Resource Plays Spur Big Infrastructure Rebuild

By Tom Seng

TULSA–The shale gas bonanza has brought large-scale changes to the North American natural gas market, the likes of which have never been seen before, from both a pricing and infrastructure perspective.

On the infrastructure side, the impact has been twofold. First, there was the sheer volume of the gas from the mostly dry fields in the Barnett, Fayetteville, Haynesville and early Marcellus that had to be transported to market.

Then, after that abundant supply drove down prices, producers quickly shifted their emphasis to wet gas, seeking the pricing “uplift” from the liquids content. Numerous wet gas and tight oil plays were developed, including the Marcellus, the Eagle Ford, Bakken and Utica. This has led to a new wave of liquids infrastructure needs for gathering, processing and transportation.

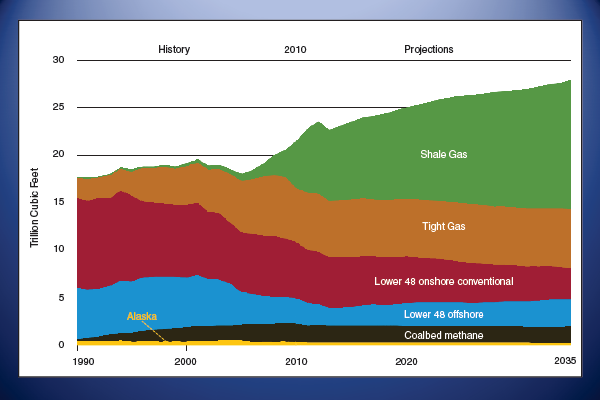

FIGURE 1

Natural Gas Supply by Source (Tcf)

Source for figures: U.S. Energy Information Administration

It is difficult to overstate the magnitude of the volumes of natural gas and liquids, and the billions of dollars of investment in infrastructure to process and transport this new production to market. Data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s 2012 Annual Energy Outlook show shale gas accounting for half of the country’s total natural gas supply of about 27 trillion cubic feet by 2035 (Figure 1).

An important factor in the demand for new infrastructure related to shale plays is that most new fields were not in traditional producing regions, where access to markets was readily available. This, of course, meant it was necessary to build the entire support infrastructure–gathering, processing and transmission–from scratch.

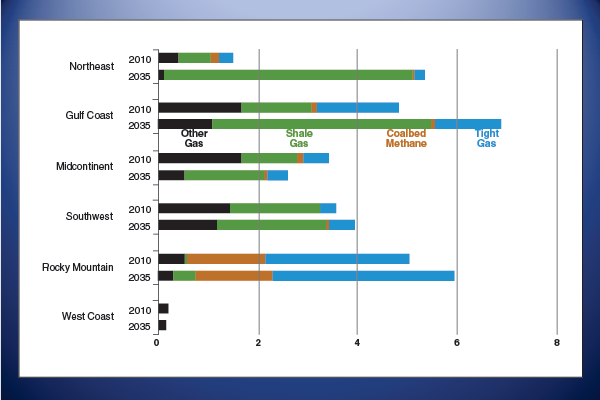

In regions with a history of gas production, the new volumes often overwhelmed existing capacities, creating gas-on-gas competition for pipeline capacity. In all, the basins where gas was flowing did not correlate well to the regions where processing and transportation was available (Figure 2).

Take-Away Capacity

Behind the obvious trends and evolving investments, there are also several more subtle developments. One is that, for stranded gas, take-away capacity is vital, and net-back pricing, in some cases, has become a secondary consideration, as surprising as that may seem. As noted, many shale plays are located in regions that either did not have transmission pipeline infrastructure in place, or had insufficient (outdated and undersized) infrastructure. Since they were deemed “unconventional” resources because of the nature of the formations and the difficulty extracting the gas, there had been no need to build pipelines.

Once technological advances changed that, producers urgently needed take-away capacity. Lacking the infrastructure, they began working with the pipeline companies to have pipe built to get their gas to market. And, with no competing pipelines at the start of most of these shale plays, producers had to commit to long-term, firm transportation capacity to justify building the pipe. As such, they had to accept the rates approved by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

Producers are committing to capacity, and therefore, effectively are backing these pipeline projects financially. Any new pipeline project must have shipper commitments to obtain approval, but it is occurring on a larger scale in North America today because of the proliferation of shale gas and tight oil plays.

Another change in market dynamics brought about by shale gas is the expansion of producers as pipeline shippers. With the advent of FERC’s infamous Order 436 (the “open access” rule) in 1985, transportation and storage capacity moved largely into the hands of marketing companies who “rebundled” the traditional services offered by the pipelines themselves. They now would buy, transport, store and sell the gas, offering more competition than the franchised monopolies of the pipelines.

But with the advent of shale gas, it became the producers who sought take-away capacity in the form of new transmission infrastructure. They had the production and the need, and were willing to pay what it would take to move their gas to market.

