gas makes up a much smaller percentage of the delivered price of the fuel at the pump than either gasoline or diesel. The majority of the delivered price of compressed natural gas and liquefied natural gas at the pump is not the natural gas. It is made up of transportation and distribution cost, compression or liquefaction cost, fueling station operating and maintenance, excise taxes, etc. All those costs may add to $1.50 a gasoline gallon equivalent (GGE).

Natural gas in the field at $2.00 an Mcf equates to only $0.25 per GGE (there are eight gallons equivalent in each Mcf of natural gas) for a pump price of $1.75. If the field price was to reach $4.00 an Mcf, the natural gas component would still only be $0.50/GGE for a pump price of $2.00. At $6.00 an Mcf, the pump price would be only $2.25. Natural gas for vehicles is expected to continue to be very economically attractive, compared with gasoline and diesel under all reasonable future scenarios, positioning NGV technology to take off in all segments of the transportation market.

Growing Selection Of NGVs

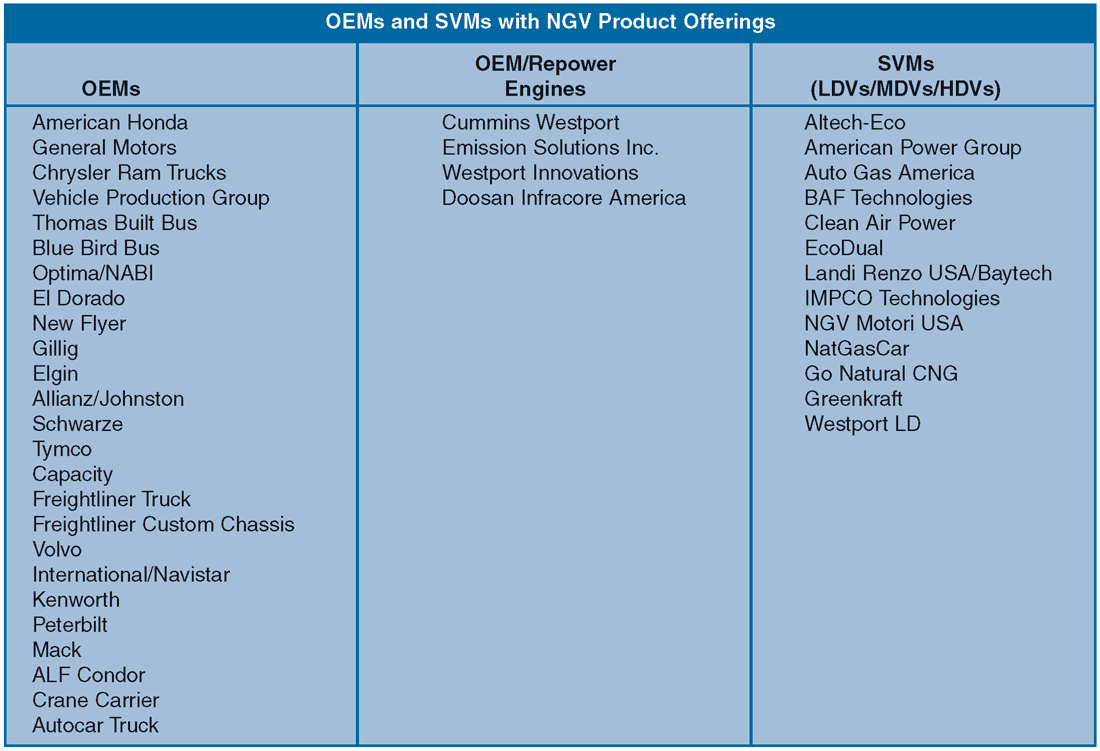

Historically, one of the criticisms of NGVs (as with all alternative fuel vehicles) was that vehicle options were limited. That is no longer true, especially in the heavy- and medium-duty markets. Table 1 shows the growing selection of NGVs from original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) as well as small-volume manufacturers (SVMs).

Every trash truck, transit bus and street sweeper manufacturer now offers natural gas models. Two of the three largest school bus manufacturers offer natural gas models. In the large truck market, Freightliner, Kenworth, Mack, Navistar, Peterbilt and Volvo all offer natural gas trucks.

