Safety Managers Leverage New Data To Mitigate Biggest Risks

By Colter Cookson

When companies care about safety, it shows. Workers can tell the difference between leaders who view safety as one of many compliance checkboxes and ones who care deeply about ensuring that everyone makes it home. That commitment shows up in daily decisions, quick action on observed risks, and safety programs that evolve as industry conditions change and technology improves.

While even the most safety-conscious companies have limited resources to invest, their efforts have a huge impact on workers’ lives and the company’s overall risk profile. That impact will only grow as more detailed data and more efficient analytical tools help safety teams identify and prioritize their biggest risks.

Well control is one of many areas that demonstrate how effective sustained risk mitigation efforts can be, says Joe Dean Thompson, senior vice president of global operations for Wild Well Control. “Since 2010, there has been a steady decline each year in the number of blowouts that cause a fire,” he says. “Today, the number of fires a year is in the single digits.”

When the industry enters new areas or begins experimenting with new techniques, incidents tend to rise, Thompson notes. For example, more problems occurred as the industry began to drill horizontals. However, such increases tend to be temporary.

“As an industry, we are good at solving problems,” Thompson says. “We may not get it right the first time every time, but we figure it out.”

Shale Completions

The industry’s current focus on tight shales reinforces other factors that have made blowouts less common. “If we ever go back to drilling deep gas wells, we could see a slight uptick in fires, even though we have better training, technology, and safety awareness,” Thompson says. “But in shale wells, Boyle’s Law is less of a problem. Gas doesn’t move into the wellbore as it might in sandstones and other more permeable formations, which makes it easier to maintain well control.”

When issues do occur, they often relate to completion or workover operations rather than drilling, Thomson says. “If there is any uptick in events today, it is in the completion space,” he says. “As laterals have gotten longer and more complicated, the wellbore tends to be exposed to the stimulated formation for a longer period as the completion is buttoned up. During that work, the hydrostatic pressure imposed by the completion/workover fluid should keep gas from entering the wellbore. But if it doesn’t, a kick will occur.”

Thompson says that in 2023, the Energy Workforce & Technology Council established SecureWell, a certification program that focuses on maintaining well control during cased hole operations rather than drilling, and concentrates on well control issues that are more commonly seen in workover operations in mature fields. Earlier this year, Wild Well Control became one of only a few companies that provide the training necessary to receive SecureWell certification.

“We are pretty excited about being part of this program,” Thompson says. “Through it, we can provide basic well control training to employees at service rig companies that work in cased hole and historically have not received this type of training. It’s too early for us to see what effect the training will have, but it should mitigate some potential problems.”

Advice On Call

When companies are dealing with pressure concerns or suspect they may be facing a kick, Thompson encourages them to call experts early. “We’ve told people for decades that it does not cost anything to talk to us,” he says. “There have been many cases where we spend a few minutes or a few hours over several days helping a company work through an issue and resolve it themselves.”

In more severe situations, Thompson says operators will often ask Wild Well to put an expert on site to help them troubleshoot a problem. “Typically, this pressure control work happens when a client has a potential or actual barrier failure of some sort, whether it be a valve or other component of the well envelope. Somewhere, there is concern that a loss of integrity has occurred, and maybe it’s complicated with mechanical issues from lost tools in the hole, stuck pipe, casing failure or other factors.”

Longer laterals and more complex well designs come with many benefits, but they also increase the potential for well control incidents during drilling, completion and workover operations, Wild Well Control observes. The company says the industry is taking steps to minimize that risk, including refining existing well control certification programs and launching new ones that focus on applying key principles to cased hole operations.

The on-site guidance can be helpful enough that some insurance programs offer incentives to encourage their clients to take advantage of it. “The insurance companies have quantitative data over the last 15 years showing that when we’re called out early, they have fewer claims to pay, and those claims are less severe,” Thompson says.

According to Thompson, the risk reduction comes partly from a fresh perspective. “Imagine a drilling superintendent or a consultant who has been looking at a well for weeks,” he says. “Maybe they’ve been dealing with lost circulation. Maybe there is a leak path somewhere that they are trying to locate and resolve. Over time, they can develop biases or simply get worn down.

