A New Dynamic

U.S. LNG Easing Russia’s Leverage Against Europe

By Del Torkelson

CEDAR CREEK, TX.–The United States’ forthcoming status as a net energy exporter turns the country’s central energy concern on its head, a geopolitical analyst assessed in late June. Moreover, suggested Anna Mikulska, nonresident fellow in energy studies at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, the ripples from U.S. energy exports are making waves across the globe that will only gain strength if the country makes some shrewd near-term moves.

“It is not about security of supply. As the United States becomes an energy exporter, there is more to be said about the issue of security of demand. Where are our exports going to go?” she posed. “U.S. demand is going to stay stable, whereas production is picking up. If the United States can achieve security of demand, it not only can improve the economy, but also can influence the world’s political direction.”

In her remarks at the Independent Petroleum Association of America’s midyear meeting, held June 25-26 at the Hyatt Regency Lost Pines Resort & Spa outside Austin, Tx., Mikulska–who also is a senior fellow at the University of Pennsylvania’s Kleinman Center for Energy Policy–made what she called a geo-economic case that it was in the United States’ economic and foreign policy interests to back European liquefied natural gas infrastructure.

“The United States can fund investment in natural gas infrastructure that will allow easy delivery of non-Russian resources to Europe,” she said. “A private company probably will not do that without specific economic benefits and will not be interested in the political benefits. How can policymakers incentivize these national-level decisions? We suggest the United States make a strategic investment in much more liberal and diversified markets for those that lack them.”

Petro-Carrots, Petro-Sticks

The proliferation of LNG is changing natural gas from a regional to an international commodity, Mikulska observed. Not long ago, she recalled, LNG consumption tended to be limited to countries for which pipeline connections were impossible, such as Japan and South Korea. However, that changed in the wake of the U.S. shale revolution and technology innovations that shrank liquefaction costs.

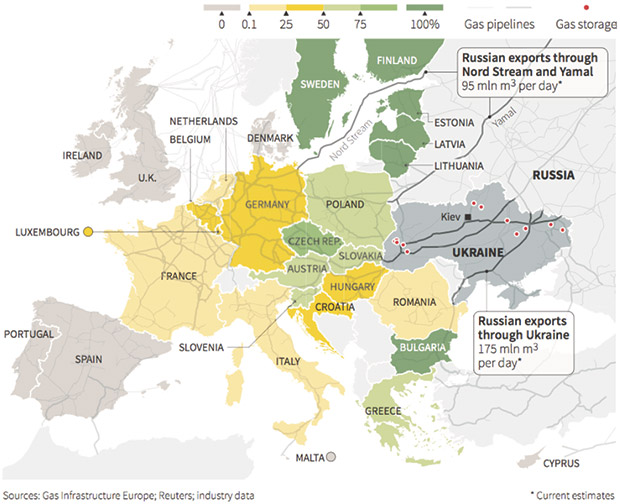

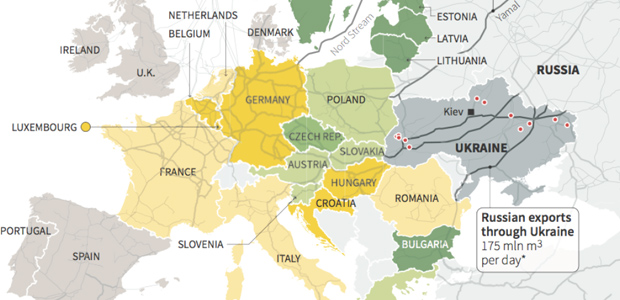

“The natural gas market has changed dramatically and is becoming more global and fungible–and the United States is a big part of this,” she stated. “This changes the geopolitical dynamics. That specifically goes for Europe, and very much so for the central and eastern parts, where the regional system has been based on pipeline delivery of Russian natural gas.”

Fungible supply makes a key difference, Mikulska maintained, pointing to Eastern Europe’s crude oil imports as an example.

“These countries are able to access oil through other suppliers,” she pointed out. “When Russia denied oil delivery because of political issues, it was not able to stand by this bargaining position because Poland and its neighbors simply would buy oil from other suppliers. That is not the case for natural gas.”

Already, Mikulska indicated, Europe is receiving 10 percent of U.S. LNG exports, diversifying a market long under Russia’s sway. “Russian energy policy has been very geopolitically oriented,” she characterized. “Russia has used petro-carrots and petro-sticks heavily throughout the decades within the markets that depend on its oil or gas. LNG . . . is changing perspectives for Russia and for Central and Eastern Europe.”

