U-Shaped Architectures Deliver More Reservoir Exposure, Access To Multiple Benches

By Danny Boyd

The state of the science in horizontal well architectures in shale plays has evolved to an archetypical monobore design with a cased and cemented lateral section extending 10,000-15,000 feet from the horizontal kickoff point. In recent years, the focus has largely been on optimizing lateral lengths, with a number of operators experimenting with ultralong laterals beyond three miles. The Marcellus and Utica shale plays, in particular, have seen one record-setting lateral length after another—culminating last summer in Expand Energy Corp.’s national record of 27,657 feet (5.2 miles) on a Marcellus well in West Virginia.

The industry has become incredibly technically proficient at extended-reach horizontal drilling and getting wells to total depth as efficiently and quickly as possible. But depending on the target reservoir and lease boundaries, drilling longer may not necessarily be better. Instead of extending the lateral farther in one direction, is the next big innovation in well architecture drilling and completing not one, but two “right-sized” laterals going in mirror opposite directions? Twinning laterals from a single vertical is not some engineer’s pipe dream. Multiple projects have already drilled and completed U-shaped or horseshoe laterals in multiple basins.

The next major step change in unconventional technologies and methodologies may have already arrived. Call it Shale 5.0 or some other descriptor for this new paradigm in wellbore architecture, but the name of the game is to maximize the efficiency of infill development, extract maximum value from every asset, and push the cost of each unit of production as low as possible.

Shell drilled the first successful U-lateral in the Delaware Basin in 2019, largely because of lease space constraints. However, a growing number of operators across basins are now embracing this concept to improve development economics and reduce surface footprints.

U-laterals are drilled out from the rig, turned fully in a 180-degree curve, and then drilled back toward the rig again to expose twice as much horizontal reservoir interval in each well. The idea is to maintain hard-won drilling and completion efficiencies and longer lateral lengths while getting essentially a “two-for-one” proposition, with each leg of the horseshoe potentially tapping multiple benches.

Lateral length has historically been limited by three factors: lease boundaries, a point of diminishing return that can vary widely based on well specifics, and the simple fact that the longer the lateral becomes the greater the complexities tend to be when it comes to completing and producing it. While future advancements will no doubt target artificial lift and other solutions for maximizing production and recovery rates over time in both legs of horseshoe wells, the industry’s experience to date leaves no doubt that these wells can be efficiently drilled and completed.

Niobrara Targets

For Prairie Operating Co., drilling U-laterals tapping the Niobrara Shale in the Denver-Julesburg Basin in eastern Colorado allowed the company to target multiple benches with each lateral while reducing the number of wellheads on location, says Todd Wolff, vice president of drilling.

On a company project conducted with the directional drilling expertise of Altitude Energy Partners, Prairie drilled four U-lateral wells on one D-J pad, with each lateral two miles long, extending one mile out and then turning and coming one mile back toward the rig.

Prairie Operating Co. is drilling U-laterals in the Niobrara Shale in the Denver-Julesburg Basin to develop multiple benches with a minimal number of wellheads on each pad. On a project conducted with directional driller Altitude Energy Partners, Prairie drilled four U-lateral wells from one pad, with each two-mile lateral extending one mile out to target distinct zones and then turning and coming one mile back toward the rig.

The U-laterals enabled the company to eliminate the top-hole sections on half of the new wells being drilled, which saved rig time, Wolff explains. Fewer wells also reduced the number of surface separators and other wellhead equipment and reduced pad space, allowing more of the pad to be reclaimed, an important factor in environmentally conscious Colorado. Each lateral targeted distinct zones, enabling multibench development with a minimal number of wells on the pad.

“On all four of our U-wells, we switched between Niobrara Chalk benches,” he explains. “Two of the wells went from the Niobrara B to A and the other two wells went from Niobrara C to B. The benches are each separated by approximately 100 feet of true vertical depth.”

