CO2 EOR Poised To Unlock Reserves In Vast Residual Oil Zones

By Steve Melzer

For decades, the industry ignored oil shows below the producing oil/water contacts. Prevailing theories attributed these shows to a transition zone, in which the ratio of oil to water started high and decreased until no oil shows were present. Under this model, the shows simply reflected the ratio’s gradual change. If a well reached the transition zone, it would primarily produce water.

Today, many geoscientists recognize this model as too simplistic. In numerous fields, the so-called transition zones are highly saturated with immobile oil and should be described instead as residual oil zones (ROZs), which can be capable of producing additional reserves.

This occurs partly because oil/water contacts are not fixed in place on a geologic time scale. In fact, many reservoirs have rich tectonic histories that have exposed the paleo oil/water contact to natural geologic forces and adjusted the lower boundaries of buoyant fluid entrapments.

By understanding when and how these geologic forces cause oil/water contacts to shift, operators can locate ROZs, and in due course, significantly expand the reserves they have access to.

Three Types

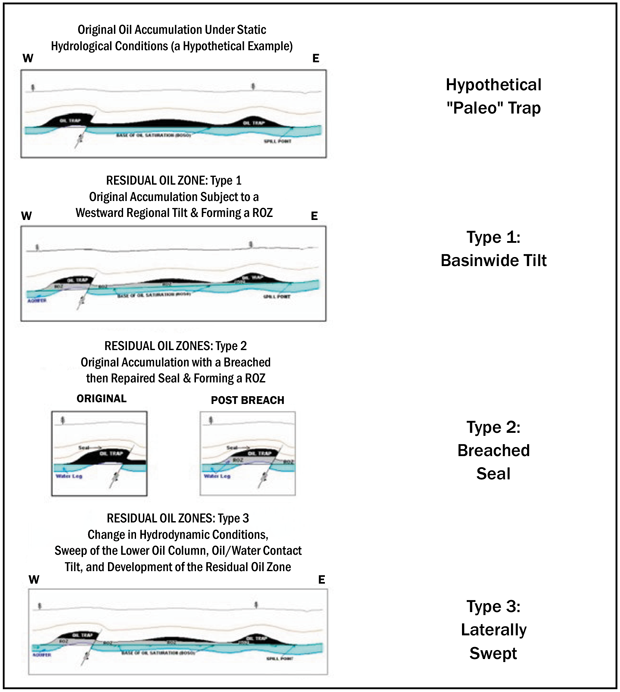

The industry’s quest to understand ROZs began with a technical paper presented two decades ago at the Society of Petroleum Engineers’ Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, and it continued with a more detailed study funded by the Research Partnership to Secure Energy for America. This early research classified ROZs into three types based on the tectonic forces that created them:

- Type 1: Post-entrapment tilt of an entire basin;

- Type 2: A breached seal, which has often been re-healed; and

- Type 3: A lateral influx of water, also known as a natural side sweep of the entrapped fluids.

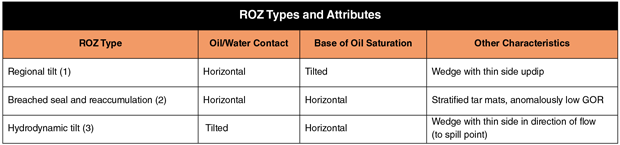

Figure 1 illustrates these mechanisms by comparing an ROZ of each type to a hypothetical oil accumulation that entrapped oil (the paleo trap). Table 1 discusses each type’s characteristics.

The growing and now conscious awareness of how dynamic entrapment boundaries can be has led to many ROZ discoveries around the world. However, the classic case remains the San Andres formation in the Permian Basin, which has ROZs that are 200-300 feet thick. These ROZs originate from post-entrapment uplift of the western side of the Permian and an influx of meteoric water moving through the formation from west to east, meaning they fall under the third classification.

Unlocking Value

Today, many industry pioneers recognize not only the presence of ROZs but also their economic value when exposed to enhanced oil recovery techniques. Since 2008, more than 20 projects have extended CO2 floods into ROZs.

In all cases, these floods originally targeted fields that had been successfully produced using primary and secondary recovery techniques. However, two of the projects produced oil from areas where the original paleo oil entrapment had been entirely swept by what is now called Mother Nature’s Waterflood.

