Devon Drives Progress Of Horizontal Well Refracturing In Vintage Eagle Ford Wells

By Al Pickett, Special Correspondent

The Eagle Ford roared onto the U.S. shale development scene in 2008 as a new hot spot, as production started with dry gas in the deeper part of the play and then quickly moved updip to the wet gas and oil windows. In the 15 years since, thousands of wells have been drilled and completed into the Lower and Upper Eagle Ford intervals in a play area that spans some 400 miles and 22 South Texas counties.

According to the Texas Bureau of Economic Geology, the typical Eagle Ford well has an ultimate recovery ranging from 200,000 to 400,000 barrels of oil equivalent in primary completion. But many of the producing wells in the play were completed with what now can be regarded as “vintage” stimulations. The industry’s collective understanding of how to optimize hydraulic fracturing designs to maximize formation productivity has evolved considerably since the Eagle Ford’s early days.

If operators could hit the rewind button to go back in time and redesign the completions in those early wells, what would they change and how would that have affected production and estimated ultimate recoveries over time?

Those are intriguing questions considering the huge strides made over the past decade in completion designs specific to tight oil plays, limited remaining access to undrilled core acreage in the Eagle Ford fairway and the sheer volume of reserves locked away in the thick, ultralow-permeability rock.

And it begs the million-dollar question: Do the economics add up to make refracturing existing wellbores worthwhile? If so, how can refracturing be used as a feasible strategic complement, or perhaps even alternative in some cases, to new well drilling campaigns?

Devon Energy has invested significant effort and resources in recent years to coming up with definitive answers, and in so doing, is recording increasingly remarkable success with Eagle Ford refracs.

In the third quarter of 2023, Devon Energy’s production averaged 665,000 barrels of oil equivalent a day, which translates to a year-over-year production increase of 8%. This production comes from a diverse portfolio that includes assets in the Delaware, Eagle Ford, Anadarko, Williston and Powder River basins.

Devon entered the Eagle Ford in 2014 through an acquisition. Initially, its focus was mainly on primary development across an inventory with expansive running room. Over time, as its primary development program proceeded and drilling locations were reduced, Devon began shifting its development focus to secondary and tertiary recovery.

“Reserve recovery through recompletions has become pivotal,” acknowledges Brian Schmitt, Devon’s asset and planning manager for South Texas. “Refracs have become a meaningful part of our development program.”

The goal of its refrac program is not to simply restimulate the existing fracture network, but critically, to break new rock. Post-job analysis using advanced diagnostic tools such as downhole fiber optic sensors demonstrates that the refracs succeed at creating new propped reservoir pathways rather than merely restimulating existing parent fractures. Fiber and downhole gauge data show variable drainage profiles along the lateral strongly tied to refrac-dominant fracture intersections.

Results like these leave no doubt that refracs work from a technical perspective. But are they worth it from the point of view that matters: bottom-line economics?

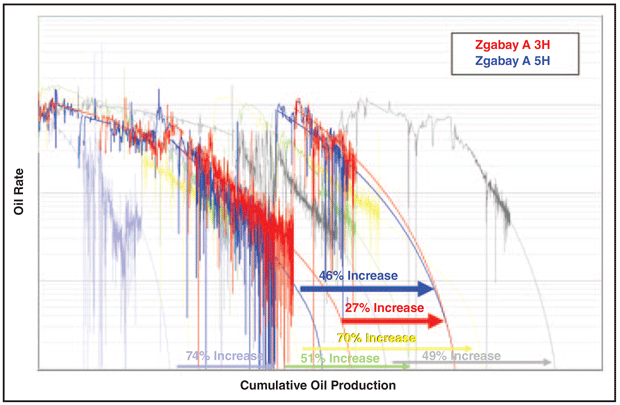

According to Schmitt, the latter question has been settled emphatically for Devon. By significantly increasing EURs at an affordable cost, he explains, its historical Eagle Ford refrac projects deliver strong rates of return. For example, 97%- 250% RORs have been observed at the company’s Zgabay project.

Selection Criteria

To identify the best refrac candidates, Devon Energy has defined specific criteria to evaluate each well’s restimulated upside potential. Initial refrac projects were used as learning opportunities to continuously improve both selection criteria and post-recompletion performance.

“To date, we have done more than 50 refracs all around our Eagle Ford acreage position,” Schmitt reports. “For 2024, we anticipate refracs to continue being a mainstay in our development program.”

And there are plenty more potential refrac prospects where those 70 wells have come from. Devon holds more than 80,000 acres in the core of the Eagle Ford, primarily in Texas’ Karnes and Dewitt counties. The company says refrac projects make the most sense in drilling units that have substantial space between wells, low recovery factors and initial completions with large clusters and much lower proppant concentrations than modern designs.

In a recent study, Rystad Energy found that refracs accounted for 2% of the horizontal well stimulations in the United States through the first nine months of this year, or roughly 200 out of 8,900 total stimulations. Most of the refracs, according to the study, were in the Permian Basin and involved wells originally completed in 2018 or earlier.

Because it offers attractive returns, refracturing wells has become an important supplement to new well completions on Devon Energy’s Eagle Ford acreage. The company has performed more than 50 Eagle Ford refracs and plans to do more in 2024.

While refracs now may be a possibility in all the nation’s shale basins, Schmitt suggests that the Eagle Ford is an exceptional candidate for them. He says there are two reasons refracs are becoming an integral part of Devon’s portfolio. First, the Eagle Ford is mature as shale plays go, so a lot of the mainstay operators in the play are locked into positions they already have consolidated, making it difficult to acquire new acreage, especially undrilled locations in the core.