The reduction in the number of wells lowered AFEs and improved rates of return, Wolff goes on. Based on actual drilling costs, each two-mile U-well costs only about $160,000 more to drill than a standard two-mile lateral, he says. The company was able to use the same completion designs as standard horizontals in the basin for stage spacing, proppant concentrations, and fluid loads.

“The exception is that we used dissolvable plugs through the U-turn and on the second lateral,” Wolff reveals. “Also, where the wells crossed in the actual U-turn, we had a section where we did not pump a frac if the wells were within 150 feet center to center, and we did reduce fracs for a few stages.”

Prairie has kept initial productivities close to the vest, but Wolff indicates that well performance has been on par with expectations, even with a bench change between the two laterals, a positive development from a well productivity standpoint. Success has paved the way for future projects, he adds.

“Prairie plans to continue to drill U-wells on many future pads, and we expect to increase the length of the U-wells so we are drilling U-wells with completed lateral intervals of three and possibly even four miles,” Wolff comments.

Learning Curve

Wolff’s previous work on two U-lateral wells for Bison Operating served as a learning curve to improve cycle times on the job, he says. The four wells were drilled with a bottom-hole assembly consisting of a rotary steerable system driven by a mud motor.

In collaboration with Altitude Energy Partners, Prairie deployed SLB’s NeoSteer™ rotary steerable system. The system enabled the company to overcome higher drag friction with minimal impact on penetration rates. It significantly improved drilling times and has proven to be the optimal way forward, especially as the company considers longer laterals, he comments.

But according to Wolff, it is not just one solution that drove the success of the entire project, but the combination of a number of industry advancements in mud motors, RSSs, wireline, dissolvable plugs, coiled tubing, and more.

“All of these technologies require advancements in order to make these wells possible,” he relates. “The mud motors have to be extremely strong and durable to handle the challenging well plans. The RSS is required to ensure the entire drill string is continuously turning to reduce the drag friction and effectively steer the assembly with so much tortuosity.”

Wireline advancements in coated lines and improved sockets were essential for the higher tensile loads to pull the line up the hole, he says. Dissolvable plugs have improved significantly. Coiled tubing sizes in the D-J have increased from 2 3/8- to 2 7/8-inches, with the larger CT stiffer, stronger, and capable of being pushed farther into the wells.

“Without that improvement, we would have to use jointed pipe for the drill outs, which would take significantly more operational time,” Wolff says.

First U-Lateral

Andy Biem, vice president of technical services at Altitude Energy Partners, agrees that improvements in mud motors, measurement-while-drilling tools, and many other systems have made huge contributions to creative lateral design and drilling since Shell’s first U-lateral well a little over five years ago.

Biem, who consulted Prairie on its Niobrara project, was involved in the planning and execution of that first U-lateral. Trial and error back then played a part in adopting systems still used today, he recalls. Aided by computer modeling for U-lateral geometry hypothesized by Shell’s drilling team, the first project started with a rotary steerable BHA, but downhole issues forced a switch to a more conventional bent-motor steerable BHA. Lastly, the team switched to a mud motor-driven rotary steerable BHA, which is what Prairie deployed on its project.

“Back in 2019, we were paving the way and trying to figure out the most efficient way to drill and still protect the downhole equipment,” Biem recalls. “It was a challenge, and there was a lot of learning involved.”

Success marked the beginning of U-lateral design and construction that has been tweaked since then. For example, borehole diameters have expanded from 6 1/8 to as large as 8 3/4 inches.

Supporting innovation includes MWD technology capable of gathering downhole data in real-time, including wellbore trajectory, drilling mechanics and formation characteristics, and transmitting it to the surface. From the outset, MWD systems that provided continuous inclination measurements were critical for U-lateral progress, Biem says. Additional innovations that incorporated a continuous azimuth measurement further increased the accuracy of wellbore placement, he adds.

“With the MWD systems that Altitude employs, we are able to deliver continuous inclination and continuous azimuth from the rotary steerable system as well as the MWD,” Biem explains. “I would not say they are not as accurate as a static survey of the actual borehole, but the continuous inclination and continuous azimuth measurements that we get in real time while drilling are pretty darn close. They are within a few decimals of the static measurements.”