A wide range of natural gas shuttle buses, step vans, vocational trucks, work trucks and specialty trucks also are available. General Motors is offering a medium-duty dedicated natural gas van and will be rolling out a bifuel pickup truck by the end of the year. Chrysler is offering a medium-duty bifuel pickup. Ford offers five engines with the gaseous fuel prep option, facilitating conversion companies’ retrofits of new or relatively new commercial vehicles. And the list goes on.

In the light-duty market, while every major vehicle manufacturer offers natural gas models in Europe, Asia or South America, only Honda sells a natural gas model in the United States today: the dedicated Civic natural gas sedan. But there are a growing number of SVMs that produce natural gas aftermarket conversion systems that have received emission certifications from either the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency or the California Air Resources Board. Systems have been approved for gasoline vehicles made by GM, Ford, Dodge, Volkswagon, Mitsubishi, Mazda, Workhorse, Isuzu, JAC and Freightliner Custom Chassis.

Converting diesel vehicles is one area in which NGV offerings have been lacking until recently. While new OEM heavy-duty NGVs have been entering the market in record numbers, there are 8 million diesel vehicles on America’s roads. EPA’s onerous emission certification process had made it too costly to certify diesel conversions. But in March 2011, EPA issued new regulations that somewhat streamlined the certification process, especially for “outside of useful life” vehicles.

The definition of “outside of useful life” varies by vehicle type and size. For example, for light-duty gasoline engine vehicles (weighing less than 8,500 pounds), it is 120,000 miles/10 years or optional 150,000 miles/15 years. For 2004 and later heavy-duty diesel engine vehicles (weighing more than 33,000 pounds), it is 435,000 miles/22,000 hours/10 years, whichever is less.

As a result, a number of companies have received approvals from EPA for aftermarket diesel conversion systems, and many more are on the way (most of which are dual-fuel systems). Dual-fuel vehicles have two fuel tanks–one for natural gas and the other for diesel. The vehicle starts, and for the most part, idles on diesel. However, as the vehicle accelerates, an increasing amount of natural gas is used, so that up to 60 percent of the fuel burned is natural gas over the entire duty cycle. If natural gas is not available, the vehicle has the ability to run on 100 percent diesel.

At an alternative fuel conference, there was a panel discussion on diesel conversions. The consensus of the panelists (all manufacturers of diesel conversion systems) was that, because of the very attractive economics, there could be up to 300,000 such conversions on the road within five years.

Fueling Infrastructure

The biggest barrier to more rapid growth in NGV usage is fueling infrastructure. There are about 150,000 gasoline stations around the country. While 42 percent of these stations offer diesel fuel, only a tiny percentage (about 1,100) have natural gas stations. The infrastructure is growing by 15-20 stations a month, and that rate is increasing. However, because of the limited fueling station availability, NGVs cannot be all things to all people–at least not yet. In the meantime, much of the industry has been focusing on customers that do not need a national fueling network.

First are “return-to-home” vehicles. There are millions of vehicles in every city and town that park overnight at a lot or depot, leave in the morning to work all day, and then return to the same lot. These include, for example, trucks that deliver packages, beer, soda, bread, snack foods and linen. It also includes buses of all kinds (transit, school, shuttle, etc.). For large fleets, one fueling station located at a home depot can serve the entire fleet. For smaller fleets, one station located in an industrial park can serve dozens of smaller fleets.

A second category of customer that does not need a national fueling network is “point-to-point” vehicles. There are tens of thousands of trucks (mostly large 18 wheelers) that do nothing but drive back and forth, delivering goods between two cities, such as New York to Boston, Los Angeles to San Francisco and Houston to Dallas. These are really return-to-home vehicles with two homes. A fueling station at each home can serve those vehicles. A large portion of the NGVs put on the road over the past several years were return-to-home and point-to-point vehicles.

Recently, there have been announcements quickening the pace of expansion of the national natural gas fueling infrastructure. In January, Clean Energy Fuels Corp. announced that it would build 150 new LNG fueling stations as part of what it called “America’s Natural Gas Highway.” These stations will primarily serve the huge over-the-road truck market. The company anticipates having 70 stations in 33 states–some of which also will offer CNG–open by the end of 2012, with the remainder opening in 2013. Many of these stations will be co-located at Pilot-Flying J Travel Centers. Pilot-Flying J is the nation’s largest truck stop operator with more than 550 retail properties in 47 states.