“We are all looking to how we can maximize our production on our existing positions,” Schmitt reports.

The second reason is the success of the refracs themselves, he continues. “Some of these wells could have EURs between 250,000 boe and 400,000 boe prior to a refrac,” Schmitt offers. “Let’s say a well declines to 10-20 barrels of oil a day and we decide to come in and refrac it. It is typical to achieve a 50% improvement in EUR after refracturing. It is quite staggering to realize how much incremental oil there is in an existing wellbore.”

Resetting The Decline Curve

Schmitt points out that Devon’s refrac wells are producing 70%-80% of the initial production rate after primary fracturing. In essence, refracturing rewinds the production decline curve clock to early-stage well life.

“It is largely an untapped resource,” he says of the incremental oil being produced with the refracs.

That untapped resource is particularly large in the Eagle Ford, Schmitt reflects. “It is such a rich oil-soaked rock per foot, one of the highest of any of the shale basins,” he explains. “It is largely overpressured and the permeability is so low that we have demonstrated there is quite a bit of original oil left in place. The Eagle Ford’s rock qualities have allowed us to pick up plenty of incremental oil.”

There are two main methods of refracs. Bullhead refracturing is pumping down the original casing through the original perfs. Bullhead refracturing attempts to treat the entire lateral in a single stage. On the other hand, mechanical diversion calls for installing a liner to enable multistage completions in the existing lateral.

When Devon’s refrac program was in its infancy, Schmitt says the company deployed the bullhead method, which he jokingly calls “pump and pray.”

“Over the years, we have gotten better at mechanically isolating perforations and we are now fully confident in what refracs can produce,” he relates.

Devon installs a smaller-diameter liner across the entire lateral and cements it in place. Most of its laterals are 3,000-8,000 feet long, depending on the surface leasehold. After the liner’s installation, Schmitt notes that the refrac operation proceeds similarly to a primary frac treatment.

“You pull the current jewelry, prep the well, and get after it,” he states.

Devon typically pumps ±2,500 pounds of sand and 50 pounds of fluid per foot, Schmitt describes, noting that this approach resembles the company’s frac designs for a new-drill treatment.

He estimates that the cost of refracturing a well is slightly more than half the initial cost of drilling and completing the well, meaning that as long as refracs continue to increase EURs by at least 50%, they can play an important role in a company’s program.

Zgabay Project

One parameter that is a little different with refracs, according to Schmitt, is the stage spacing and number of clusters per stage. Many of the best practices Devon employs were developed by participating with a consortium of other companies in the Zgabay Project, which was conducted in 2022 at a U.S. Department of Energy-sponsored Hydraulic Fracturing Test Site (HFTS).

“We went into an existing Eagle Ford unit and drilled a monitoring well,” he says. “Then we drilled a handful of infill wells and refractured two existing wells. It was a robust data collection exercise. We took a horizontal core to measure saturation and get a better understanding of how much oil was still in place.”

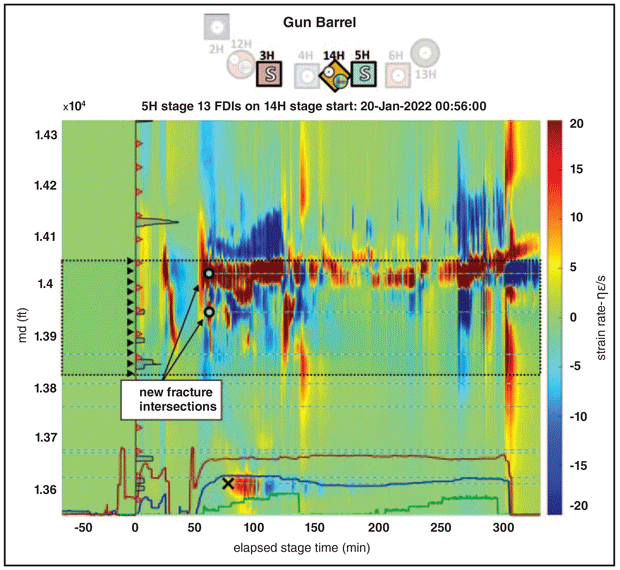

Distributed acoustic sensing data acquired from the horizontal monitoring well confirmed that the refracs created new fractures rather than reactivating existing fractures. Figure 1 shows the DAS data for a specific stage. One refrac increased the well’s EUR 27%, while the other delivered a 46% gain (Figure 2), Schmitt relates. Using fiber optics, the companies were able to get a direct measure of the oil in place in new fractures.

By analyzing the data from the Zgabay Project, Schmitt says Devon has settled on approximately 140-foot stage spacing with seven clusters in each stage. He notes the company now employs the same stage spacing and clustering technique on its new drills.

The Zgabay project followed two earlier HFTS studies in the Midland Basin. It aimed to apply lessons from those studies to evaluate whether refracs could enhance oil recovery in existing horizontal wells.

Both refracs began by installing a liner inside the entire completed perforated interval and mechanically expanding it (or cementing it) to create a seal between the liner and the perforated casing, thereby isolating all the existing perforations from the wellbore. New perforations then were shot in locations between the existing sealed-off perforations, allowing new fractures to be created to reach previously unstimulated rock.

Schmitt calls the success of refracs that use this technique “incredible.”

“The Eagle Ford play sets up so well for refracs because of the rock qualities,” he says. “I have been in this business unit since May 2022. I was aware of Eagle Ford refracs before, but to see firsthand how well they are working is really special. We are challenging our own paradigms.”

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.