Information is available on the surface for conditions about five feet behind the drill bit downhole. Timely data availability is key in the D-J, where wells can be drilled at rates of 500-600 feet an hour, he says.

“We are able to monitor very closely the wellbore position in real time, and that becomes extremely critical in U-turn wells, especially in the middle of the U-turn itself,” Biem details. “If we are drilling up near a lease boundary, the U-turn is designed to steer away from that boundary and come back to the rig again. Knowing we can get continuous measurements so close to the drill bit in real time through the MWD system enables us to make better and faster directional decisions.”

Mud Motors

Advancements in positive displacement mud motor technologies also continue to accelerate U-lateral drilling and deliver exceptional power to grind through a variety of rock, he says. Mud motors today can churn away with up to 1,000 horsepower. A decade ago, HP was around 400.

Mud motor improvements are a driving force behind growing drilling efficiencies in general in which fewer rigs are drilling more wells, Biem says. While the current rig count of around 550 is about a third of the count in 2014, the amount of produced fluid per working rig has almost tripled over that period, he adds.

“Advancements in mud motors bolster the ability to drill these dimensionally complex wells with more technologically advanced equipment that includes RSS,” Biem expounds. “With the mud motor being the vehicle that is driving that system, those advancements have been a huge game changer in drilling performance.”

Even the RSS tool itself is being iterated on, Biem adds. A decade ago, tools in the U.S. land market were not particularly good at generating predictable doglegs. Today, Altitude continually works with RSS providers on design changes that help generate higher doglegs with consistent, predictable results.

Altitude’s MWD systems interface directly with the RSS and transmit telemetry data to the surface. System innovations include ruggedizing tools or in some cases using a different style of mounting. Altogether, engineered but intentional changes have accelerated U-lateral innovation. The Prairie project required only a single BHA per well drilling the vertical, curve, lateral, U-turn and second lateral, Biem reports.

Advancements in artificial intelligence are also expected to make a difference in helping identify the best solutions for maximizing U-lateral drilling performance. Altitude is working on being able to use real-time data in AI to optimize decision making.

“I am really excited about where downhole and drilling technology are going,” Biem says. “I am a tech nerd myself, so being able to be a firsthand witness of these advancements is amazing.”

High Success Rates

A low failure rate for U-laterals is proof of the efficacy of drilling system advancements that have sped up boring through a variety of rock and enabled successful exploitation of multiple benches through a single well.

“There are a few wells out there that have gone bad, but not very many . . . probably fewer than 5%,” relates John Huycke, who has been involved in 28 U-well projects through his firm Turning Point E&P Consultants. “When it comes to drilling, if only 5% of your wells are going bad, you are doing okay.”

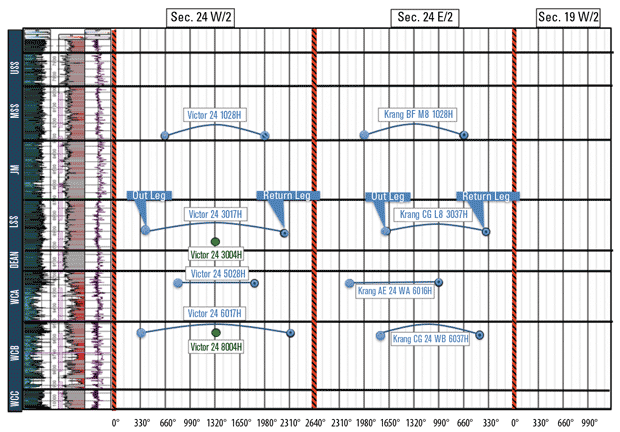

The Victor Pad U-laterals using oil-based mud were drilled in the first quarter of 2025 in the western half of the Section 24 drilling spacing unit. The Krang Pad U-laterals using water-based mud were drilled in the third quarter in the eastern half of the DSU. The single green dots show the two traditional 5,000-foot laterals and the blue dots represent the U-lateral legs. The formation abbreviations denote the Wolfcamp B, Wolfcamp A, Lower Spraberry Shale, and Middle Spraberry Shale.

