Automation And Better Pumps Reduce Lifting Costs

By Colter Cookson

With the right expertise, production engineers can adjust existing artificial lift equipment to reduce cost per barrel. Whether the savings come from increasing production, extending mean time between failures, or minimizing electricity consumption, they can add up if similar optimizations are applied to every well.

But it’s generally impossible for even the most efficient and skilled production engineer to spend time improving every single well. At many companies, each engineer oversees 200-600 wells, with some overseeing more than 1,000, reports Chris Robart, chief commercial officer at Ambyint.

“No one can effectively manage that many wells with manual processes,” he says. “Each of these wells has a whole bunch of data sets and time series that need to be analyzed to understand what is going wrong and what is going well. That analysis takes so much time that in general, production teams only look at wells when production starts falling short of plan. By that point, the well likely has a big problem, not a small one that is easy to correct.”

If engineering teams had the time to check wells consistently and keep wells in stable condition, they could improve production and prevent problems that ultimately require site visits and other, costlier interventions. According to Robart, that is where AI comes into play.

“AI is great at automating clear, procedure-driven workflows,” he says. “By using it to automate some well surveillance workflows and routine optimizations, we can get production and operations teams out of reactive mode and into a more proactive mode.”

To illustrate how effective automating well optimization can be, Robart points to an operator in the Bakken that began using AI for rod lift wells in 2020. The company maintains detailed records on “well touches,” or situations where the production team has to interact with the well. Those range from inspecting the well using SCADA systems to visiting sites.

“The number of overall well touches went down by 40% after the operator adopted AI,” Robart says. “For site visits, the reduction was even higher at 50%. Employees spent less time driving and more time doing meaningful work.”

That Bakken operator also increased average oil production by 15% while reducing pump strokes per minute by 10% and detrimental rod compression events by 23%, Robart adds.

The Bakken operator’s experience mirrors that of many other operators, Robart says. For example, Chord Energy achieved a 7% increase in oil production, a 28% decrease in strokes per minute and a 38% reduction in failure rates after adopting AI to manage rod lift wells in the Bakken.

In the Appalachian Basin, Encino used the platform for plunger lift wells. The AI helped the company increase on-time plunger arrivals by 14%, reduce annual production declines by 1%, and slash venting events by 62%, Robart shares.

Industry Partnerships

Through a partnership with ROAM-AI, Robart says Ambyint is also helping clients improve the performance of their ESPs.

To justify investing in autonomous optimization, Robart says operators typically need a couple hundred wells that are geographically concentrated. They also need a SCADA system from which AI can retrieve data.

“From a model development perspective, we have stayed away from any need for fancy new sensors or on-site hardware,” Robart says. “We focus on building models that can deliver value from the data most operators already collect.”

To develop its AI models, the company pairs artificial lift experts with data scientists. While the models for some tasks rely exclusively on AI, Robart says the majority constrain the AI using physics.

“We use physics models to tell the AI the current state of the well and the range of scenarios it can play in,” Robart says. “The AI isn’t making wild guesses based on data alone. It’s got some intelligence and prediction behind it to figure out what could move the well in a better direction.”

Robart acknowledges that even the best physics models can only provide a sketch of the downhole environment. “At least in the onshore world, most wells are managed primarily from surface sensors. There are a lot of miles between the surface and what’s happening downhole,” he notes. “Physics can bridge the gap between what the surface sensors show and the downhole realities, but many variables, such as multiphase flow, keep physics-only models from capturing a perfect picture.”

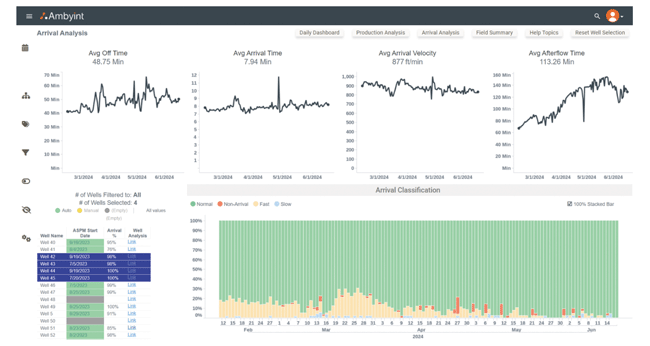

Production teams that use domain-specific AI to continuously optimize their artificial lift systems see several benefits, including higher production, less strain on equipment and earlier warnings about potential issues, Ambyint reports. For plunger lift, the production increase typically ranges from 3% to 7%. This screenshot shows arrival analytics for several plunger lift wells for which AI is managing set points.