The producer-as-shipper was almost nonexistent until the Barnett Shale in the Fort Worth Basin started producing. XTO Energy (now Exxon/XTO) anchored a pipeline project to get its gas from Carthage, Tx., to the Perryville Hub in Northwest Louisiana. That really started the pattern of producers in these new shale plays going directly to the pipeline companies. A similar pattern would follow in other “stranded” shale plays such as the Fayetteville in Arkansas.

This same scenario has played out several times throughout the country in shale gas-producing areas that lacked pipeline capacity. The trend is not going away anytime soon. If there are new shales found in remote locations, producers will have to back new pipeline capacity to get their gas to market (the Bakken Shale faces that dilemma, since a substantial amount of the gas associated with the oil production is being flared while awaiting additional midstream infrastructure).

Effect On Spreads

An interesting side effect of this shift in transmission pipeline customers, and tighter locational spreads, has been the negative impact on many marketing companies. Producers shipping their own production are replacing that traditional marketer function. And some marketing companies are no longer finding it economical to pay the monthly reservation fees to subscribe to firm transportation capacity, especially when rates are higher than actual spreads. In fact, already some marketers are releasing pipeline capacity back to the pipelines for resale.

Additionally, the market is starting to experience a lack of “recontracting” when transportation agreements expire, especially for the traditional long-haul pipelines moving gas to the Northeast and upper Midwest. As an industry, we have never seen anything like this before: so much gas being produced in excess of demand. That has reduced transportation spreads greatly, causing a disincentive for shippers to renew agreements on expiration, or at least, to do so at the former rates.

The Rockies Express pipeline is a prime example of a largely producer-backed pipeline whose spreads later shrunk as a direct result of the Marcellus Shale. Not only are many of those same producers not renewing their transportation agreements, but gas is flowing east-to-west on REX from the Marcellus to Midwest markets such as Chicago.

In order to maintain a level of constant revenue, some pipelines are competing with themselves, offering “short-haul” and “back-haul” services considerably cheaper than their traditional long-haul rates. For example, the Williams Companies’ Transco Pipeline offers a back-haul service to take Marcellus gas in Pennsylvania to markets south of its traditional Northeast service territory. Gas coming from that direction competes directly with Gulf Coast supplies, which flow at traditionally higher “forward-haul” rates.

A problem then occurs when their major shippers’ contracts expire. How much of their Gulf Coast-to-Northeast capacity will shippers abandon in favor of the short-haul, lower-rate Marcellus supply? Spectra Energy’s Texas Eastern Transmission Company has proposed projects that actually would bring Marcellus gas not only to the Southeast, but also down to the Gulf Coast.

With the potential for untold amounts of traditional long-haul natural gas pipeline capacity being abandoned, the question has to be raised of overbuilding infrastructure. This leads to one of the most interesting contrasts in this evolution of transmission build-out. Anchor shippers needing take-away capacity are backing the new projects, such that there is no “overbuilding,” per se (FERC does not permit speculative pipeline projects).

At the same time, these shipper commitments to new capacity may mean that existing pipelines lose shippers, thus creating the irony of unused capacity at the same time new capacity is being constructed.

This speaks to the situation whereby the pipelines being built (or that will be built) to move shale gas to market will have long-term commitments to finance their construction and serve as justification for FERC sanctioning. Since the producers are supporting these new projects financially, they are not determined to be “unnecessary.” Not only are these new pipelines transporting shale gas, but unless an existing pipeline can serve the areas (such as the Tennessee, Transco and Columbia lines in the Marcellus), traditional pipelines lose out on this opportunity.

There will, no doubt, be several interstate pipeline companies lined up at FERC’s door to discuss this dilemma and seek a solution. If transportation spreads are too tight for these pipelines to remain profitable, and with the exit of some marketers/shippers, could FERC allow the pipelines to return to some level of merchant service out of necessity?

Market Premiums

Another impact of the new supplies and subsequent infrastructure expansions is that premium markets are losing their premium, in some cases. Using the Marcellus as an example, a huge amount of supply now exists in the backyard of the Northeast, the highest-priced natural gas market in the United States As a result, supplies for the Northeast are cheaper from all sources, and this dynamic will not change. Prices in the Northeast will lose more of their premium as more gas is produced, especially with the addition of Utica Shale gas. This will continue to reduce the spread from the Gulf Coast and Midwest to the Northeast, further exacerbating the transportation situation.

An issue closely tied to this supply growth and transportation capacity is demand. There has been a great deal of speculation about the growth of existing and new consuming markets. While there has been an increase in industrial and manufacturing activity, fertilizer production, and coal-to-gas switching in electric generation because of lower natural gas prices, the consensus remains that the U.S. economy is still struggling.

More specifically, demand certainly has not kept pace with supply since the 2008-09 recession, and any coal-to-gas switching in electric generation has proven very price sensitive and is subject to constant change.

As long as oil prices remain high, natural gas liquids prices will remain high enough to give producers of rich gas an uplift on total Btu value. So, while New York Mercantile Exchange futures prices appear to be moderate (and they are for dry gas), the total revenue on an MMBtu basis is very high for wet gas volumes. This should continue to keep plenty of supply on the market over the intermediate term.