Much to the surprise of most observers, the studies reveal that residual oil saturations frequently exceed 25% and remain relatively constant down to the top of the paleo oil/water contact. The saturation levels resemble those found in the swept zones of a waterflood. The high level of immobile oil is likely a function of oil wettability and reflects the influence of indigenous microbes.

Broad Opportunity Set

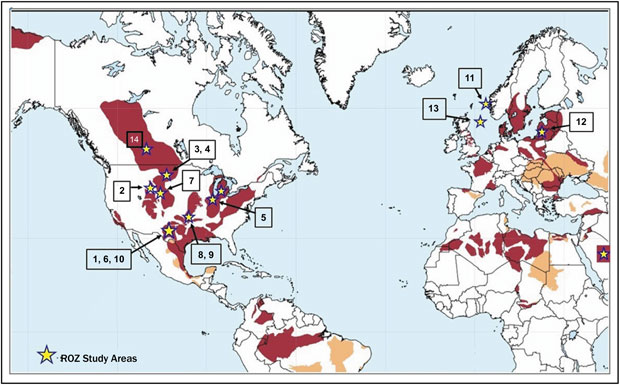

The Midland CO2 Conference has shown that ROZs represent a global opportunity. Because the event has a long history of dedication to ROZ science, it draws attendees from around the world who want to maximize their region’s ROZ potential by networking with their peers. These include experts from the United Kingdom, Lithuania, Australia, Denmark and Brazil, many of whom gave presentations about their experience with EOR projects that tapped ROZs.

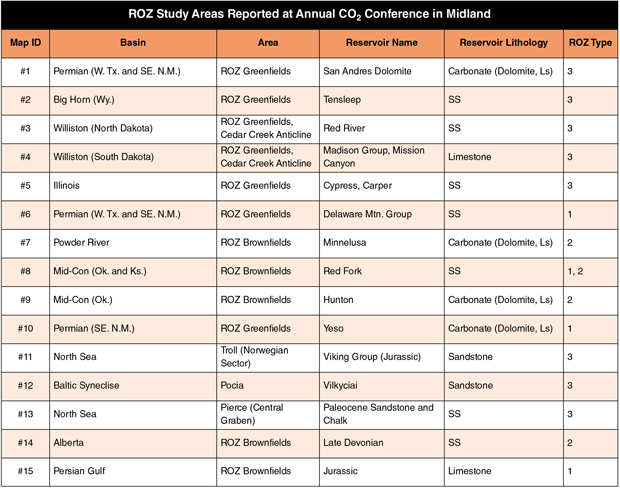

Figure 2 shows a map of the ROZ study areas that have been referenced in reports or papers. It also includes information from conversations at the conference and other communication. Table 2 provides more detail on the study areas, including the ROZ types, location, geologic age, and formation.

Although ROZs’ oil saturations generally fall below 40%, interest in developing them is growing due to the potential of CO2 EOR and the added value of incidental CO2 storage associated with the floods. This interest will only grow as industrial facilities take advantage of tax incentives for capturing CO2 and as regulatory reform mitigates some of the hurdles to building CO2 pipelines.

For the most part, commercial ROZ exploitation has focused on ROZ sections below the main pay intervals in existing fields. These can be called brownfields since the wells are already drilled and the cost to deepen them into the ROZ can be quite low.

While they lack such cost savings, greenfield ROZ projects can also be attractive, especially for laterally swept Type 3 ROZs. These ROZs tend to have huge aerial extents and can have thick intervals, so they contain immense amounts of oil to extract and the potential to store significant amounts of CO2.

One particularly interesting example not yet reflected in the figure or table lies in the panhandles of Texas and Oklahoma, extending into southwest Kansas. Its closest analog is the North Sea ROZ the map and table identify as #11, where deep fluid flow moves upward to long distance discharge points, all the while tilting oil/water contacts and creating Type 3 ROZs along the way.

The map and table also point out several Type 2 ROZs in Lithuania. These ROZs owe their origin to a second post-oil-entrapment stage of faulting in the Baltic region.

Similar Type 2 ROZ opportunities are noted in Australia. There, the high oil field occurrence in the Cooper and Eromanga basins seems to be due to the imperfect nature of reservoir seals, which is often caused by long-term or even short-lived natural gas leakage through imperfect seals resulting in upward migration of the deeper oil/water contact.