Fortunately, the AI can spot patterns that would not be obvious based on physics alone and identify changes that are likely to improve well performance within an area. In general, Robart says the company’s AI models begin making recommendations within five to seven days of connecting to the SCADA system.

“A few operators will jump to autonomous control as soon as that connection is done, but the vast majority want some time to validate the models,” Robart notes. “During that period, the models will generate recommendations that the production team can manually implement with the press of a button. However, the goal is to get them to autonomous control mode as quickly as possible, because it has much larger benefits.”

Economic Perspective

There is still plenty of room for AI-driven optimization to improve, Robart reflects. “One of the things we are working on is incorporating economic data more robustly into the platform,” he says. “That will let us consider more factors during optimization and help operators track their cost per barrel from field to field and well to well.”

The company is also investing in developing a mobile app for its platform. “We get consistent feedback from operations stakeholders that they prefer to work on mobile devices,” Robart explains. “Delivering a mobile application and a mobile experience should improve user engagement with folks in the field.”

Robart adds that Ambyint is commercializing its gas lift optimization models. “Gas lift has seen significant adoption as an initial form of lift in areas that have traditionally started with ESPs, including the Permian, Anadarko, Eagle Ford and even the Bakken,” Robart says. “Many of today’s new wells are really gassy, so gas lift is becoming an increasingly important part of the artificial lift portfolio within North America.”

Electric Gas Lift

Growing gas lift adoption has helped drive interest in electric gas lift systems, says Alex Moore, team lead for the electric gas lift product line at Precise Downhole Solutions. “Electric systems excel in new unconventional wells that have high initial rates and fast drawdowns,” he says. “The systems can keep up with changing downhole conditions and the range of production rates they will encounter.”

That adaptability comes partly from automation, which Moore says is quite sophisticated. “It can kick off a well, unload a well and provide stable injection as the well is producing. It adjusts injection depth based on downhole and surface parameters. It’s always injecting at the lowest point possible, which improves production.”

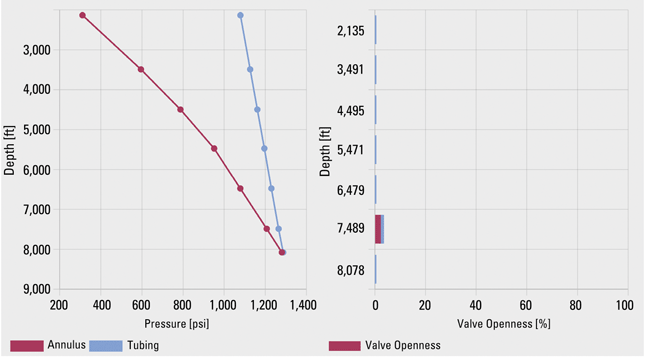

Electric gas lift valves boost production by allowing users to take full advantage of their injection pressure and automatically injecting at the deepest point possible. But according to Precise Downhole Solutions, their biggest benefit in high-rate unconventional wells is support for bidirectional flow, which lets users switch from producing up the annulus to producing up the tubing without a workover. This screenshot shows the control screen for the company's electric gas lift system.

Moore adds that the system maintains the ideal orifice size: as small as possible while still achieving the desired injection rate. “If the well starts to slug and the orifice is too large, that can lead to big fluctuations in the amount of gas moving across it. But if the orifice is small, the rate will stay the same. This helps provide stability in the well,” he explains.

Decisions about which injection depth and orifice size to use are made by a unit at surface that is powered by a small solar panel, Moore describes. “Today, this unit uses the data our electric valves collect to achieve an injection rate set by the flow controller,” he says. “With time, our system will be able to determine the optimal gas injection rate by itself.”

Reducing Workovers

While continuous optimization has significant long-term benefits, Moore says the biggest appeal of EGL systems is their ability to eliminate the workover or wireline run traditionally needed to switch from annular to tubing flow. Moore says this change, which occurs once production rates fall below the threshold where the extra space in the annulus is beneficial, merely requires swapping a few valves at surface.

That surface-based transition is possible because EGL eliminates the need to install and then remove check valves downhole. Normally, check valves would be necessary to prevent gas from flowing back into the tubing during annular flow. However, Moore says the electric valves have onboard pressure and temperature sensors on each side that allow the automation to calculate the differential pressure across each valve, detect when backflow could occur, and close the problematic valves.