For Russia, that new perspective entails an effort to diversify pipeline avenues to prevent the country from being left with a large volume of stranded gas, she explained. Therefore, she noted, the country is in the advanced stages of building pipelines into China and Turkey, and is looking into collaborating with Saudi Arabia and the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries in hopes of possibly sending some of its gas there.

From East To West

According to Mikulska, the European Union has been working toward natural gas network integration, diversification and expansion, which includes engaging with other regions that can provide not only LNG but also pipeline gas. However, she described, a distinct rift separates the Western European perspective from that of Central and Eastern Europe.

“At the risk of making it too simplistic, Western Europe is not as concerned about diversifying its source,” she summarized. “Those countries often are seen as more concerned about diversifying the routes through which natural gas will come so that they will not be disturbed by–for example–a crisis in Ukraine, such as what happened following Russia’s invasion there. They are interested in whether they can bring Russian gas through other pipelines.”

Independent Petroleum Association of America Vice President of Economics and International Affairs Fred Lawrence chats with geopolitical energy expert Anna Mikulsa before her remarks at IPAA’s 2018 midyear meeting, held June 25-26 at the Hyatt Regency Lost Pines outside Austin, Tx. During her presentation, Mikulska indicated that eastern European countries merely needed the capability to import liquefied natural gas to help prevent Russia from misusing its energy exports to achieve political ends.

However, European countries’ views tend to shift with closer proximity to Russia, Mikulska indicated, a perspective largely based on history. Central and Eastern European countries often embrace decidedly pro-U.S. outlooks, she said, which often clash with Western European countries’ more convoluted attitudes toward the United States. However, she held, Russia’s shadow is not as dark in Western Europe. In contrast, she noted, Eastern and Central Europe have experienced what it is like to depend almost entirely on Russia for gas.

“Generally, Central and Eastern European countries that depend on Russian natural gas pay much more for it than countries that are less dependent, even when the transport and transit fees are much cheaper,” she illustrated. “Italy pays less than Poland, even though it probably should pay more because of transport costs. But Russia has no reason to decrease Poland’s price, since there is no competitor.

“There are different types of benefits and influence Russia can get out of being the sole and dominant supplier,” Mikulska continued. “Russia applied not only economic pressure, but also geopolitical pressure on the Ukraine. You can see price changes in the Ukraine that are quite distinct and correspond more with political dynamics than economics.”

Credible Threat

Adding U.S. LNG to the world market transforms the equation, Mikulska considered. She cited her Baker Institute colleague, Kenneth Medlock, as describing the mere possibility of U.S. LNG as a “credible threat” to Russian leverage.

“U.S. LNG does not even have to get there, but if it is an option to replace Russian gas, that tempers Russia’s ability to overprice it or use it for political goals. That introduces the United States as part of the geopolitically stabilizing force that can protect U.S. allies in Europe,” she said.

As for evidence that the threat of U.S. LNG is making a difference already, Mikulska pointed to research from Rice University doctoral student Nathalie Hinchey.

Since private companies are unlikely to fund natural gas infrastructure that will allow Europe to easily import non-Russian resources, the United States should make a strategic investment in such facilities, assesses global energy expert Anna Mikulska. A nonresident fellow in energy studies at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy and senior fellow at the University of Pennsylvania’s Kleinman Center for Energy Policy, Mikulska argued that the United States had a decided geopolitical interest in a diversified European energy market.

“Once Lithuania started to receive LNG through its new terminal, its natural gas prices dropped, including the prices it paid for Russian gas,” she detailed. “It does work. It makes Russia a normal gas supplier that has to compete and does not have much more power than anybody else.”

That harmonizes with the rest of the Baker Institute’s research, she held. “Liberalized market conditions greatly impede Russia’s ability to use geopolitical power in Europe, which indicates what U.S. policy toward liberalization and LNG markets should be,” Mikulska reasoned. “It is very important to make sure Eastern and Central Europe not only diversify their gas markets, but also make them more liquid.”

Therefore, she advised, U.S. policymakers should back the construction of LNG infrastructure in Central and Eastern Europe, even if there are no guarantees those countries ever will import large volumes of U.S. gas. With a variety of options, those countries are likely to import some U.S. gas, but the central consideration is that they become possible outlets for it–which will help U.S. economic and foreign policy interests.

“It is a short-term investment with long-term benefits,” she concluded. “Infrastructure is going to stay there, it is going to support the market and equalize it. A push to liberalize the market will help. It bolsters European resilience and impacts the Russian economy, since Russia still will sell the gas, but at a much lower price.”

For more coverage of IPAA’s midyear meeting, see AOGR’s August issue.

For other great articles about exploration, drilling, completions and production, subscribe to The American Oil & Gas Reporter and bookmark www.aogr.com.