Restoring Venezuelan Oil Production Would Require Huge Investment

Events in Venezuela are likely to have a limited near-term impact on oil markets, according to natural resource investment firm Goehring & Rozencwajg.

“Venezuela does, without question, possess enormous oil reserves—roughly 220 billion barrels by most estimates, enough to place it at the top of the global reserve table—but the act of converting those reserves into sustained production has always been, and will remain, an undertaking of formidable scale,” the firm writes.

That is partly because most of Venezuela’s reserves are heavy, meaning the oil has partially oxidized underground and become difficult to move. “Complicating matters further, Venezuelan heavy oil is also notably sour, containing elevated sulfur content,” Goehring & Rozencwajg continue. “This characteristic demands specialized handling at the wellhead and equally specialized equipment at the refinery. The process, taken as a whole, is intricate, capital-intensive, and unforgiving of neglect.”

How Neglect Happened

Citing the BP Statistical Review, Goehring & Rozencwajg say Venezuela’s oil output peaked at 3.8 million barrels per day in 1970, then began to decline as conventional production fell. In the late 1980s and 1990s, production recovered thanks to Western investments in heavy oil projects. By the end of the 1990s, it had reached 3.5 million bbl/d, Goehring & Rozencwajg relate.

“When Hugo Chávez came to prominence in the early 2000s, Venezuela moved to nationalize its oil assets, prompting most Western producers to withdraw,” the analysts note. “The national oil company, PDVSA, then experienced a debilitating strike in 2002–2003, which sharply curtailed production. After the strike ended, output staged a temporary recovery, reaching approximately 3.3 million barrels per day by 2006.

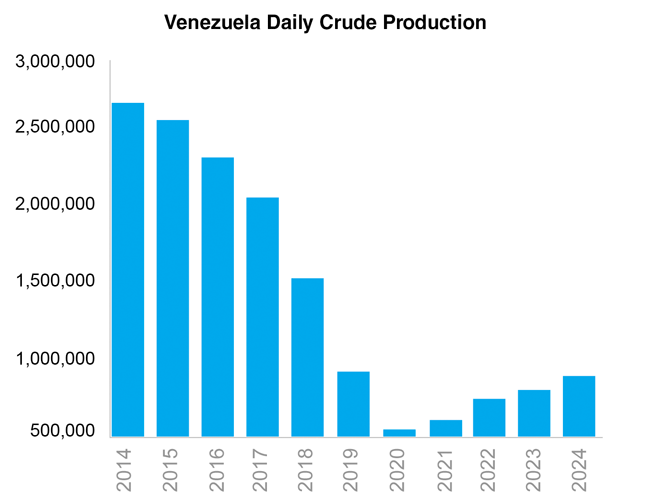

“That year marked another turning point: contracts were rewritten or voided, capital spending collapsed, and skilled labor began to leave the country,” Goehring & Rozencwajg say. “By 2015, production had slipped to 2.8 million barrels per day, before entering a far steeper decline. According to the most recent IEA data, Venezuelan production now stands near 800,000 barrels per day—nearly an 80% drop from levels seen in 2000.”

Barriers to Revival

As Venezuela plunged into severe poverty, Goehring & Rozencwajg say much of the infrastructure installed in the 1990s and early 2000s was dismantled or stripped for scrap.

“Restarting Venezuelan heavy-oil production would require capital investment on an extraordinary scale,” the firm argues. “As one illustrative example, an older industry document indicates that supermajors spent approximately $23 billion in 2010 to bring 600,000 barrels per day of heavy-oil capacity online—roughly $40,000 per flowing barrel. More recent rules of thumb for Canadian heavy oil suggest figures closer to $100,000 per flowing barrel, implying that adding one million barrels per day could require on the order of $100 billion once the cost of an upgrader—an essential component of heavy-oil production—is included.”

Venezuela production has fallen from 2,675,000 MMbbl/d in 2014 to 893,470 thousand barrels per day in 2024, according to EIA’s latest annual production data.

Given the upfront costs, the firm says it would be difficult for Venezuelan heavy oil projects to generate a 10% return on investment, let alone the higher ROIs needed to justify putting capital in an area with considerable geopolitical risk.

“We estimate that $70 per barrel would be the absolute minimum required to bring back online 200,000-300,000 bbl/d of brownfield production and generate a 15% rate of return,” Goehring & Rozencwajg say. “To bring on anything more than that would likely require WTI to trade for $90-100 per barrel, and take several years.”

Rystad’s View

In a report estimating how much capital Venezuela would require to boost its production back to 3 million bbl/d, Rystad Energy puts the total investment over 15 years at $183 billion. For context, the firm says that number is close to the current annual capital expenditures for upstream land opportunities across North America. Breaking the total down, Rystad says $102 billion would go to upstream costs, with the remainder focused on pipelines, upgrades and other infrastructure.

While such a production rebound is technically feasible, Rystad suggests that drawing the requisite capital would require sweeping changes. “A complete revamp of local governance and legal frameworks in Venezuela, accompanied by U.S. government guarantees and support, along with a potential restructuring of PDVSA and changes to the Organic Hydrocarbon Law, will be necessary to trigger initial interest,” it writes. “Even then, it remains unclear how further geopolitical risk and the ongoing ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips legal disputes would influence investment appetite.”

If that investor appetite exists, Venezuela has some near-term opportunities. For about $14 billion, Rystad says the industry could raise production by 250,000-300,000 bbl/d over the next two to three years through workovers, infrastructure repairs and short-cycle upstream investments.

Rystad estimates that Venezuela currently produces 1.1 million bbl/d, meaning a 300,00 bbl/d increase would bring the total to 1.4 million bbl/d. The firm says this level would have a limited effect on global markets.

Long-Term Scenarios

Pushing production above 1.4 million bbl/d will be more difficult, Rystad assesses. However, the firm says Venezuela could reach 2 million bbl/d by the 2030s with an additional investment of $41 billion.

“Going beyond 2 million bbl/d in the 2030s will be even more challenging,” Rystad comments. “We estimate that a staggering $75 billion in additional investments is needed to bring production from 2 million bbl/d in the early 2030s to 3 million bbl/d in 2040.”

For that investment to materialize, oil prices may need to be higher than they are today. “With current technologies and service cost levels, around 60% of this investment, or $44 billion, is associated with projects requiring stable market conditions with oil prices above $80 per barrel,” Rystad explains.

“With the current global crude market fundamentals, resilient U.S. shale, ample spare OPEC capacity, and robust growth from Guyana and other regions, there is very little room for 2 million bbl/d of additional capacity from Venezuela until the second half of the 2030s,” it writes. “A more realistic 15-year ceiling for Venezuela’s oil supply probably lies in the 2-2.5 million bbl/d range, but potential remains for a longer-term 3 million bbl/d recovery.”

For more details on Rystad’s rationale, as well as the capital expenditures required for Venezuela to simply maintain its current production, see Venezuela’s Long Road Back: The Cost, Conditions and Timeline to 3 Million Bpd, which is part of Rystad’s “Trump and Energy” series.

For Goehring & Rozencwajg’s commentary, which includes more historical detail, see Venezuela's Crude Reality.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.