On June 7, Shell Oil Co. and TravelCenters of America LLC (TA) announced that they planned to build and operate LNG fueling lanes for heavy-duty trucks at about 100 of TravelCenters’ 238 nationwide fueling locations. Again, the target customer is over-the-road trucks.

Meanwhile, for smaller commercial fleets and consumers, a number of chains are entering the market. For example, Kwik Trip, a 400-unit upper-Midwest convenience store chain, is adding natural gas fueling capability at five high-traffic locations, with more stations planned as local commercial fleets and consumers adopt NGVs. Likewise, On Cue Express and Love’s Travel Stops are rolling out stations, and additional regional chains are evaluating similar options.

Other companies also have plans to build stations to serve smaller fleets and individual consumers. In urban areas such as Los Angeles and Salt Lake City, there are already enough public natural gas fueling stations to go beyond large fleets, and return-to-home and point-to-point vehicles. As more of these NGV station “hubs” develop and as more stations are located along the highway corridors (refueling “spokes” connecting the hubs), a truly national natural gas fueling system will evolve.

Government Initiatives

In general, NGVs historically have been ignored by government policymakers while they embraced more exotic, but often unproven, alternatives. But legislators and regulators at both the federal and state levels have gotten impatient with the unfulfilled promises of these other technologies. Now that policymakers are becoming aware of America’s vast natural gas resource base, NGVs finally are getting the positive attention they deserve.

At the federal level, there have been many bills introduced in Congress that would encourage the growth of the NGV market. The most important is the NAT GAS Act. Introduced in the House of Representatives as HR 1380 in April 2011 and in the Senate in November 2011 as S 1863, the NAT GAS Act would provide a number of financial incentives to fleets and consumers to increase the population of NGVs on the road. NGV advocates are working with their congressional champions to possibly have the provisions of this bill enacted into law by the end of this year.

The administration also is actively supporting NGVs. On Jan. 26, standing before several large natural gas trucks at a UPS facility in Las Vegas, President Obama unveiled his Blueprint to Make the Most of America’s Energy Resources. As part of that four-point blueprint, the president called for a series of programs that would reduce the nation’s dependence on oil by “encouraging greater use of natural gas in transportation.” Also as part of that effort, on Feb. 23, the president announced a $30 million research and development program to “promote transformational breakthroughs in the development of CNG storage cylinders.”

While these federal-level developments are very encouraging, much more action is happening at the state and local levels. Because of California’s special environmental problems and concerns, that state has long been in the vanguard in providing incentives for and otherwise promoting NGVs. In part, that is why there are more NGVs of all types in California than in any other state. But the rest of the country is catching up fast.

Utah has been a strong NGV promoter for a number of years. More recently, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Texas and West Virginia have enacted or expanded incentives for NGVs. In Pennsylvania, Governor Tom Corbett has issued an executive order that would accelerate the number of NGVs on Pennsylvania’s roads along with the number of natural gas fueling stations. And, in the Pennsylvania Legislature, a series for NGV bills have been introduced that, if passed, could make Pennsylvania among the leading NGV states. Since the beginning of 2012, more than 250 pieces of legislation have been introduced in the 50 state legislatures that would promote incentives for alternative fuel vehicles, and NGVs would qualify for almost all of them.

Of special note is the memorandum of understanding signed by 13 states (Colorado, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Mississippi, New Mexico, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Texas, Utah, West Virginia and Wyoming). The purpose of the agreement, which was initiated in November 2011 with four states, is to encourage automobile manufacturers to begin producing an array of original equipment manufacturer-built fleet NGVs that also will meet the needs of the general public. To accelerate this process, the states propose to issue a joint NGV purchasing solicitation that aggregates annual state fleet vehicle procurements.

In April, the 13 state governors sent a letter to 19 automakers urging them to increase the production of NGVs, accompanied by a series of questions about automakers’ plans for producing NGVs and how aggregated purchase volumes might affect the cost of NGVs. This initiative could have a major impact on the number of light-duty original equipment manufacturer NGV models being offered in the near future.