International Analogs

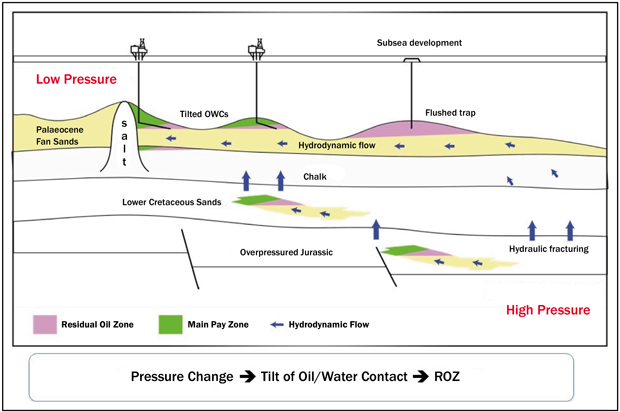

In 2016, Jamie Stewart and Stuart Haszeldine of the University of Edinburgh in Scotland brought the aforementioned North Sea case history to the conference that is marked as the eleventh study in Figure 2. The case study presented an example of a tilted oil/water contact (and ROZ) in the Pierce field that explained two expensive dry holes.

The oil/water contact’s tilt likely resulted from hydrodynamic flow from deeper overpressured Jurassic fluids moving into the Paleocene sand oil reservoir (depicted in Figure 3). This case history has a striking resemblance to the work done on the Permian Panhandle/Hugoton by Raymond Sorenson documenting tilted oil and gas/water contacts, underpressured reservoirs, and fluid flow, possibly to Mississippian outcrops in eastern Kansas.

This mention of ROZ studies would feel incomplete if it did not provide more details on the classic case mentioned earlier: the San Andres formation in the Permian Basin. The San Andres is particularly notable because of the enormous oil in place calculations performed by Advance Resources International.

Advance performed a careful study on 11 counties on the Central Basin Platform region of the Permian Basin, characterizing both higher and lower quality oil resources in the greenfield areas of the San Andres formation. This research documented 190 billion barrels of oil-in-place, of which 135 billion were of high quality, offering promise of commercially viable EOR development.

The ROZ resources are all of the Type 3 variety due to the western uplift of the paleo Permian Basin exposing the San Andres as outcrops. The influx of meteoric water finds its way downdip and to the east, forming a natural waterflood and tilting the oil water contacts due to the hydrodynamic gradient. Much of the paleo entrapment of San Andres oil was in the swept “fairways” (greenfields), but there are brownfield ROZs below the modern trap closures.

Such tilted oil/water contacts in large U.S. fields were observed as far back as the 1950s. The seminal geologist M. King Hubbert documented them in his classic study and laboratory modeling reports. However, it took much longer for research to explore the science behind the hydrodynamics that the field studies reported, the effects of altered wettability, and why oil shows occurred in areas that lacked an overlying field worth producing using primary or waterflood recovery techniques.

Even today, identifying, evaluating and producing ROZs remains an embryonic field, with much to come to light in the future. As time passes, researchers will continue to discover recurrent geologic dynamics that influence where fluid entrapment occurs and define oil field geometries.

The huge ROZs already found show how valuable that research can be. As the world’s need for energy expands, it’ll likely become vital to tap the reserves contained below the oil/water contacts in regions where the industry already has expertise, manpower and equipment. These ROZs contain vast quantities of oil that can be extracted with new twists on proven enhanced oil recovery techniques.

STEVE MELZER is the owner of Melzer Consulting, through which he has spent three decades helping companies understand the mostly private and complex marketplace for carbon dioxide. In the process, he has assisted large independent oil and gas producers, majors and midstream firms, the University of Texas, the U.S. Department of Energy, and nongovernmental nonprofits. Melzer also serves as the co-founder and managing director of the annual CO2 Conference in Midland, a nonprofit event that gathers experts in CO2-based enhanced oil recovery and carbon capture, utilization and storage while raising funds to support scholarship programs for the Society of Petroleum Engineers and the University of Texas Permian Basin. Born in Winfield, Ks., Melzer earned a bachelor’s in geological engineering from Texas A&M University, as well as a master’s in rock mechanics from Purdue University.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.