“When they ask us to offer a fresh set of eyes, sometimes we look like geniuses,” he quips. “We’re not any smarter than our clients, but we get to look at this stuff every day. When someone on our team isn’t on a job, they still see the daily reports coming back from the people who are.”

Thompson mentions that Wild Well has master service agreements with more than 600 companies across the globe. “We have gotten to work everywhere you can imagine, from the tops of mountains to the deep blue sea,” he says. “Describe a well, and there is a good chance we have done work on several that are similar, especially over a decade or two.”

Fire Response

Thompson says it’s usually possible to keep pressure issues from escalating into blowouts. The blowouts that do happen typically involve situations where several smaller issues stack up.

When Thompson entered the well control industry in 1982, blowout response teams would sometimes put out fires by using explosives to push the oxygen away. “Today, we have figured out how to extinguish fires with larger water pumps,” he says. “We have set our nozzles up to spray water to the point where we can extinguish virtually every fire that has existed up to this point.”

Finding people with the right attitude to excel at preventing or responding to blowouts can be a challenge, Thompson allows. “We need somebody who is willing to take a call in the middle of the night, bounce out of bed to answer questions about a well they have no previous knowledge of, grab their coveralls and hard hat, and jump in the truck to drive to a well pad or an airport. They’ll only return home when the problem is solved, and they need their family to be happy with that.

“It seems absolutely ludicrous, but many of us at Wild Well have done it for decades and would not trade it for anything else.”

Younger workers who prefer troubleshooting pressure issues and fighting oil well fires to a day at the office have remarkably similar personalities to their older peers, Thompson says. “They also get excited when they have a chance to look at and solve a particular type of problem.”

Addressing Serious Risks

In oil and gas and beyond, companies are increasingly focusing their safety resources on preventing significant or severe events, says Tom Knode, principal consultant at the vPSI Group.

“Historically, many companies would evaluate safety performance based on total recordable incident rates and lost time rates,” he recalls. “The problem with that is that many of the incidents TRIR captures are minor events where somebody gets a small cut or sprains their ankle. That can impact people’s lives, but not on the same level as events where heavy equipment gets dropped or a blowout occurs. Those can lead to fatalities or lasting impairments.”

When deciding where to put safety resources, Knode emphasizes that it’s important to consider the potential outcomes of events rather than merely their actual outcomes. He says learning from close calls that could have been catastrophes will usually improve safety more than concentrating on events that only cause minor injuries.

As companies develop strategies to prevent Significant Incidents or Fatalities (SIFs) or near-misses from reoccurring, Knode encourages them to ask whether their solution truly addresses the issue’s root cause. “We see a lot of companies put a lot of energy and effort into understanding the incident itself, only to take corrective actions that do not reduce the chance of the event happening in the future,” he says.

“For example, one of the most common responses to an incident is to issue a safety alert and talk to their crews about the incident,” Knode says. “Safety alerts are good for acknowledging an event occurred, but they do not change the reality of how work is done. If the conditions of the work are what led to the incident, letting people know it happened will not meaningfully reduce risk.”

Training can also be ineffective if the incident does not stem from a lack of knowledge but from other factors, Knode warns. “When a near-miss or incident occurs because someone didn’t follow a process, companies often default to re-teaching that process,” Knode says. “However, there are a variety of reasons people ignore processes. If someone only has a few minutes to complete a task, they are unlikely to follow a cumbersome process that takes 50 pages to describe.”

In some cases, Knode says simplifying an unnecessarily complex process can improve compliance. In others, the best course may be technological. “Let’s say a driller accidentally runs the traveling block into the crown block,” he says. “We have seen corrective actions ranging from ‘we told the driller not to do that again’ to installing systems that sense when a block is approaching something else and automatically stops it.”

Evaluating Solutions

When deciding whether corrective action will be effective, companies should consider whether it targets the root cause of the event and whether the people tasked with implementing it have the authority to make the necessary changes. “The goal is to change the way work is being done so that an employee hired five years from now will not encounter the same circumstances,” Knode says.

One challenge to effective corrective action is that identifying root causes can be time consuming. “There are many root cause analysis tools out there, but if a company tries to apply the most intense ones to every incident, it’s unlikely they’ll have the resources to dive into why particularly concerning events occurred,” he says. “In those situations, people tend to default to generally acceptable but not necessarily effective corrective actions, such as safety alerts and retraining.”