Rail Transportation

While gas led the shale revolution, oil has prompted another major shift in transportation and infrastructure: the need for transportation by rail where pipelines are either not in place or lack available capacity. Unit-train loading operations started as a necessity to get stranded Bakken barrels to market, but the role of rail systems has expanded dramatically in shipping both crude oil and refined products.

According to an EIA report issued in July, with U.S. at its highest level in two decades, the industry is relying more on railroads to move oil to refineries and storage centers. Citing statistics from the , EIA reported that 356,000 carloads of crude oil and refined products were transported by rail during the first half of 2013, which was up 48 percent from the same period in 2012. With one rail car containing roughly 700 barrels, 1.37 million barrels a day of oil and refined products was shipped during the first half of 2013, up from 927,000 bbl/d during the same period in 2012.

Natural gas is obviously not a fit for rail, but many of the new loading terminals are being built as hubs for multiple hydrocarbon lines in and out. Rail will continue to be used until substantial pipeline infrastructure is built for both crude and NGLs. Given the flexibility provided by rail service, there is some thought that rail service will remain and that pipelines may not ever be built in cases such as the East Coast and even in the Bakken/Three Forks.

Some of that crude oil is making its way to the Northeast by rail, where pipelines could have delivered it south to Cushing, Ok. A $2 billion crude line was proposed from the Bakken to Cushing, but it did not get enough interest and ultimately was scrapped. Rail transport of NGLs likely will be only a temporary situation while the many proposed pipeline projects get built. Some of those will convert natural gas pipelines to carry NGLs, which will not only help expedite the projects, but also will take advantage of underutilized capacity.

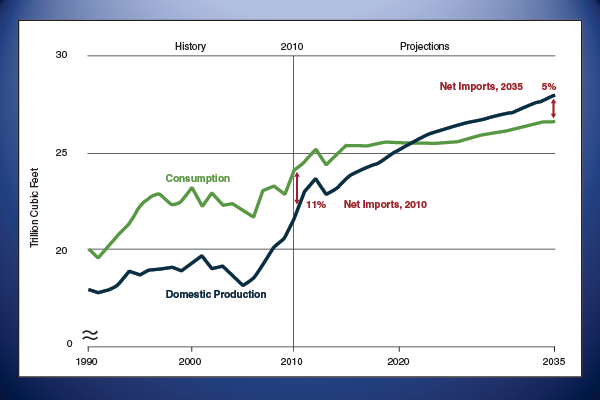

The debate over what to do with America’s new natural gas bounty is being played out (Figure 3). Several consuming sectors are expanding, from transportation to steel-making, and from paper mills to gas-to-liquids facilities.

Analysts predict that resurgent demand by industrial users will add up to 5 billion cubic feet a day in industrial gas consumption by 2018. The petrochemical and fertilizer sectors are expected to account for the lion’s share of that growth, but with hundreds of new industrial facilities planned over the next five years, other industrial users are expected to increase consumption as well.

One example is steel manufacturing. Several new-build plants and facility upgrades that will burn natural gas instead of coal are in various stages of construction across the country. The list of new steel-making facilities includes a Voestapline plant near Corpus Christi Bay, Tx., a Nucor plant in St. James Parish, La., and a Vallourec and Mannesmann plant in Youngstown, Oh.

Even with increased domestic demand, however, the export market looms as a major opportunity, especially for liquefied natural gas, despite its huge capital costs and political and environmental opposition. When the United States starts to export LNG, it actually will represent a new market for natural gas, and not simply an increase in an existing one. Several LNG export projects have been approved both in the United States and Canada, with exports scheduled to begin as early as 2015.

A final point to consider as the natural gas infrastructure continues to expand to bring more supplies to market is the potential for developing regional market pricing hubs. Gas prices could, indeed, become “regional.” That is, with tighter spreads among regions, we could see regional prices emerge instead of so many location-specific pricing points.

For instance, there might be a “Midwest price” that would include parts of Kansas, Oklahoma and Missouri. Other price hubs could be East Texas and Louisiana combined, all of West Texas and New Mexico, and even a Rocky Mountain price that covers Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and North Dakota. We will have to see what the market dictates, but such a development certainly is an intriguing possibility.

Tom Seng is the manager of product marketing at Superior Pipeline Company in Tulsa. He is also an adjunct instructor in energy commodities at the Collins College of Business at the University of Tulsa, the M.J. Neeley School of Business at , and . He has more than 30 years of industry experience in physical and financial commodity trading, transportation and storage services, risk control, gas purchases and sales, business development, and interstate pipeline operations. Previously, Seng served in various positions at Rely Energy LLC, BME Energy Consulting, Atlas Pipeline Mid-Continent, Ozark Gas Transmission Company, ONEOK Energy Services, and PanEnergy Trading. He holds a B.S. from the State University of New York College at Oneonta, and an M.B.A. in international oil and gas management from Robert Gordon University in Scotland.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.