The immediate savings from eliminating the initial workover coincide with long-term production gains, Moore says. “There is an inherent production benefit from using electrically operated valves rather than ones that open based on injection pressure,” he says. “With an injection pressure-operated valve, it’s only possible to inject at a deeper point by reducing the injection pressure. With electric valves, the well can always use the maximum injection pressure, which allows it to inject deeper and achieve a lower flowing bottomhole pressure.”

Reliability

When operators evaluate whether to invest in EGL, one of their biggest concerns is reliability, Moore says. “Precise has installed hundreds of valves across six years, so we have had the opportunity to refine our hardware and automation software. With the latest iteration of our tools, we are seeing multiyear runtimes,” he assures.

In many applications, Moore says the tubing will need to be pulled and replaced long before the electric valves fail.

“For high-value wells where failure would be particularly problematic, we have developed a mechanical redundancy option,” he mentions. “Instead of mounting valves on our standard mandrels, we put them on ones with an integrated sliding sleeve. If a valve fails, the operator can intervene in the well to shift that sliding sleeve and either seal an open valve or uncover an auxiliary port.”

Aside from reliability, Moore says EGL cost is a concern for operators. To minimize unnecessary spending, he says his team works closely with customers to determine the best valve count and placement.

“Because gas lift design has always been based on injection-pressure-operated valves, people make assumptions without realizing they are,” he says. “Electric valves have different characteristics that we need to take into account.”

For example, it’s vital to remember that electric valves support both annular and tubing flow. “Placement becomes very important,” he says. “For the bottom valve, we need to consider where gas will exit the tubing during annular flow and where it will enter the tubing during tubing flow. For all the valves, we try to place them where they will provide the most value.”

With experience, Moore says identifying the most cost-effective placements has become easier. “From past installations, we know which valves tend to be underutilized or overutilized in each mode,” he explains.

Over time, Moore predicts that the cost for each valve will fall as EGL gains popularity and suppliers increase volumes.

ESPs

To handle associated gas, operators are asking ESP designers for systems with higher gas tolerances, says Pavel Sviridov, director of technology for Levare US. “We see more and more demand for gas management,” he says. “That means improving the design of gas handling stages, gas pumps and gas separators.”

With modern designs, Sviridov says ESPs can tolerate high gas-to-oil ratios. “A pump with mixed flow stages may be able to handle 25% free gas by itself. If it’s protected by a gas separator and a gas handling pump, that percentage could go up to 90% or 95% free gas,” he illustrates.

The percentage will vary based on factors such as the flow rate and pump intake pressure, and Sviridov points out that slugs are more difficult for ESPs to handle than free gas. However, he says gas tolerance continues to improve.

One of the challenges of gas relates to the motor lead extension (MLE), the cable that connects the ESP’s motor to the power cable. Because the MLE runs along the ESP, it is usually smaller and more robust than the rest of the cable. However, it still needs to be cooled to prevent overheating. Under normal circumstances, Sviridov says the fluid that moves through the pump should provide adequate cooling and keep the pump’s operating temperature at an acceptable level.

“However, in high gas, low flow rate environments where the fluid velocity is low, that cooling is no longer as effective,” Sviridov cautions. “If the pump gas locks, it will temporarily stop moving fluid altogether, and for a very short period, the temperature inside the pump could rise to 600 or 700 degrees Fahrenheit. Since the MLE is attached to the ESP, that temperature increase is enough to melt the MLE’s insulation and lead, which will cause a failure.

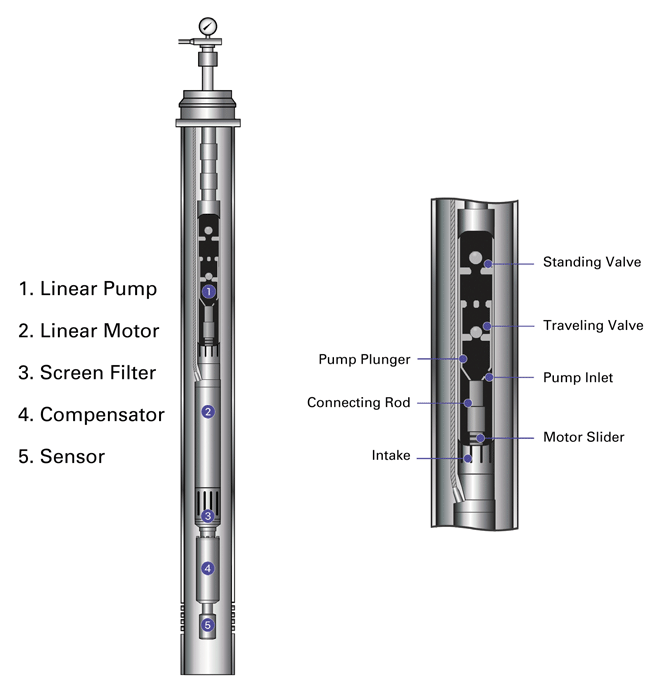

Linear electric submersible pumps can be an attractive option for handling low flow rates from deep wells with sharp curves that would put considerable strain on a rod string, Levare says. They also shine when operators want to minimize their footprint or noise at surface.