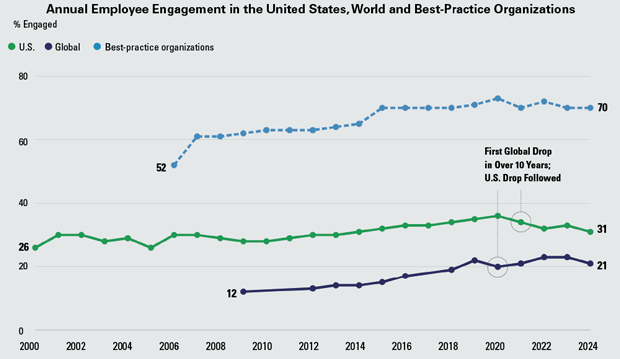

Gallup’s global employee engagement surveys suggest that well-managed companies can achieve much higher engagement than their peers. That’s good news, because studies link engagement to higher performance on a variety of metrics. For example, a large, multi-industry meta analysis that Gallup published in 2020 found that companies in the top quartile of engagement had 64% fewer safety incidents and 23% higher profits than companies in the bottom quartile.

Because of resource constraints, Knode recommends reserving detailed root cause analysis for complex cases that warrant thorough review. “When company standards mandate that the same root cause tool be applied whenever there is a recordable injury, employees often end up doing work that is unnecessary on simpler events, such as trips and falls,” he explains.

For serious events that do justify root cause analysis, Knode urges companies to go beyond eyewitness testimony when other data is available. “People’s brains aren’t perfect recording devices,” he says. “They don’t see or remember everything, but they feel like they do because our brains can fill in the gaps with something that sounds logical but never happened.”

Regardless of the data available, Knode advises companies to approach investigations with humility. “We all have cognitive biases,” he says. “Our brain uses a lot of energy, so we rely on shortcuts to make sense of the world.”

According to Knode, those shortcuts can get investigators into trouble. As an example, he says seasoned employees’ experience with similar events can lead them to assume the same root cause is behind the one they’re currently examining. They might also have trouble remembering that others lack their knowledge and miss the potential for mistakes they would never make.

Conversely, Knode continues, a less experienced investigator may lack the knowledge to identify the root cause or put too much weight on the opinions of a more senior peer. To help prevent such mistakes, Knode says vPSI has created cheat sheets for investigations that list the biases most likely to take them down the wrong path.

Leaders’ Role

Using limited resources prudently and conducting root cause investigations carefully can improve companies’ safety, but Knode says the most important element is leadership. When employees feel safe enough to tell upper management about issues or incidents, they are more likely to follow processes, point out problems and take warnings seriously.

“Companies should have discussions about the realities of work with the front line,” he advises. “Ask them to identify the most dangerous things they do and how the company can help reduce the risk of an event or injury, then act on that information.”

When employees see changes that address their concerns, they tend to become more engaged with their work, Knode says. “Lots and lots of research shows that companies outperform their peers when they have a more engaged workforce,” he says. “That edge extends from safety to financial performance and service quality.”

Leveraging Workers’ Observations

Safety teams have long recognized the importance of frontline workers’ observations and concerns, says Garrison Haning, CEO of Safety Radar. In fact, many companies have spent decades encouraging workers to report near-misses, good catches, incidents, and observations. To facilitate that, the safety industry has developed tools to make filing reports as fast and convenient as possible for workers.

Today, some of the data previously reported manually can be gathered automatically. For example, AI-powered cameras can track when employees enter danger zones or use improper form while lifting objects.

“We have gotten so good at pulling information from the field that it is exceeding our capacity to look at it,” Haning says. “There are only so many safety people. Even with operations teams checking reports as well, companies can’t keep up with the data.”