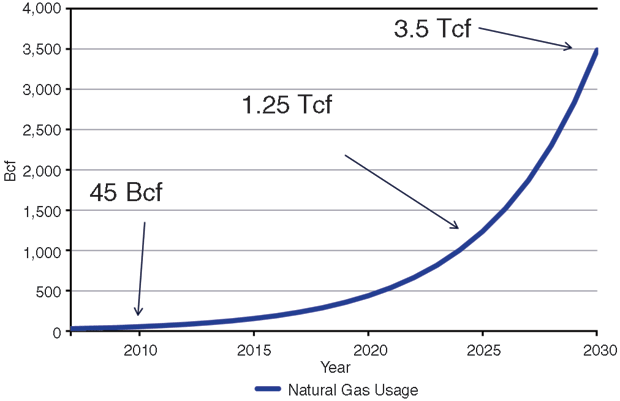

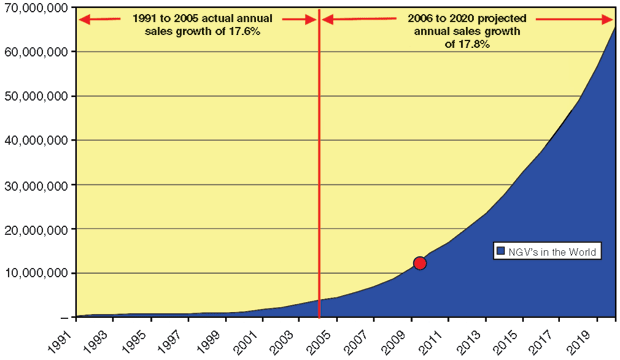

Forecast Gas Consumption

In 2010 (the latest year for which data are available), it is estimated that NGVs consumed 45 billion cubic feet of natural gas in the United States. By 2025, the market is projected to grow to 1.250 trillion cubic feet (Figure 1). Is that really possible? Absolutely. Consider what is happening around the world (Figure 2). In 2005, the International Association of Natural Gas Vehicles forecasted worldwide NGV growth to 2020. That forecast had the same type of aggressive growth curve that the U.S. market is now anticipating. Despite a global recession, the number of NGVs worldwide today sits right on the line of that growth curve. Without that recession, the NGV count clearly would be ahead of the forecast.

Today, everything is aligned for America’s NGV industry. NGVs always have offered public policy benefits. Now the nation has the natural gas supply, the vehicles and the economics, and it is well on its way to having the fueling structure. And, because of all the public policy benefits, NGVs now have public policy support. That support is not essential for NGV growth; the market will grow in any event. But with favorable public policy at the federal, state and local levels, the NGV market could grow much faster, and the many public policy benefits provided by NGVs would be realized that much more quickly.

The transportation fuel market is only a little smaller than the entire market for natural gas in all applications, including residential, commercial, industrial and power generation. So if natural gas captured all of the on-road market, annual U.S. demand for natural gas would almost double. Such a situation is not really possible, or even desirable. However, considering that diesel fuel use in America’s trucks and buses is the equivalent of 5.250 Tcf a year, it is very possible to capture at least 20 percent of this market. And, coupled with capturing a small percent of the 17.0 Tcf-equivalent gasoline market, that 1.250 Tcf target by 2025 is quite achievable.

So, the answer to the key questions of how fast the NGV market can grow and how big it can get is “fast and big!”

RICHARD R. KOLODZIEJ is president of NGVAmerica, a national organization dedicated to developing a growing, sustainable and profitable market for vehicles powered by natural gas and biomethane. NGVAmerica represents more than 130 engine, vehicle and equipment manufacturers, as well as fleet operators and service providers, natural gas companies, environmental groups, and government organizations interested in promoting natural gas as a transportation fuel. Prior to joining NGVAmerica in 1996, Kolodziej was group vice president of the American Gas Association, where he held a variety of senior positions. He is past chairman of the International Association of Natural Gas Vehicles, president of the American Biogas Alliance, and a member of the Transportation Research Board’s Alternative Fuels Committee. He also serves on the board of governors of the National Energy Foundation. Kolodziej holds a bachelor’s in economics from Rutgers University and a master’s in urban and regional planning from the University of California at Los Angeles.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.