“To minimize the chance of that occurring, we can use adiabatic tape to create a protective layer between the MLE and the rest of the equipment that limits how much heat can transfer to the MLE,” he says. “This tape has significantly increased ESP run life.”

To show how significant the improvement can be, Sviridov recalls an ESP that would fail on average every 150 days because its MLE would melt. As of early January, that pump has run more than 600 days without MLE issues, he says.

Low Flow Rates

The industry’s need for greater gas handling extends to ESPs for flow rates below 1,000 bbl/d, Sviridov reports. “For more than a decade, low-flow pumps have typically used radial or hybrid flow stages, which are not good at handling free gas,” he says. “We have developed a mixed flow stage that can move almost twice as much free gas as radial ones.”

The mixed flow stage enables gas-tolerant pumps targeting flow rates between 300 and 1000 bbl/d, Sviridov says. As of early January, Levare was conducting final lab tests and preparing to move these pumps to field trials, meaning they could be available as early as the second quarter.

For even lower flow rates, Sviridov says Levare has invented an alternative to traditional ESPs that can produce as little as 20 barrels a day efficiently. Called Linear Electric Submersible Pumps (LESPs), these pumps move fluid using a plunger, much like a rod pump. However, this plunger is on top of a submerged motor rather than being driven from the surface.

“There is no rod string, so LESPs are great for deep wells with high curvatures that cause rod strings to fail quickly,” he says. “They also work well in areas where a pumpjack would take up too much space on the surface or make too much noise.”

So far, most of the deployments have been in California. “There is potential in other areas, but we need to adapt the system for deeper applications and higher flow rates,” Sviridov comments. “For example, clients in the Permian usually ask for flow rates from 200 bbl/d to 500 bbl/d at setting depths between 8,000 and 10,000 feet. The existing designs can provide up to about 250 bbl/d, but only at 5,000-6,000 feet.”

That is changing. “We are in the final stages of testing a higher horsepower system,” Sviridov shares. “The first systems will be available sometime this year.”

Safety Enhancement

Power efficiency can have a huge impact on an ESP’s operating costs. In areas with power constraints, it also determines how many pumps an operator can run. With that in mind, Sviridov frequently recommends using ESPs with permanent magnet motors rather than induction motors.

“With an induction motor, the efficiency and power factor drops rapidly once the load falls to 60% of the capacity and below, meaning that much of the power the motor consumes is wasted rather than being used to operate the pump,” he cautions. “A PMM has higher efficiency (up to 93%) and a constant power factor across its entire range.”

That translates into much lower power needs. “We have seen situations where operators would be limited to five induction motor-driven ESPs because of power constraints. With PMMs, they can run one or two extra ESPs within the same constraint,” he demonstrates. “Using PMMs also helps clients reduce their electric bills by 10%-20%, depending on the operating conditions.”

Sviridov adds that PMMs generate less heat. “This is important in high-gas, low-flow environments,” he says. “As a rule of thumb, an induction motor needs fluid to move past at a velocity of around one foot per second to stay cool. A PMM only needs a bit of fluid.”

While PMMs provide many benefits, they require greater awareness of electrical exposure considerations for surface crews during ESP installation or retrieval. If the pump and motor assembly’s shaft rotates unexpectedly, a phenomenon called backspin, it could generate a potentially lethal voltage and current in the power cable, Sviridov warns.

To prevent that, Levare has adopted the best practices for handling PMMs outlined in API RP 11S9 and has further developed its own guidelines aligned with the API. Levare was one of the core contributors to development of the industry recommended practice, Sviridov notes.

Sviridov says Levare has also created a tool that monitors the cable to detect potentially dangerous electric currents. If it picks up such currents or anomalous downhole pressure conditions, it issues audible and visual alarms alerting personnel in the vicinity about a potentially hazardous backspin condition.

Because the monitor operates throughout the run, it eliminates the need to periodically stop the cable and manually check it for currents and insulation integrity. “This minimizes how often field personnel need to interact with the cable and electric parts, providing better safety for everybody,” Sviridov says. “It also speeds up the installation, which reduces costs by allowing the company to use rig time more efficiently.”

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.