Huycke estimates from state records that more than 350 U-laterals have been drilled in lower-48 basins, with about 235 drilled in 2025 alone. The Delaware Basin continues to lead the way, followed by the Midland Basin, D-J, Eagle Ford, Haynesville, and Bakken. Projects in the Uinta and Appalachia number in the single digits, according to Huycke’s assessment.

Given the Permian’s preeminence, operators there continue to log successes and innovate. FourPoint Energy in 2025 experienced faster drilling time on a Midland Basin U-lateral pad drilled with water-based fluid, compared with U-laterals on an adjacent pad drilled with standard oil-based mud, says Ben Sellers, drilling manager for the Denver-based company.

Industrywide, water-based mud (WBM) is typically the fluid of choice on most standard unconventional wells, but on U-laterals oil-based mud (OBM) is preferred because of its enhanced friction reduction and other properties, he says.

“As you stretch the well farther, or it gets more complex with doglegs, then OBM is often advantageous over water-based just because of its natural lubricity,” Sellers comments.

Adequate lubricity to minimize downhole friction (thus torque) during drilling is crucial to helping prevent costly pipe wear and damage on both drill pipe and casing. In worst case scenarios, with drill string costs of $2 million, drill pipe wear can become cost prohibitive, says Huycke, who consulted on FourPoint’s project.

FourPoint’s U-lateral drilling project in Upton County was conducted without any major issues and at a significant cost savings, Sellers says.

After drilling its first Midland Basin wells in 2022, the company wanted to drill a single Permian pad with U-laterals tapping the middle and lower Spraberry and the Wolfcamp A and B benches of a single section (640 acres). U-lateral development was executed on two half-section parcels after the company was unable to secure both halves concurrently for standard development. Each half-section was an independent project, with four U-lateral wells to each half-section.

Earlier in 2025, the Victor pad was drilled first with OBM. It consisted of three U-laterals with lateral lengths of 11,200 feet, and excluding the curve, completed lateral lengths averaging 9,700 feet in early 2026. Also drilled were two wells with standard horizontals of 5,000 feet, Sellers details.

Under Budget

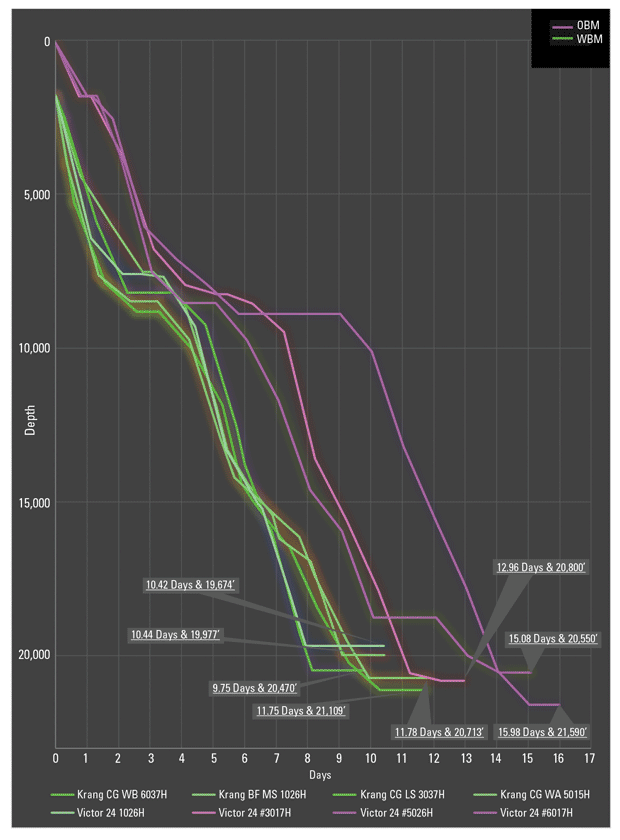

With OBM, Victor U-laterals targeting the Wolfcamp A and B and Lower Sprayberry were drilled in an average of 15 days each and were 21% under budget, he reveals. Two U-laterals were drilled in one run each, with the Wolfcamp A well requiring a pipe trip to recover backed-off tools.