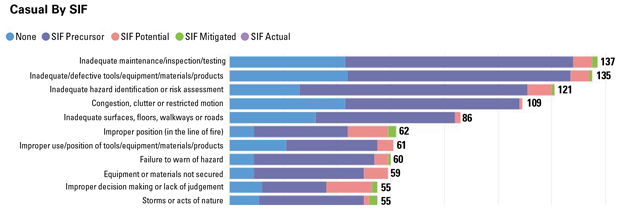

New AI tools allow safety teams to analyze observations, hazard assessments and other documents from frontline workers more quickly and thoroughly. According to Safety Radar, such analyses can help safety teams track risk trends and decide where to invest time and other resources. For example, this demo graph categorizes concerns by cause and how close they came to triggering a serious injury or fatality. ("SIF Mitigated" refers to an event where a SIF could have occurred but did not because safety barriers or controls worked as designed.)

Some of Safety Radar’s client companies used to analyze only 10% of the safety-related reports their employees submitted, Haning illustrates. “There are important signals in those reports, but for a long time, the best way to separate the signals from the noise has been manual analysis,” he says. “Now, we can use AI to look at every report and identify the biggest safety concerns for the company.

“Every report is assessed to the customer’s standard, with incident causes, actual severities, potential severities, potential SIF exposure (pSIF) and process safety assessment aspects all being extracted,” Haning enthuses. “Every breadcrumb we can glean out of these reports is being used to their fullest extent.”

In addition to looking at safety reports, safety-focused AI can evaluate the hazard assessments that employees conduct as part of their work. Because it has been trained on large, industry-relevant datasets, Haning says the AI can detect increased risk of serious injuries and fatalities. “When the AI has that context and access to job hazard assessments, it can start to tell people who are about to do work, ‘I know you didn’t specifically call this out, but this particular step in this process is actually really dangerous. Be careful.’”

For safety managers, the AI can point out priorities. “It can look at all the locations across the company’s footprint and recommend the places where the safety director, safety manager or regional superintendent should be to have the most impact, as well as some of the risks they should look out for there,” Haning says.

Haning says safety AI can also take a much broader view. For example, it can look at six months of data to produce a report that reveals trends.

“I cannot tell you the number of times we have had potential customers say, ‘Go ahead and run this analysis, but it won’t tell me anything I don’t already know.’ Then they get the report, and as they’re reading through it, they’ll say, ‘I knew about this, and I knew about this.’ But every time, that’s eventually followed by, ‘What’s this? Oh. We’re going to need to focus on that.’ It’s awesome, because that’s when we know we’re making a difference.”

Enabling Adaptation

Because safety AI can analyze reports quickly, Haning says it frequently allows safety teams to address potential concerns before they lead to an incident. “One of our companies had some near misses while pressuring up equipment that made it clear the field crews did not appreciate how dangerous the pressures in their equipment were,” he relates. “The AI picked up on that and flagged it. Within a week and a half, the company was training its crews to be more aware of pressures and use the controls to protect themselves.”

When workers notice their observations are influencing training and equipment investments, Haning says they tend to be more willing to submit reports. “For some companies, we have seen a 400% increase in safety engagement, meaning observations being submitted,” he shares.

For safety managers, the time savings alone can make investing in AI worthwhile. “The exact time savings depend on the company’s size and how thoroughly it analyzes reports, but for some companies, it is multiple people’s worth of time every year,” Haning says. “Instead of spending days combing through their inbox and analyzing reports, the team can go out into the field and help the people they are trying to take care of.”

Aside from handling routine report analysis, Haning says the AI can generate reports that used to require a week or more of work in only 15 minutes. This capability empowers safety managers to ask questions that would have once been impractical to answer.

The AI’s analyses can differ from the ones produced by hand, but they are accurate enough to be useful, Haning assures. Early on in a deployment, the AI will read a safety report similarly to a member of the safety team about 75% of the time. As the AI receives feedback from that team, Haning says accuracy typically reaches 90%-95%.

At first, most companies check every report the AI generates. As they get comfortable with it, they’ll drop to 10% for a month or two, then go to a much smaller number, Haning says. He adds that Safety Radar’s data science team checks the output as well. “Like anything else, quality control will always be an important part of what we do,” he says. “We will never get to a point where we say, ‘The AI knows what it is doing, so we no longer need to check it.’”

Even so, the AI has proven useful enough that Safety Radar’s clients include Coterra Energy and Williams, as well as S&R Vapor Recovery, which manufactures and services vapor recovery units in basins across the United States. The company analyzes data for organizations with 60 employees as well as huge firms with massive safety databases and operations across several continents, Haning adds.

“We are at an inflection point,” he argues. “We hear plenty of discussions about the AI bubble, and I’m sure there will be applications that will have the wind let out of their sails at some point. But using AI to keep people safe is not one of them. It is such an awesome opportunity to get better outcomes.”

Protecting Lone Workers

As companies look for ways to prevent injuries, particularly serious ones, their appetite for data on the risks that front- line workers face has grown, observes Yves Carrier, business development director at Blackline Safety. He says that trend is helping companies shift their approach to protecting lone workers.

Traditionally, companies would rely on a check-in system where workers would call a colleague when they arrived at a location. If that call never came, the company would assume something unexpected had happened and send someone out to investigate. “This is a low-frequency but high-consequence situation,” Carrier notes. “If someone is working alone and an event occurs, the risk of a fatality or serious impairment increases the longer it takes for others to realize something’s wrong and respond.”

By using cellular or satellite connections to send alerts and enable two-way communication, connected wearables allow companies to respond quickly and effectively when lone workers need help, Blackline Safety says. The company points out that its wearables include gas detectors, which warn employees of dangerous concentrations while recording lower concentrations that sometimes reveal unseen risks.

Recognizing that reality, he says many companies have adopted connected lone worker protection systems that track employees’ locations and send alerts as soon as something seems amiss or an employee requests aid.

“With our cellular-based systems, when a worker pulls the device’s panic latch, an alarm hits the dashboard within a few seconds,” Carrier says. “Beyond that, the response will depend on company preference. In some cases, an alarm will trigger text messages and emails to several managers. In others, a Blackline Safety agent will call the worker using their phone or the two-way communication on the device to figure out the nature of the emergency, then call a manager or 911 based on the response.

“Data transfer over satellites is a little slower than over cellular,” Carrier notes. “However, within 30 seconds to a minute of an event happening, our satellite-enabled systems will route the same data to different stakeholders and let them know an employee needs help.”

Gas Detection

Today, Carrier says connected safety devices increasingly integrate gas detection and other capabilities that allow them to provide context when an event occurs. To explain why that matters, Carrier imagines a pumper stepping into a pump shack after a leaky valve caused H2S to fill the space.

Ideally, the pumper would react to the gas detector’s warnings in time to leave the area. “But if there is a man-down situation, because of the gas detection capability, the responders will know they need to be prepared for high H2S levels and suit up before they go to rescue that employee,” he says.

In other situations, spending time putting on safety gear could be unnecessary. For example, Carrier says it’s common for alerts to be triggered by health issues, such as heat stress, strokes or heart attacks.

“Real-time alerts are only one component of how gas detection can help organizations improve safety,” Carrier says. “By saving the sensor’s readings, including low readings that don’t warrant an alert, we can give safety or industrial hygiene managers historical data on specific employees’ exposure to gases.”

Sometimes that data can help safety managers spot and mitigate risks before they lead to an accident. “For example, a manager at one of our clients in the Permian Basin noticed that one employee had much higher explosive gas concentration and H2S readings than others in the same position,” Carrier relates. “When the manager called to ask about the periods of high exposure, he discovered the employee was performing maintenance incorrectly and needed to be retrained.”

Such insights are unusual, but Carrier says they’re common enough to bolster the already strong case for integrating gas detectors with safety devices. “Most companies already spend money on dedicated gas detectors that need to be replaced periodically,” he says. “We can frequently lower their total cost of ownership for that need while adding other capabilities.”

Those capabilities are affordable enough to be available to a variety of firms, Carrier assures. “We have every single type of client imaginable,” he says. “In addition to large global organizations, such as Shell, ExxonMobil and ADNOC, we work with small oil and gas service organizations that employ a few people, as well as sole proprietors who want to reassure their families that they will be safe.”

As safety-focused companies’ appetite for data grows, so will the need for efficient ways to integrate data from disparate devices, Carrier suggests.

“In the next five years, we will likely start seeing partnerships between equipment providers designed to make it easier for their data to get to a manager’s dashboard,” he envisions. “Even the largest companies can’t partner with every vendor to figure out how their technology stack works and the best way to receive data from it. But if vendors align how data flows, we will be able to add features and capabilities to devices to give companies information they can use to improve both safety and productivity.”

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.