Sound performance with OBM influenced management to test WBM, which the company’s team and consultants on the job have worked with extensively while drilling conventional laterals, Huycke notes. The Krang Pad included five two-mile U-laterals drilled with WBM. Drilling time on the Krang Pad was 10.93 days per well on average.

This figure plots drilling time in days versus depth as a measure of drilling performance for the U-Laterals drilled with OBM on the Victor Pad versus U-Laterals drilled with WBM on the Krang Pad. Overall, the Victor U-laterals were drilled in an average of 15.0 days each while the Krang U-laterals averaged 10.93 days.

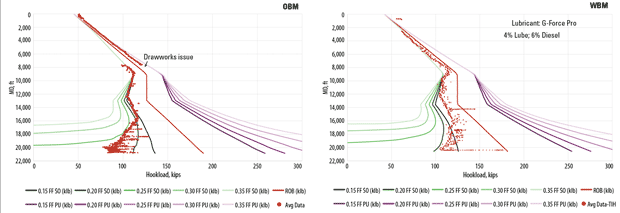

The Victor 3017H (drilled with OBM) and Krang 3037H (drilled with WBM) are both Lower Spraberry U-laterals roughly 1,500 feet apart. These images show the friction factor plot data (dark red circles) from the casing runs on the wells. No rotation was necessary on either casing run, but the Krang 3037H had a lower average friction factor (0.19) using WBM than the Victor 3017H (0.23), which used OBM.

Despite initial concerns about lubricity, drilling with WBM on the Krang pad outperformed drilling with OBM on the Victor pad. The difference equated to a 13% cost improvement, Sellers says. The WBM system included a mix of lubricants and some diesel. While OBM mud was kept on site in the event WBM performed poorly, it was not used.

Four of the Krang wells were drilled in one run, with a Middle Spraberry well requiring a trip to replace a drill bit.

“We saw a 27% improvement for just the time that it took,” Sellers reveals. “We were 27% faster with WBM, which is counterintuitive, but we used WBM second, so all our learnings were on OBM, and we were able to do some fine tuning on the WBM system.”

The same bits, BHAs, and motors were used on both pads and all casing went to the bottom on both projects. Casing runs on the first two Krang U-laterals required some rotation while latter wells with more accumulated lube in the hole encountered less friction and strings were lowered without rotation, Huycke points out.

On both projects, savings equated to 19.5% compared with AFEs, Sellers reports. The cost of drilling one U-lateral was estimated at 40% less than the cost of drilling two traditional one-mile laterals, he adds.

The project required extensive preplanning that included discussing options with fluid experts to devise the lubricant package. The process helped identify what kind of connections were needed on casing and drill pipe, and necessary torque ratings for the rig’s top drive and iron roughneck, according to Huycke. Tortuosity management on the job was exceptional, he says.

Preplanning also included validating friction factors in models. Friction factors showing the resistance between the drill string and the wellbore can vary widely between OBM and WBM fluids, but the numbers for both were remarkably similar in some cases, Sellers says.

On the Victor Pad, OBM had friction factors from 0.21 to 0.23, and in some cases, a little lower. Torque and drag modeling with a 0.15 friction factor predicted about 25,000 pounds of torque, which on subsequent wells declined by several thousand pounds. With the WBM, the factor eventually lowered to 0.23 on average and 0.19 as a standout example, Sellers notes.

At-bit sensors to measure downhole weight, torque, gyro, vibration, temperature, and other factors provide plenty of data for review in the coming months to get a more in-depth technical view of comparative performance and performance by bench, he concludes.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.